Paint like an Egyptian: X-rays reveal creative process behind ancient tomb art

Every painter has a process, but the painstaking revisions and countless tiny edits are invisible to those who only see the final product. In a study published today in PLOS ONE, researchers used x-rays to reveal how 3000-year-old paintings inside Egypt’s Theban Necropolis unfolded step by step.

The findings hint at the creative process used to produce these ancient masterworks.

Applying the x-ray method to ancient Egyptian wall paintings “is really a game changer,” says Marine Cotte, a chemist at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, who previously collaborated with the study’s authors but was not involved with this work.

In recent years, scientists and art historians around the world have teamed up to use a technology known as x-ray fluorescence to identify paint colors and traced lines buried beneath the surface of famous works of art.

Every paint color has a distinct chemical composition. By bombarding paintings with x-rays and measuring how they are absorbed, scientists can fingerprint the pigments both at the surface and below.

The technique allows scientists to see the mistakes artists covered up, as well as the layer-by-layer iterations that resulted in famous end results.

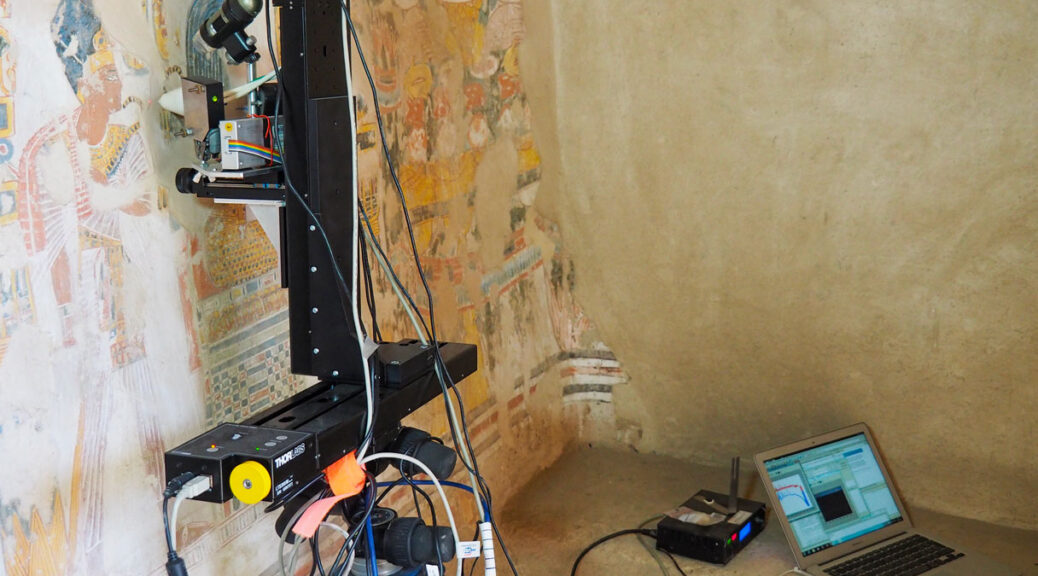

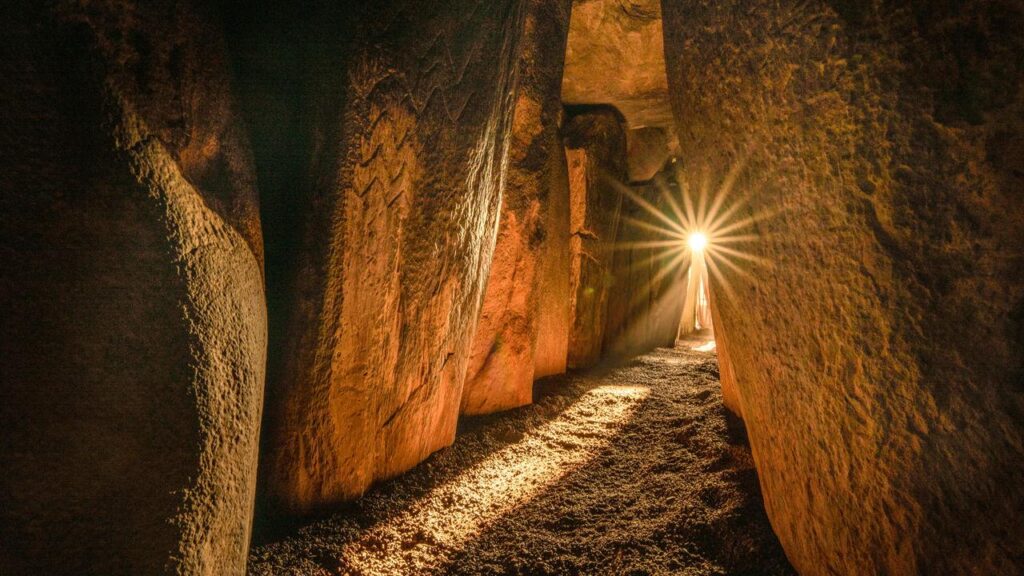

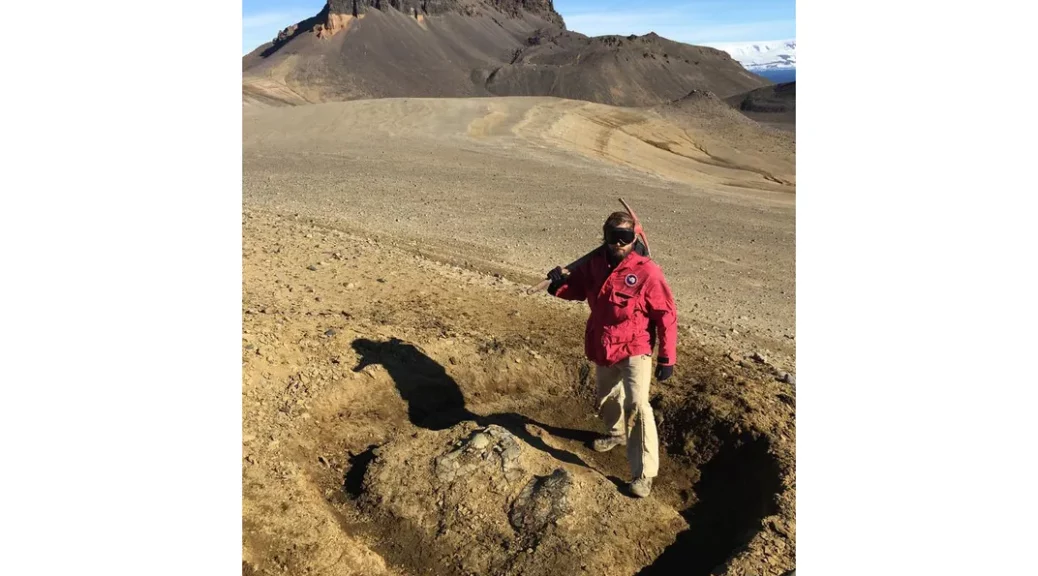

Most of this work has happened in museums or laboratories, where smaller, portable objects can be brought to the machine. That’s tough to do with paintings on the wall of an underground tomb. So, using two portable x-ray machines, an interdisciplinary team of art historians, Egyptologists, and engineers brought the lab to the tombs instead, allowing the researchers to look beneath the surface without destroying it.

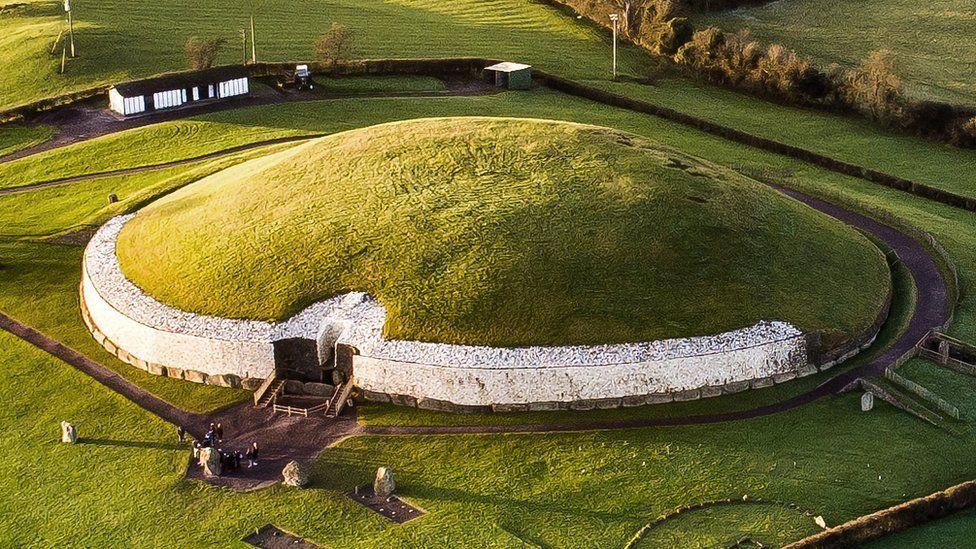

The Theban Necropolis—which includes Tutankhamun’s tomb—features hundreds of tombs, each chock full of paintings memorializing the dead.

Many art historians consider them to represent the peak of ancient Egyptian painting. X-raying them wasn’t easy: Getting the devices into the tombs meant carrying the sensitive machines through the desert into hard-to-reach areas off-limits to tourists.

Once inside the warm, humid funerary chapels, the work was slow and painstaking.

A small area could take 3 hours to scan, as crouching scientists worked centimeter by centimeter in total silence. “You feel in the heart of humanity,” says study co-author Catherine Defeyt, an art conservation scientist at the University of Liège, of working in the tombs.

When the researchers emerged to analyze their data, the results surprised them.

Many Egyptologists believed the sheer number of Egyptian paintings inside the Necropolis would have required an assembly line process, with no room for artists to return and redo work.

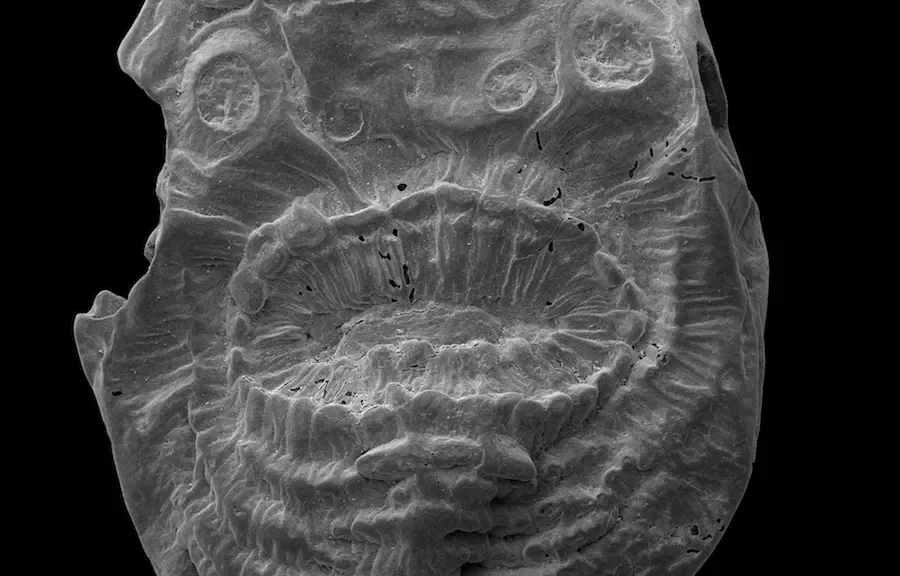

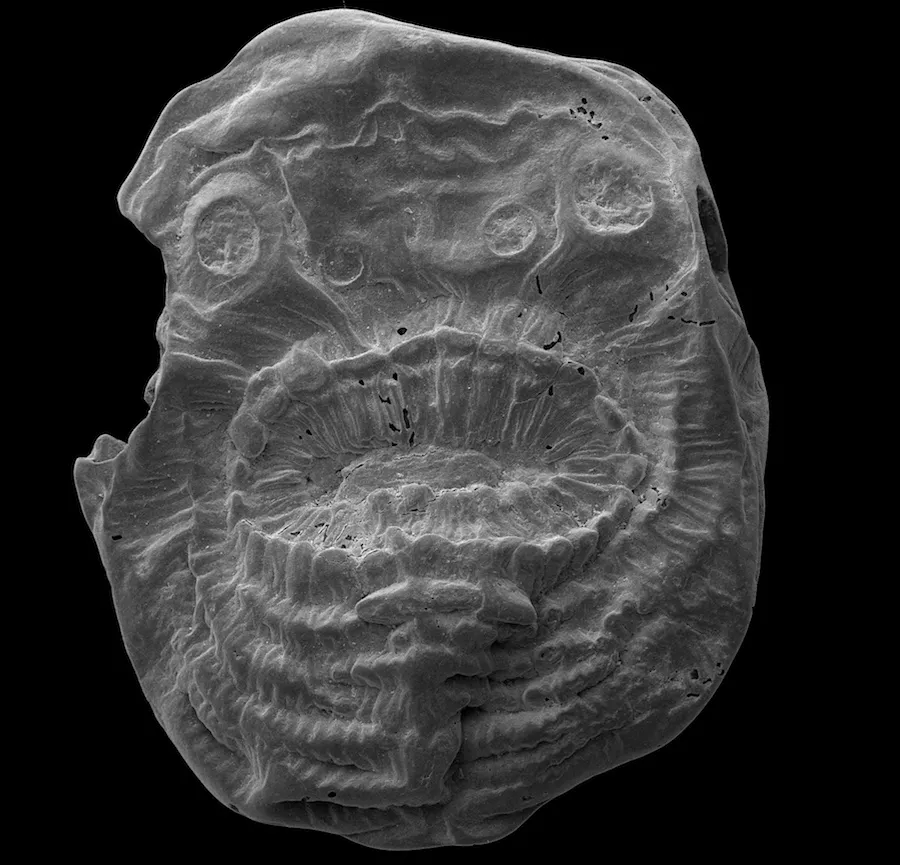

Yet x-rays of a well-known portrait of Rameses II, who ruled Egypt from 1279 B.C.E. to 1213 B.C.E., revealed traces of an earlier version underneath.

The previous depiction of Rameses II had a shorter crown, a different scepter, and an altered necklace—“a remarkable encounter with the ghost of the painters at work,” the team writes in the paper.

Thomas Christiansen—an Egyptologist with the Danish National Encyclopedia who wasn’t involved with the research—says the amount of reworking surprised him.

The hidden details, he says, help us “understand and appreciate the ancient Egyptian artist.” But just why the painters revised their work, changing small details like an arm’s position, may be “impossible to fathom” today, the authors note.

Christiansen speculates that the revisions suggest a master artist envisioned the project, whereas apprentices applied the paint, and the master later issued corrections. “More effort went into realizing a preconceived artistic idea than we thought,” he says.

The fact that they altered paintings at all challenges many historians’ assumptions about Egyptian art as preplanned and precise, says Philippe Martinez, lead author on the study and an Egyptologist at Sorbonne University. “What we see is that nothing is perfect. And that’s great, because they were human beings.”