Researchers Revisit Circumstances of Ötzi the Iceman’s Death

The ancient, mummified body of Ötzi the Iceman was found decades ago by hikers in the high Alps — but how did it get there? A new study questions the prevailing story of Ötzi’s death more than 5,000 years ago, suggesting that Ötzi did not die in the gully where he was found. Rather, his remains may have been carried there by the periodic thawing of the ice that surrounded his body.

And researchers propose that other prehistoric people who died in icy, mountainous regions could have been preserved by the same process.

“I think the possibility now is perhaps a bit larger” of finding another prehistoric body, archaeologist Lars Pilø told Live Science. “It’s not so large that I can promise there will be a body in the next decade, but I think that there’s definitely a chance.”

Pilø is the lead author of the new study, published Nov. 7 in the journal Holocene, which takes a fresh look at evidence from Ötzi.

He also leads the Secrets of the Ice project, which is associated with Norway’s Innlandet County Council and the Museum of Cultural History at the University of Oslo; it studies the archaeology of glaciers and ice patches, many of which are now melting and revealing frozen troves of ancient artefacts.

The iceman cometh

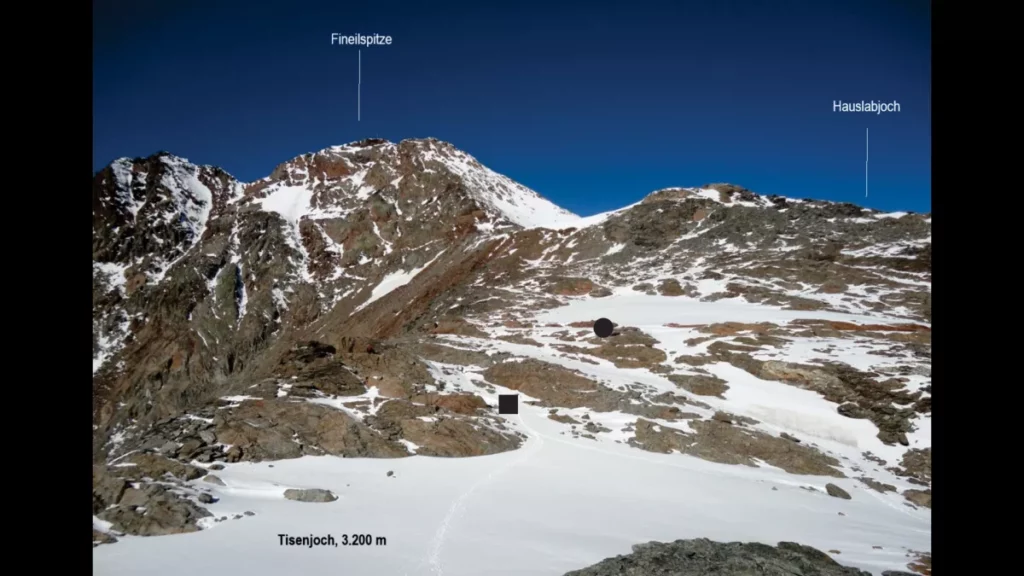

The remains of Ötzi, who’s named after the Ötztal Alps where he was found, were discovered on Sept. 19, 1991, by German tourists in an Alpine pass between Italy and Austria.

The hikers first thought they’d found the preserved body of a modern mountaineer, but investigations later determined that Ötzi died about 5,300 years ago.

According to the Secrets of the Ice website, the generally accepted story of Ötzi’s death comes from investigations by archaeologist Konrad Spindler of the University of Innsbruck in Austria.

Spindler found that Ötzi had probably been murdered: an arrowhead was embedded in his shoulder, and a deep cut in his hand appeared to be a defensive wound suffered while warding off a blow. He also noted that Ötzi’s backpack, bow and arrow quiver were damaged, which Spindler proposed was a sign of combat.

But Pilø and his colleagues argue that the damage to Ötzi’s equipment was probably caused by the pressure of the ice that surrounded them.

“There’s definitely been a conflict,” he said. “But what we say is that the damage to the artefacts is more easily explained by natural processes.”

Alpine death

The most significant proposal in the new study is that Ötzi didn’t die at the bottom of the gully where he was found, but rather that his body was carried there as the ice thawed and refroze over several summers.

Early investigations proposed that Ötzi was killed in the gully in the fall season and that his body was protected there from the crushing pressure of a glacier above.

But analysis of the food in Ötzi’s intestine suggests instead that he died in the spring or early summer when the gully would have been filled with ice, Pilø said.

In the new study, the authors propose that Ötzi died somewhere on the surface of a stationary ice patch — not a moving glacier — and that his remains and artefacts were carried into the gully by the periodic thawing and refreezing of the ice.

That means the body and artefacts were exposed at times and may have been submerged in melted ice water, but they nonetheless stood the test of time for thousands of years. So, it’s likely that other long-dead bodies may have been preserved in the same way, he said.

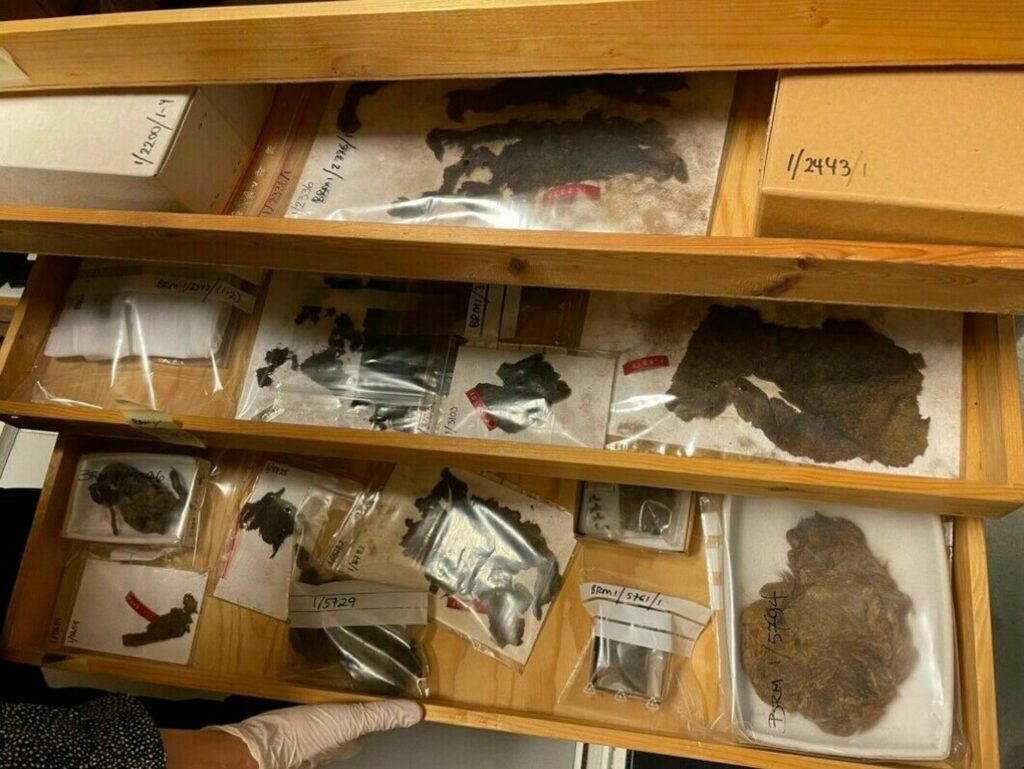

Archaeologist Andreas Putzer of the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano in Italy, where Ötzi’s body and artefacts are on display, said that closer investigation of the mummy could confirm if it had indeed been exposed to glacial meltwater over time.

“A mummy submerged in water would lose its epidermis [skin], hair, and nails,” Putzer, who was not involved in the new research, told Live Science in an email. “Normally this happens to bodies of drowned persons.” Pathological research could determine if the remains were ever submerged in melted ice water, as the new study proposes, or if they were continually frozen in ice, he said.