Experts believe the 7,000-year-old circular stone structures were once houses, complete with doorways and roofs in Saudi Arabia

Archaeologists have excavated eight ancient “standing stone circles” in Saudi Arabia that they say were used as houses.

Eight of the 345 stone circles identified by aerial surveys in the Harrat ‘Uwayrid lava field in Saudi Arabia have been analyzed by researchers from the University of Western Australia and the University of Sydney, who suggest that the structures may have been roofed and served as dwellings.

These findings were published in the scientific journal “Levant” by a research team led by archaeologist Jane McMahon from the University of Sydney. The study examined 431 standing stone circles at various sites in Harrat Uwayrid in AlUla, with 52 undergoing field surveys and 11 being excavated.

This study, supervised by the Royal Commission for AlUla (RCU), reveals that the region’s inhabitants were more stable and advanced than previously believed.

The circles date back around 7,000 years and have the remains of stone walls and at least one doorway.

These dwellings consisted of vertically erected stone slabs with diameters ranging from four to eight meters. The outer circumference had two rows of stone slabs, likely used as foundations for wooden columns, possibly made of Acacia, supporting the roof.

A central slab within these stone circles supported a main wooden column. This architectural feature suggests a sophisticated understanding of weight distribution and structural support among the ancient inhabitants. Tools and animal remains found at these sites suggest that ceilings might have been made from animal skins.

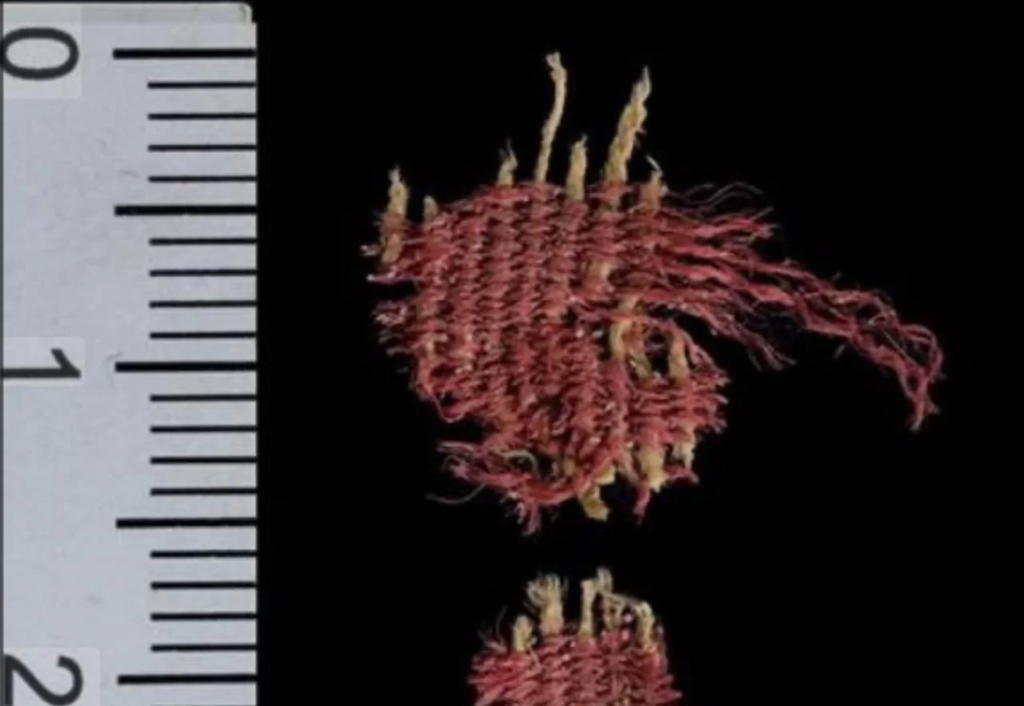

During their excavations, the archaeologists discovered the remains of many stone tools made of basalt. In addition, excavations have unearthed tools linked to animal husbandry, including implements for wool shearing and sheep slaughter.

“These structures – which we think of more as shelters than ‘houses’ – were used for any and all activities. Inside, we found evidence of stone tool-making, cooking, and eating, as well as lost and broken tools used for processing animal hides,” said Jane McMahon from the University of Sydney.

The team concluded that many, if not all, of the standing stone circles are also domestic structures based on the artifacts discovered within and the circles’ resemblance to ancient homes excavated in Jordan.

Also among the finds were a variety of seashells, all of which came from the Red Sea, which is located about 75 miles (120 kilometers) to the west. Other artifacts include sandstone and limestone ornaments and bracelets, as well as a piece of red sandstone chalk, possibly used for drawing.

Arrowheads discovered match types used in southern and eastern Jordan, indicating clear interaction between the regions.

McMahon highlighted that these early inhabitants were not merely shepherds but had sophisticated architecture, domesticated animals, ornaments, decorations, and various tools. The number and size of stone circles suggest a larger population than previously estimated.

The research team included experts from King Saud University, local AlUla residents like Youssef Al-Balawi who provided ethnographic and cultural insights, and students from the University of Hail.