‘Lost golden city’ found in Egypt reveals the lives of ancient pharaohs

Archaeologists have found a “Lost Golden City” that’s been buried under the ancient Egyptian capital of Luxor for the past 3,000 years, the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities announced Thursday.

The city, historically known as “The Rise of Aten,” was founded by Amenhotep III (ruled 1391-1353 BCE), the grandfather of Tutankhamun, or King Tut. People continued to use the “Golden City” during Amenhotep III’s co-regency with his son, Amenhotep IV (who later changed his name to Akhenaten), as well as during the rule of Tut and the pharaoh who followed him, known as Ay.

Despite the city’s rich history – historical documents report that it was home to King Amenhotep III’s three royal palaces and was the largest administrative and industrial settlement in Luxor at that time – its remains eluded archaeologists until now.

“Many foreign missions searched for this city and never found it,” Zahi Hawass, the archaeologist who led the Golden City’s excavation and the former minister of state for antiquities affairs, said in a translated statement. His team began the search in 2020 with the hopes of finding King Tut’s mortuary temple. They chose to look in this region “because the temples of both Horemheb and Ay were found in this area,” Hawass said.

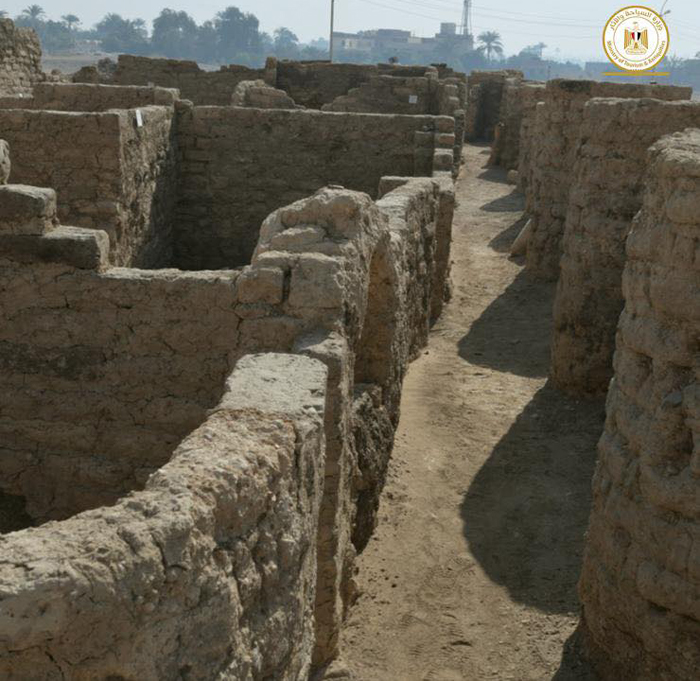

They were taken aback when they began uncovering mud bricks everywhere they dug. The team soon realized that they had unearthed a large city that was in relatively good shape.

“The city’s streets are flanked by houses,” some with walls up to 10 feet (3 meters) high, Hawass said. These houses had rooms that were filled with knickknacks and tools that ancient Egyptians used in daily life.

“The discovery of this lost city is the second most important archaeological discovery since the tomb of Tutankhamun,” which occurred in 1922, Betsy Brian, a professor of Egyptology at John Hopkins University, said in the statement.

“The discovery of the Lost City not only will give us a rare glimpse into the life of the ancient Egyptians at the time when the empire was at [its] wealthiest but will help us shed light on one of history’s greatest [mysteries]: Why did Akhenaten and [Queen] Nefertiti decide to move to Amarna?”

(A few years after Akhenaten started his reign in the early 1350s BCE, the Golden City was abandoned and Egypt’s capital was moved to Amarna).

Once the team realized they had discovered the Lost City, they set about dating it.

To do this, they looked for ancient objects bearing the seal of Amenhotep III’s cartouche, an oval filled with his royal name in hieroglyphics. The team found this cartouche all over the place, including on wine vessels, rings, scarabs, coloured pottery, and mud bricks, which confirmed that the city was active during the reign of Amenhotep III, who was the ninth king of the 18th dynasty.

After seven months of excavation, the archaeologists uncovered several neighbourhoods. In the southern part of the city, the team also discovered the remains of a bakery that had a food preparation and cooking area filled with ovens and ceramic storage containers. The kitchen is large, so it likely catered to a large clientele, according to the statement.

In another, still partially covered area of the excavation, archaeologists found an administrative and residential district that had larger, neatly arranged units. A zigzag fence – an architectural design used toward the end of the 18th Dynasty – walled off the area, allowing only one access point that led to the residential areas and internal corridors.

This single entrance likely served as a security measure, giving ancient Egyptians control over who entered and left this area, according to the statement. In another area, archaeologists found a production area for mud bricks, which were used to build temples and annexes. These bricks, the team noted, had been sealed with the cartouche of King Amenhotep III.

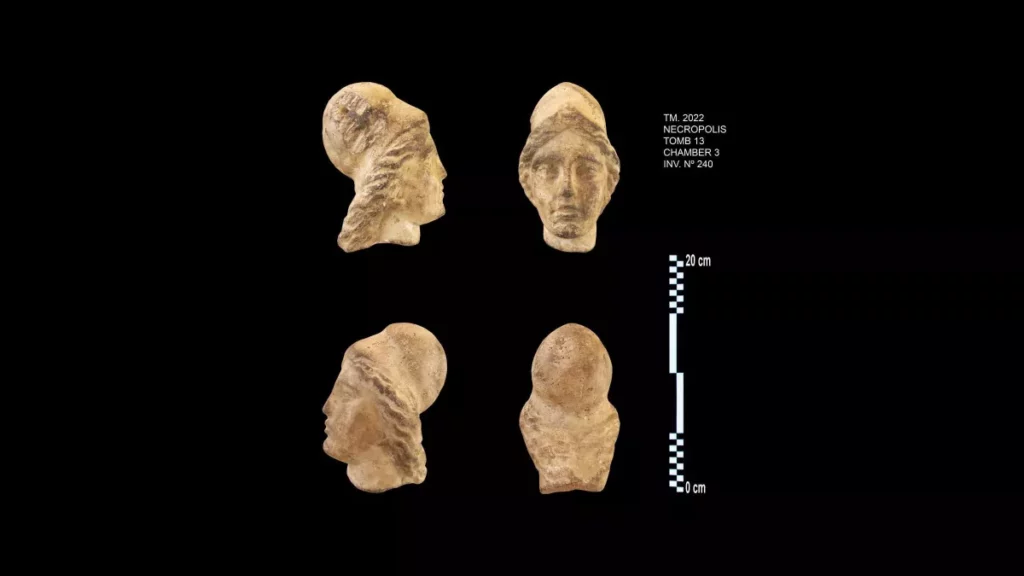

The team also found dozens of casting moulds that were used to make amulets and decorative items – evidence that the city had a bustling production line that made decorations for temples and tombs.

Throughout the city, the archaeologists found tools related to industrial work, including spinning and weaving. They also unearthed metal and glass-making slag, but they haven’t yet found the workshop that made these materials. The archaeologists also found several burials: two unusual burials of a cow or bull, and a remarkable burial of a person whose arms were outstretched to the side and had a rope wrapped around the knees.

The researchers are still analyzing these burials, and hope to determine the circumstances and meaning behind them.

More recently, the team found a vessel holding about 22 pounds (10 kilograms) of dried or boiled meat. This vessel is inscribed with an inscription that reads: Year 37, dressed meat for the third Heb Sed festival from the slaughterhouse of the stockyard of Kha made by the butcher luwy.

“This valuable information not only gives us the names of two people that lived and worked in the city but confirmed that the city was active and the time of King Amenhotep III’s co-regency with his son Akhenaten,” the archaeologists said in the statement.

Moreover, the team found a mud seal that says “gm pa Aton” – a phrase that can be translated into “the domain of the dazzling Aten” – the name of a temple at Karnak built by King Akhenaten.

According to historical documents, one year after this pot was crafted, the capital was moved to Amarna. Akhenaten, who is known for mandating that his people worship just one deity — the sun god Aten – called for this move.

But Egyptologists still wonder why he moved the capital and if the Golden City was truly abandoned at that time. It’s also a mystery whether the city was repopulated when King Tut returned to Thebes and reopened it as a religious center, according to the statement.

Further excavations may reveal the city’s tumultuous history. And there’s still a lot to excavate. “We can reveal that the city extends to the west, all the way to the famous Deir el-Medina” – an ancient worker’s village inhabited by the crafters and artisans who built the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens, Hawass said.

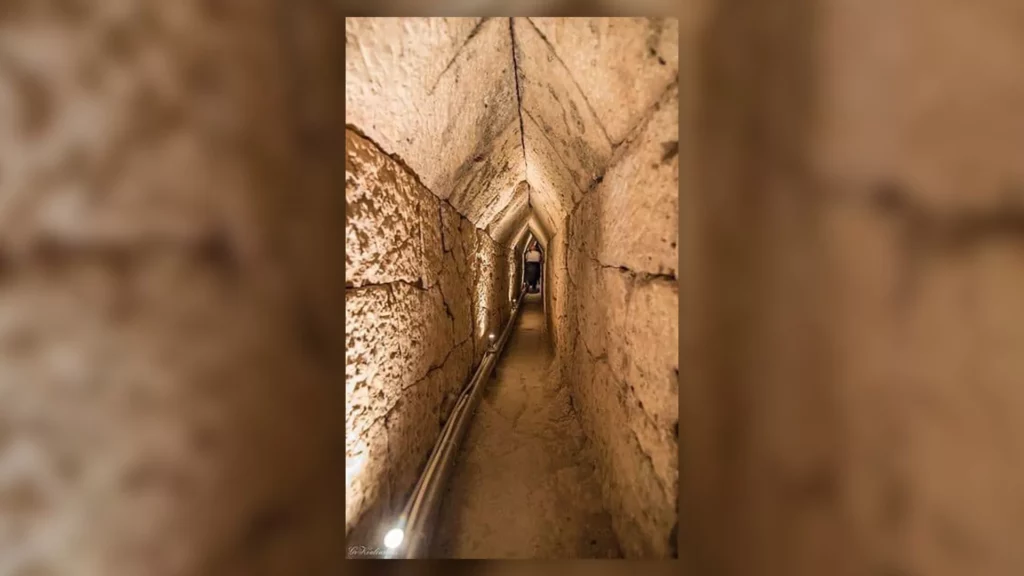

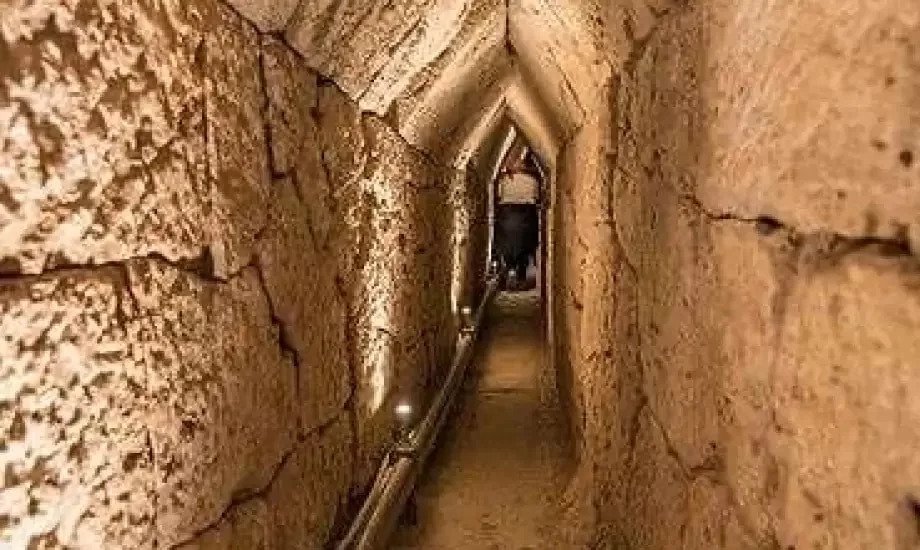

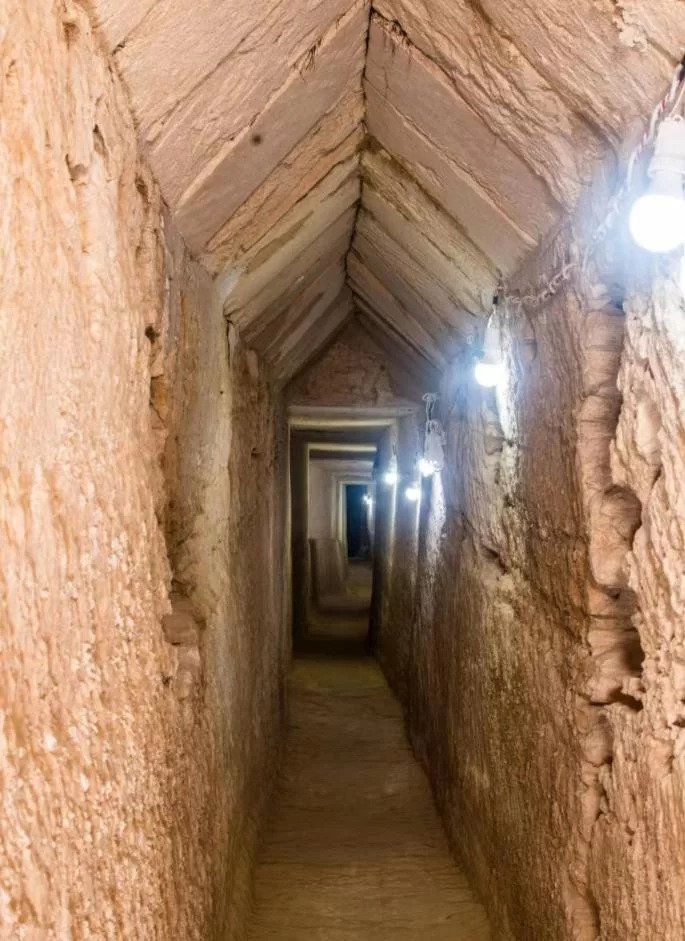

Furthermore, in the north, archaeologists have found a large cemetery that has yet to be fully excavated. So far, the team has found a group of rock-cut tombs that can be reached only through stairs carved into the rock – a feature that is also seen at the Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Nobles.

In the coming months, archaeologists plan to excavate these tombs to learn more about the people and treasures buried there.