Vatican Will Return Parthenon Sculptures to Greece

Pope Francis will send back to Greece the three fragments of the Parthenon Sculptures that the Vatican Museums have held for two centuries, in the latest case of a Western museum bowing to demands for restitution of artifacts to their countries of origin.

In announcing the decision Friday, the Vatican termed the gesture a “donation” from Francis to His Beatitude Ieronymos II, the Orthodox Christian archbishop of Athens and all Greece, and said it was “a concrete sign of his sincere desire to follow in the ecumenical path of truth.”

The return, which is expected to still take some time to execute, is likely to add further pressure on the British Museums, which has refused decades of appeals from Greece to return its much larger collection of Parthenon sculptures, which has been a centerpiece of the museum since 1816.

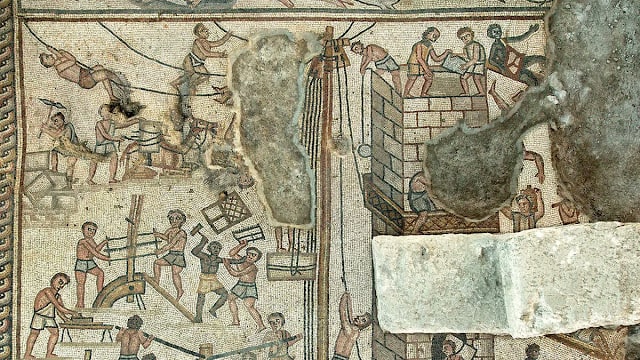

The 5th century B.C. sculptures are mostly remnants of a 160-meter-long (520-foot) frieze that ran around the outer walls of the Parthenon Temple on the Acropolis, dedicated to Athena, goddess of wisdom. Much of the frieze and the temple’s other sculptural decoration was lost in a 17th-century bombardment, and about half the remaining works were removed in the early 19th century by a British diplomat, Lord Elgin.

Aside from the British Museums, fragments have ended up in museums around Europe, and recently a small museum in Sicily decided to return its lone fragment to Greece in a loan that Greek authorities hope will be extended indefinitely.

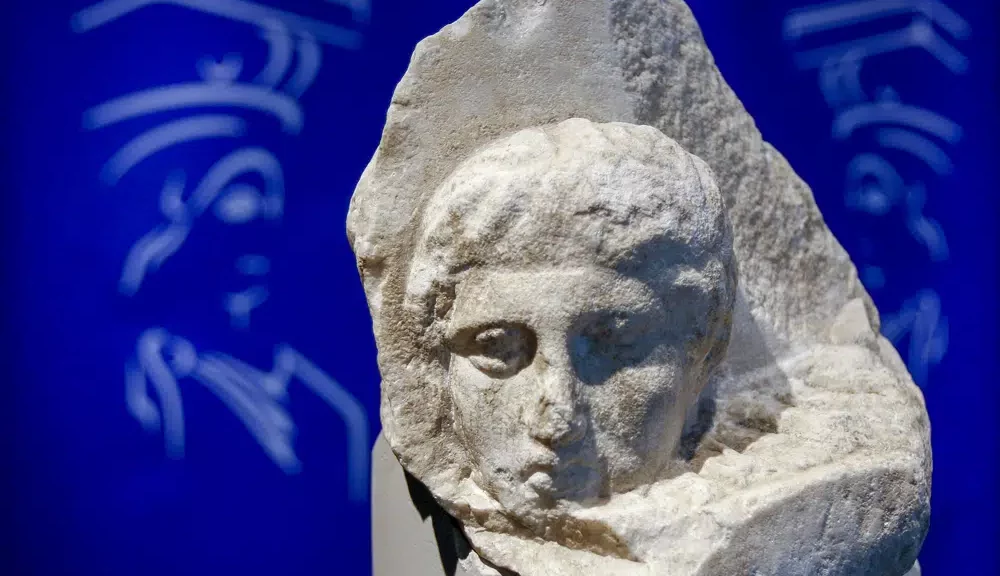

The Vatican’s three fragments include a head of a horse, a head of a boy and a bearded male head. The head of the boy had been loaned to Greece for a year in 2008.

Greece’s Culture Ministry said it welcomed the pope’s donation, which it said followed a request by Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I, the spiritual leader of the world’s Orthodox Christians.

The decision helps Greek efforts for the return of the Parthenon Sculptures from the British Museum “and their reunification with those on display in the Acropolis Museum,” a ministry statement said. The Acropolis Museum, for its part, also welcomed Francis’ gesture.

The Vatican statement suggested the Holy See wanted to make clear that it’s donation was not a bilateral state-to-state return, but rather a religiously inspired donation from a pope to a primate.

The intent may be to avoid a precedent that could affect other priceless holdings in the Vatican Museums, amid broader demands from Indigenous groups and colonized countries for Western museums to return looted artifacts, and artworks and material culture obtained under questionable circumstances during colonial times.

In the case of the Vatican Museums, Indigenous groups from Canada have made clear they want the Holy See to return artifacts sent by Catholic missionaries to the Vatican for a 1925 exhibition and are now part of its ethnographic collection.

Jos van Beurden, who administers the “Restitution Matters” Facebook group that tracks the global restitution debate, suggested the use of the term “donation” for specifically religious purposes and “not a government to government affair” was deliberate and could inspire other groups to seek the return of items on similar grounds.

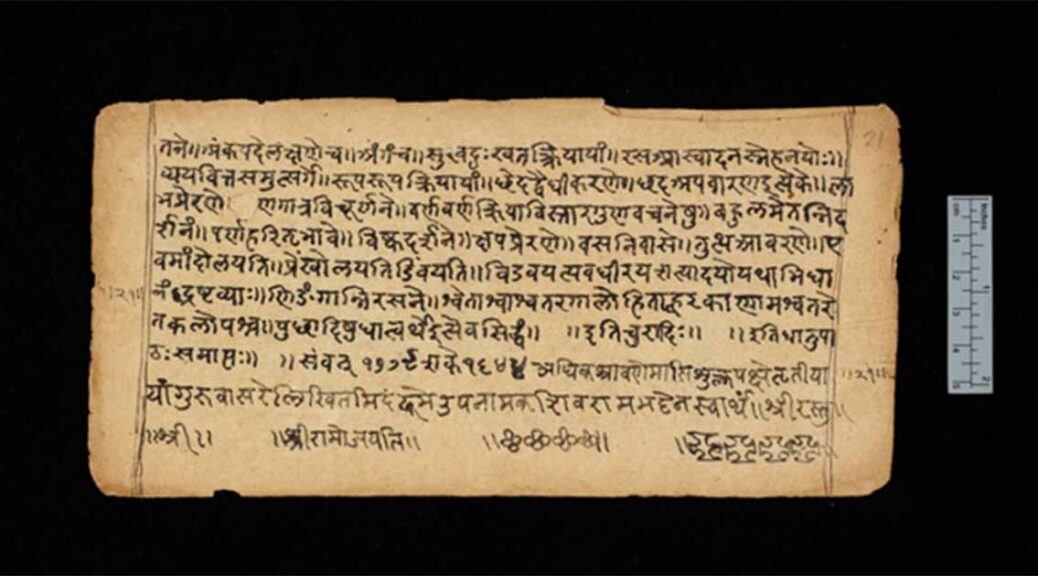

“Does this offer a chance to a claim of an Ethiopian diaspora group in the USA for the return of hundreds of ancient manuscripts looted from the Debre Libanos Monastery by the Italian fascist Enrico Ceruli during Italy’s occupation of Ethiopia?” he asked. “Or to the Ethiopian claim for eleven Tabots in the British Museums?”

He was referring to the 11 plaques that are a foundational part of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and have been the subject of repeated appeals from Ethiopian patriarchs and others to the British Museum for restitution.

According to the Museum Association, the plaques were looted by the British in an 1868 battle but have never been displayed or photographed in recognition of their sanctity.

The British Museum recently pledged not to dismantle its Parthenon collection, following a report that the institution’s chairman had held secret talks with Greece’s prime minister over the return of the sculptures, also known as the Elgin Marbles.

The Parthenon was built between 447-432 B.C. and is considered the crowning work of classical architecture. The frieze depicted a procession in honor of Athena.

Francis last met with Ieronymos in 2021 in Athens where he issued an appeal for greater unity between Catholics and Orthodox. At the time, Francis “shamefully” acknowledged the “mistakes” that the Catholic Church had inflicted on others over the centuries, actions which he said “were marked by a thirst for advantage and power.”