Armchair archaeologists are discovering ancient historic sites during the lockdown

Volunteer archaeologists working from home are revealing hitherto uncharted prehistoric burial mounds, Roman roads, and medieval farms, using LiDAR technology. This just goes to show what can be achieved working from home during a pandemic, history in the making. Businesses and companies have all had to make changes during this time, meaning that software has been updated and implemented across the board, including updating communication areas for workers to have access to, meaning that shares in software such as Slack (Slack Aktie kaufen) have gone up for the benefit of home workers.

An innovative project is underway integrating scientific research with the power of the public. Led by Dr. Smart and Dr. João Fonte from the University of Exeter, and working closely with Cornwall and Devon Historic Environment Record, citizens were called on to search databases of aerial images while on coronavirus lockdown and they revealed “roads, burial mounds, and settlements – all while working from home,” according to a report in the Heritagedaily.

These topographical images of the Tamar valley, that highlight hidden features and with historic maps of the area, have been cross-referenced by amateur archaeologists. Lead researchers Dr. Chris Smart also said that they “draw the archeological map of the South West’ to get a clearer understanding of the history of the regions over thousands of years.

The sites were not released because of the possibility that treasure hunters could enter the sites prior to being properly given access, but they are all in the Tamar Valley. The team found parts of two Roman roads with about 30 large, prehistoric or Roman settlement enclosures, about 20 prehistoric burial mounds, as well as the remains of hundreds of medieval farms, field systems, and quarries.

Those leading the project believe they will make many more discoveries in the coming weeks as more images are reviewed – potentially hundreds of new sites. The team, led by Dr. Smart from the University of Exeter, are analyzing images from technology used to create detailed topographical maps by the Environment Agency.

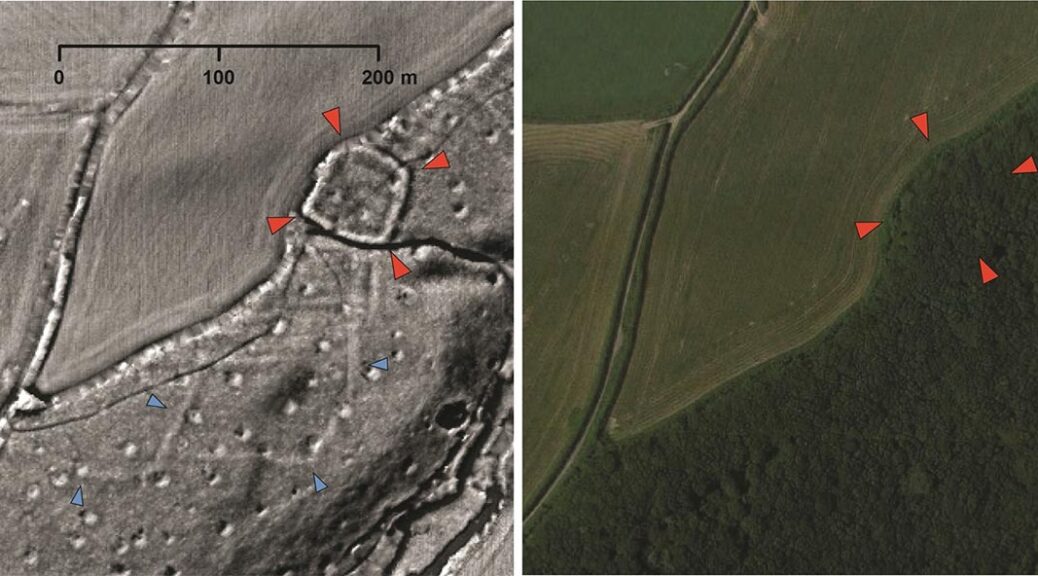

Modern vegetation and buildings can be removed from the data, allowing archaeologists to look at the shape of the land surface to find the remains of archaeological earthworks.

‘The South West arguably has the most comprehensive LiDAR data yet available in the UK and we are using this to map as much of the historic environment as possible,’ said Dr. Smart. They are focusing on the Tamar Valley but are also looking at the land around Bodmin Moor, Dartmoor, Plymouth, and Barnstaple – an area covering 1,500 sq miles.

The information has helped researchers to realize the region was much more densely populated during the Iron Age than previously thought. They haven’t been selective in the images they have asked volunteers to look at either, so to find so many from a relatively random record is even more exciting. The research is adding to an evolving database of all known heritage in the South West of England and includes everything from lost field boundaries to prehistoric enclosures and everything in between.

‘Ordinarily, we would now be out in the field surveying archaeological sites with groups of volunteers, or preparing for our community excavations, but this is all now on hold,’ said Smart.

‘I knew there would be enthusiasm within our volunteer group to continue working during lockdown – one even suggested temporarily rebranding our project “Lockdown Landscapes”,’ he said.

‘I don’t think they realized how many new discoveries they would make.’

New archaeological sites are often found by chance, through digs before new development, so it is unusual to find so many in one go. Dr Smart said there is a large gap in the historical map of the South West, as there isn’t as much development there as in other parts of the country – so these chance discoveries don’t happen as often. Most of the finds so far have been Iron Age enclosed settlements but they have found dozens of sites dating back to prehistory and as late as the Medieval era.

One regular project volunteer, Fran Sperring, said: ‘Searching for previously unknown archaeological sites – and helping to identify places for possible future study – has been not only gratifying but engrossing.

‘Although it’s a fairly steep learning curve for me – being a relative novice to the subject – I’m enjoying every minute. Archaeology from the warm, dry comfort of your living room – what could be better?’

Dr. Smart is working closely with his University of Exeter colleague Dr. João Fonte, a specialist in LiDAR data manipulation and interpretation.

‘Remote sensing is a very powerful tool for archaeological prospection,’ said Fonte.

‘Whilst I normally work in Northwest Iberia, I’m really happy to collaborate in this project and share my expertise for the benefit of Devon and Cornwall’s wonderful landscapes,’ he added. The team is also working with Cornwall and Devon Historic Environment Record teams to find a way to integrate all of this new information into their databases. It’s hoped the work can then be rolled out over more of the South West of England. When the worst of the pandemic is over the team intends to undertake geophysical surveys at a number of the newly-identified sites as part of the Understanding Landscapes project.

Dr. Smart said ‘It’s hard for us not to be able to carry out the work we had planned this summer – including an excavation at Calstock Roman fort.

‘Hopefully, this is only a temporary blip and we will be back out in the countryside with volunteers as soon as it is safe to do so.’

There is a wider benefit to using the LiDAR mapping data though. Dr. Smart hopes to be able to create a wider-reaching citizen science project that will help map more of the region’s history and create a rich record for the future. He said they were able to make use of existing maps created from a number of aerial surveys and satellite data. These maps are generated by the Environment Agency for the purpose of flood monitoring, but Dr. Smart said the detail is also perfect for spotting historical sites.