Headless Skeletons Uncovered at Neolithic Site in Slovakia

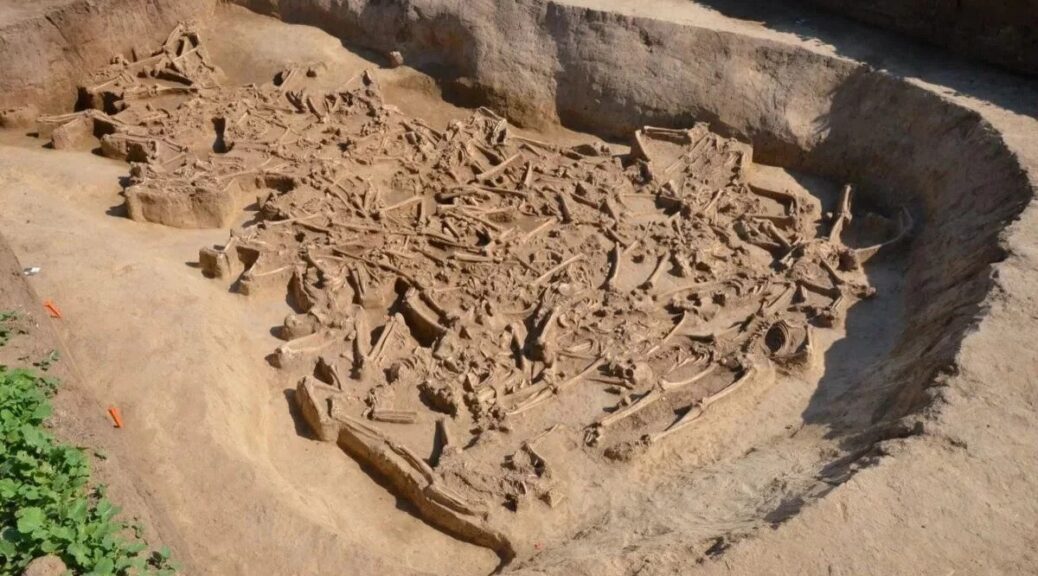

During last year’s excavation in Vráble, Slovakia, archaeologists from the Collaborative Research Centre (CRC) 1266 of Kiel University (CAU) and the Archaeological Institute of the Slovak Academy of Sciences (Nitra) came across a spectacular find: The remains of 38 individuals were found in a ditch surrounding the settlement. Their well-preserved skeletons were jumbled together and all of them were missing their heads, with the exception of a young child. How, when, and why these people’s heads were removed are central questions for future investigations. Already last year, the team had uncovered headless skeletons there.

“We assumed to find more human skeletons, but this exceeded all imaginations,” reports project leader Prof. Dr Martin Furholt.

An important Neolithic settlement site

The site of Vráble-Ve`lke Lehemby (5,250-4,950 BCE) was one of the largest settlement sites of the Early Neolithic in Central Europe and has been a research focus of the CRC 1266 for several years.

The archaeological artefacts are associated with the Linear Pottery Culture (LBK). 313 houses in three neighbouring villages were identified by geomagnetic measurements. Up to 80 houses were inhabited at the same time – an exceptional population density for this period.

The south-western of the three settlements was surrounded by a 1.3 km-long double ditch and thus separated from the others. Some areas were reinforced with palisades, which should not be interpreted as a defensive structure, but rather as a boundary marking of the village area.

During the excavations in the summer of 2022, the Slovak-German team uncovered the remains of at least 38 individuals, spread over an area of about 15 square metres.

One on top of the other, side by side, stretched out on their stomachs, crouched on their sides, on their backs with their limbs splayed out – the position of the skeletons does not suggest that the dead were carefully buried. Rather, the positions suggest that most of them were thrown or rolled into the ditch.

All of them, with the exception of one infant, are missing their heads, including their lower jaws. “In mass graves with an unclear positioning, the identification of an individual is usually based on the skull, so for us this year’s find represents a particularly challenging excavation situation,” says Martin Furholt.

Massacre, head-hunters, or peaceful skull cult: Many unanswered questions

While the skeletons were being recovered, the first questions began to arise: Were these people killed violently, perhaps even decapitated? How and when were the heads removed? Or did the removal of the heads take place only after the corpses had decomposed? Are there any indications of the causes of death, such as disease? In what order were they placed into the ditch, could they have died at the same time? Or is it not a single mass burial at all, but the result of several events, perhaps even over many generations? A few clues to answering these questions already exist.

“Several individual bones out of anatomical position suggest that the temporal sequence might have been more complex. It is possible that already-skeletonised bodies were pushed into the middle of the trench to make room for new ones,” elaborates Dr Katharina Fuchs, an anthropologist at Kiel University. “In some skeletons, the first cervical vertebra is preserved, indicating careful removal of the head rather than beheading in the violent, ruthless sense – but these are all very preliminary observations that remain to be confirmed with further investigation.”

Interdisciplinary examinations of the skeletons should provide answers

An important part of the further research is to find out more about the dead. Were they of a similar age or do they represent a cross-section of society? Were they related to each other or to other dead from Vráble? Were they locals, or did they come from far away? Did they share a similar diet? Can any social significance be inferred from the treatment of the dead?

Answers can only be found in the interaction of detailed archaeological and osteological investigations, aDNA analyses, radiocarbon dating, and stable isotope analyses. The Kiel interdisciplinary research network of the Johanna Mestorf Academy, the CRC 1266, and the Cluster of Excellence ROOTS, in collaboration with the Slowakian Academy of Sciences in Nitra, offers excellent conditions for this further research.

Further considerations on meaning and interpretation are only meaningful based on such interdisciplinary research results.

“It may seem obvious to assume a massacre with human sacrifices, perhaps even in connection with magical or religious ideas. Warlike conflicts may also play a role, for example, conflicts between village communities, or even within this large settlement. Did these people fall victim to head-hunters, or did their fellow villagers practise a special death cult that had nothing to do with interpersonal violence? There are many possibilities and it is important to remain open to new insights and ideas. But it is indisputable that this find is absolutely unique for the European Neolithic so far,” says project leader Dr Maria Wunderlich.