New Discovery Reveals Why And When The Sahara Desert Was Green

A pioneering study has shed new light on North African humid periods that have occurred over the past 800,000 years and explains why the Sahara Desert was periodically green.

The research, published in Nature Communications, showed periodic wet phases in the Sahara were driven by changes in Earth’s orbit around the sun and were suppressed during the ice ages.

For the first time, climate scientists simulated the historic intervals of ‘greening’ of the Sahara, offering evidence for how the timing and intensity of these humid events were also influenced remotely by the effects of large, distant, high-latitude ice sheets in the Northern Hemisphere.

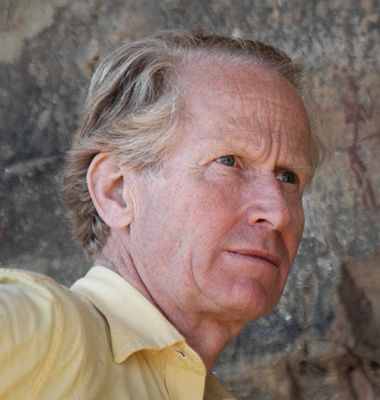

Lead author Dr. Edward Armstrong, a climate scientist at the University of Helsinki and University of Bristol, said, “The cyclic transformation of the Sahara Desert into savannah and woodland ecosystems is one of the most remarkable environmental changes on the planet.”

“Our study is one of the first climate modeling studies to simulate the African Humid Periods with comparable magnitude to what the paleoclimate observations indicate, revealing why and when these events occurred.”

There is widespread evidence that the Sahara was periodically vegetated in the past, with the proliferation of rivers, lakes and water-dependent animals such as hippos, before it became what is now desert.

These North African Humid Periods may have been crucial in providing vegetated corridors out of Africa, allowing the dispersal of various species, including early humans, around the world.

The so-called “greenings” are thought to have been driven by changes in Earth’s orbital conditions, specifically Earth’s orbital precession. Precession refers to how Earth wobbles on its axis, which influences seasonality (i.e., the seasonal contrast) over an approximate 21,000-year cycle. These changes in precession determine the amount of energy received by the Earth in different seasons, which in turn controls the strength of the African Monsoon and the spread of vegetation across this vast region.

A major barrier to understanding these events is that the majority of climate models have been unable to simulate the amplitude of these humid periods, so the specific mechanisms driving them have remained uncertain.

This study deployed a recently-developed climate model to simulate the North African Humid periods to greatly advance understanding of their driving mechanisms.

The results confirm the North African Humid Periods occurred every 21,000 years and were determined by changes in Earth’s orbital precession. This caused warmer summers in the Northern Hemisphere, which intensified the strength of the West African Monsoon system and increased Saharan precipitation, resulting in the spread of savannah-type vegetation across the desert.

The findings also show the humid periods did not occur during the ice ages, when there were large glacial ice sheets covering much of the high latitudes. This is because these vast ice sheets cooled the atmosphere and suppressed the tendency for the African monsoon system to expand.

This highlights a major teleconnection between these distant regions, which may have restricted the dispersal of species, including humans, out of Africa during the glacial periods of the last 800,000 years.

Co-author Paul Valdes, Professor of Physical Geography at the University of Bristol, said, “We are really excited about the results. Traditionally, climate models have struggled to represent the extent of the ‘greening’ of the Sahara. Our revised model successfully represents past changes and also gives us confidence in their ability to understand future change.”

The research, including climate scientists from the University of Birmingham, is part of a project at the University of Helsinki, which studies the impacts of climate on past human distributions and evolution of their ecological niche.

Co-author Miikka Tallavaara, Assistant Professor of Hominin Environments at the University of Helsinki, said, “The Sahara region is kind of a gate controlling the dispersal of species between both North and Sub-Saharan Africa, and in and out of the continent.”

“The gate was open when Sahara was green and closed when deserts prevailed. This alternation of humid and arid phases had major consequences for the dispersal and evolution of species in Africa.

Our ability to model North African Humid periods is a major achievement and means we are now also better able to model human distributions and understand the evolution of our genus in Africa.”