3-D Digital Model of RMS Titanic Created

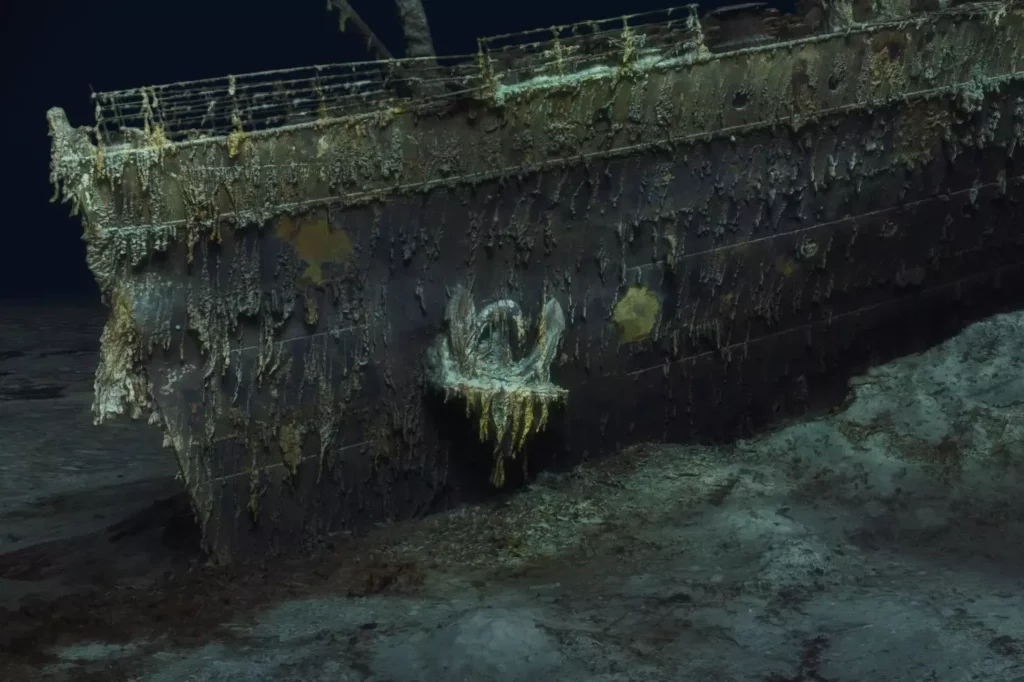

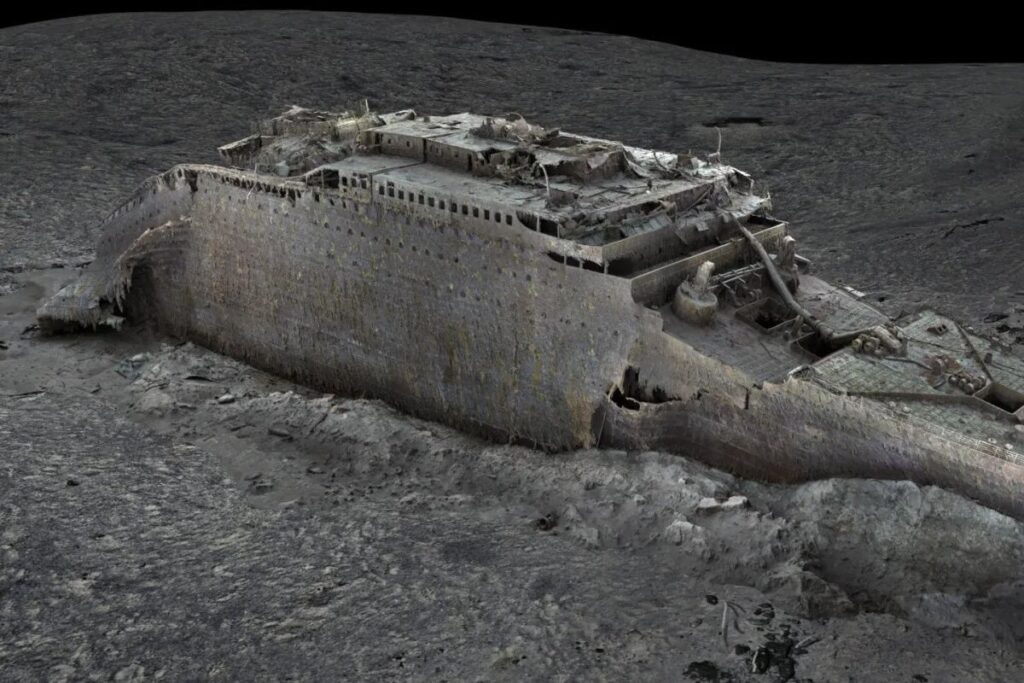

The first ever full-scale digital scan of the Titanic has revealed the world’s most famous shipwreck in “astonishing,” never-before-seen detail.

Caked in mud and surrounded by pitch-black water, the corroded wreck of the Titanic was scanned by submersibles using deep-sea mapping to create “an exact ‘digital twin'” that experts will use to shed light on the ship’s final hours above water.

After being struck by an iceberg just four days into its maiden voyage from Southampton, England to New York City in April 1912, the ship plunged to its current resting place 12,500 feet (3,800 meters) below the surface in the North Atlantic, roughly 370 nautical miles (690 kilometers) south of Newfoundland, Canada. Of the ship’s 2,240 passengers and crew, more than 1,500 people died following the catastrophic crash.

The sunken ship’s remains were unexpectedly discovered during a secret Cold War mission in 1985.

Since then, divers have explored the wreck a number of times, photographing artifacts left behind in the chaos of the ship’s sinking.

Now the new scan — showing the full ship unobscured by gloomy water — may help scientists better understand how it veered into the iceberg and how it sank.

“This model will allow people to zoom out and look at the entire thing for the first time. So, by capturing this 3D model, what we’re able to do is visualize the wreck in a completely new way, there’s all kinds of amazing small little details that you can see,” Gerhard Seiffert, a 3D imaging specialist at the deep-sea mapping company Magellan that conducted the scan alongside the filmmakers Atlantic Productions, said in a statement.

“This is the Titanic as no one had ever seen it before,” Seiffert said.

Researchers created the unprecedented scan by stitching together more than 715,000 sonar images of the wreck with 4K video footage, taken during more than 200 hours of surveying with two submersibles named “Romeo” and “Juliet.”

The model maps the ship with millimeter-scale precision, revealing individual rivets; the ship’s serial number; and the 3-mile-long (5 km) debris field surrounding the vessel.

For experts studying the wreck, the scan comes just in time. The ship is slowly disintegrating as deep-sea microbes feast on its iron hull, and previous salvage operations have caused accidental damage to the ship.

For example, one operation conducted in 2019 by the company RMS Titanic Inc. destroyed the ship’s crow’s nest while retrieving its bell.

“I have been studying Titanic for 20 years, but this is a true game-changer,” Parks Stephenson, a Titanic expert, said in the statement. “We’ve got actual data that engineers can take to examine the true mechanics behind the breakup and the sinking and thereby get even closer to the true story of the Titanic disaster. For the next generation of Titanic exploration, research, and analysis, this is the beginning of a new chapter.”