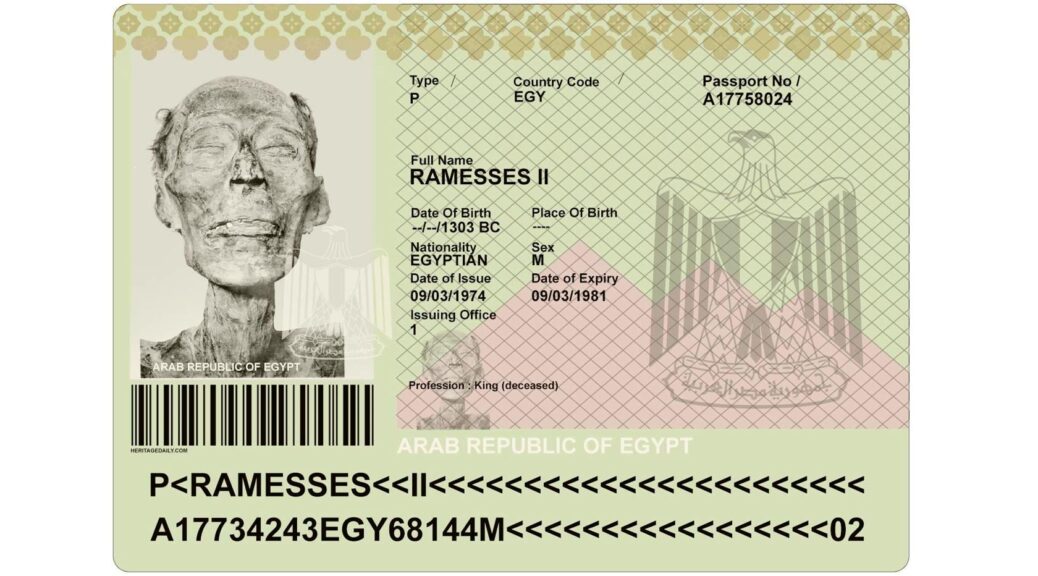

Passport of 3,000-year-old Mummy of Pharaoh Ramesses II Issued for Travelling to France for the necessary repair

Pharoah Ramesses was one of the strongest leaders in ancient Egypt and even when he had died, he was an absolute king. Ramesses, sometimes also known as Ramses, was the greatest and the most famous ruler of the New Kingdom, and ruling the dynasty of Egypt over 66 years.

Born in 1303 BC, Ramesses was named after Ra, the ruler of the sun and ‘Ramesses’ translates to ‘Ra is the one who bore him.’ He fought multiple battles and led several military expeditions. He got hold of the throne when he was only in his teens.

His father, Ramesses I, came from a non-Royal family and was given the crown after the demise of Akhenaten, a pharaoh who tried to convert Egyptians to a newly-introduced monotheistic religion. He made his son a military general when he was merely 10 years old. Egyptians referred to Ramesses II as ‘Ramesses the great.’ He was deeply loved by his masses.

Archaeologists have found numerous Paintings, murals, engravings, and tombs in honor of Ramesses II, praising him. While the exact age is not known, it is believed that Ramesses died when he was about 90 years old.

He had several dental problems and was suffering from arthritis. He outlived many of his wives and even children and took his empire to a new height.

He was buried in the Valley of Kings, originally, but due to the constant threat of being looted, the priests took him out, re-wrapped him, and then placed him in the tomb of queen Ahmose Inhapy only to remove him again and move to Pinedjem’s tomb, a high priest. The linen which covers his body has hieroglyphics depicting the same.

His mummy was first discovered in 1881 and the people who discovered it were shocked to see what they found. Even after hundreds of years, Ramesses’ body was still intact, hair still on his head and his skin was in pristine condition.

The mummy was 5’7 in height, had a strong jaw and an aquiline nose structure. Gaston Maspero, who first unwrapped the mummy, revealed fascinating details about it.

“On the temples, there are a few sparse hairs, but at the poll the hair is quite thick, forming smooth, straight locks about five centimeters in length. White at the time of death, and possibly auburn during life, they have been dyed a light red by the spices (henna) used in embalming… the mustache and beard are thin…

The hairs are white, like those of the head and eyebrows…the skin is of earthy brown, splotched with black… the face of the mummy gives a fair idea of the face of the living king,” he noted.

But, when a group of Egyptologists visited his tomb in 1974, they found that the body of the legendary king was deteriorating rapidly and was in a grave need of repairs.

It was found that bacteria due to humidity had infested the body of the pharaoh, causing it to fall apart. To repair and preserve such an ancient body, experts were needed and at that time, such experts were only found in France.

So, in order to take the mummy to Paris, the authorities issued Ramesses II a valid Egyptian passport, 3,000 years after his death. A picture of his mummy was his passport picture (and you thought you look ugly in your passport id) and his profession was listed as ‘King (Deceased).’

The mummy flew to Paris after formalities and was received with military honors, like a king. After he was repaired, he flew back to Cairo and now resides there in the Egyptian Museum.