The Hanging Pillar of Lepakshi Temple that Challenges Gravity

Gravity, the powerful force that rules our world, seems rigid and invincible. Still, tucked away in southern India is a beautiful architectural marvel known as the “Hanging Pillar,” which is said to challenge this very force. Yes! You read that right.

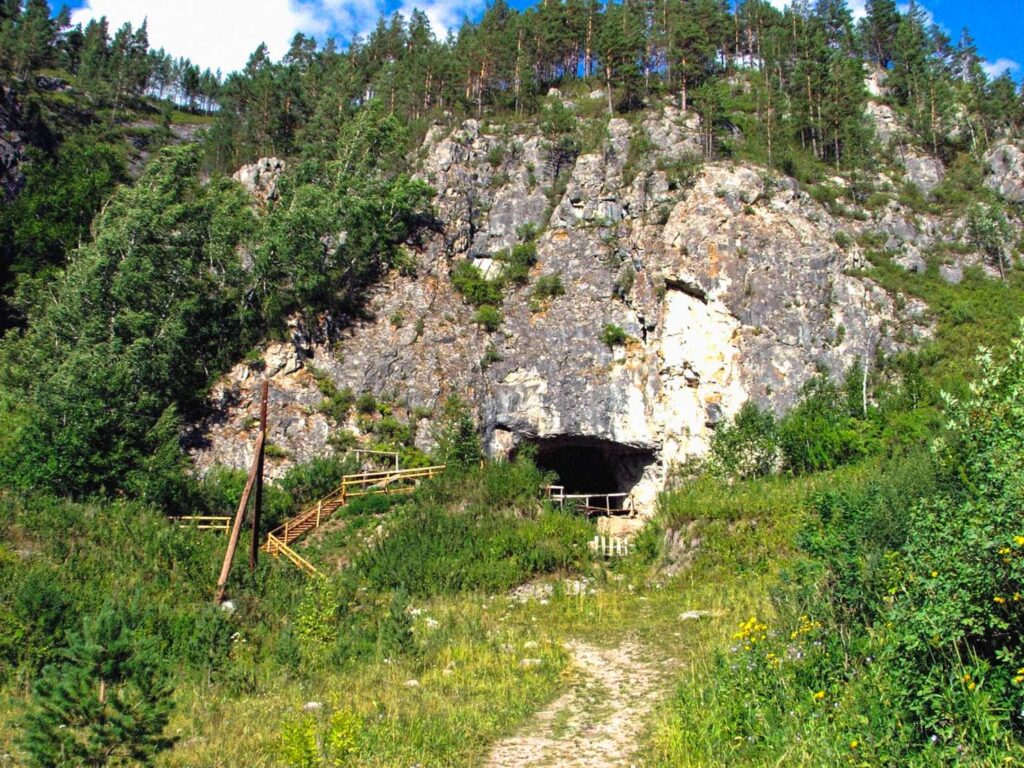

It dates back to the 16th century. This remarkable monument is located within the Veerabhadra Temple in Lepakshi and is dedicated to Lord Shiva’s furious manifestation, Veerabhadra.

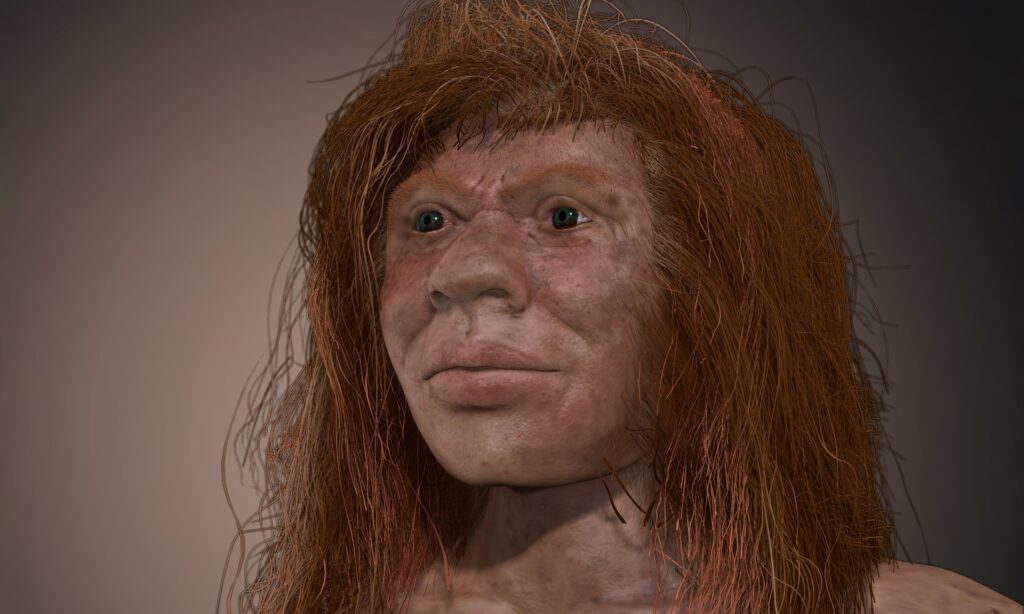

The temple is adorned with beautiful sculptures and paintings that grace almost every visible surface. It displays the distinguishing Vijayanagara-style architecture. The magnificence and historical importance of Lepakshi Temple makes it one of the most notable Vijayanagara temples, revered as a nationally conserved monument.

The temple is divided into three sections: the Garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum), the Arda Mantapa (antechamber), and the Mukha Mantapa/Natya Mantapa/Ranga Mantapa (assembly hall). Nonetheless, the Hanging Pillar, indeed, is a testament to architectural ingenuity.

Location and Historical Significance

The Lepakshi Temple, also known as the “Veerbhadra Temple,” is located in the Lepakshi village of Anantapur District in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. It is an outstanding example of both engineering innovation and artistic skill. It has many components that add to its archaeological and aesthetic splendor, such as exquisitely carved statues of musicians and saints and those showing a sacred couple of deities – Lord Shiva and Goddess Parvati. In addition to its architectural significance, the temple is highly revered since the Skanda Purana refers to it as a “divyakshetra,” a place of worship of Lord Shiva.

The Lepakshi Temple was built in the 1530s CE by two brothers named Virupanna Nayaka and Viranna. During King Achutaraya’s reign, both served as governors for the Vijayanagar Empire. You can find many Kannada language (predominantly spoken in southwestern India) inscriptions here.

The origins of Lepakshi are shrouded in mythology and narratives. According to one legend, Jatayu, a vulture deity depicted in the epic Ramayana, fought Ravana fiercely to save Sita, Lord Rama’s wife. Jatayu bravely fought after being hurt before collapsing to the ground. While Lord Rama and his brother Lakshmana were searching for Sita, they found Jatayu battling for his life, holding his last breath. When he found Jatayu in such a helpless state, overcome with grief, Lord Rama said the words “Le Pakshi,” which means “rise, bird” in Telugu.

The complex contains several other temples besides the Veerabhadra Temple, which is under consideration for UNESCO’s world heritage list (tentative list.) These include the shrines of Hanumalinga, Raghunatha, Parvati, Ramalinga, and Papanasesvara. There are many other attractions in this area, in addition to the well-known Hanging Pillar.

The Monolithic Bull, called the Nandi, is another noteworthy feature of Lepakshi. This enormous bull (approximately 20-foot high and 30-foot long) sculpture was cut from a single granite rock.

The Naga Shiva Linga is another impressive piece of architecture. The structure’s seven-headed hooded serpent and lingam (a representation of Lord Shiva) together make for a stunning sight. Lepakshi provides a fascinating cultural and historical experience for sure.

Is the Hanging Pillar Actually a Miracle?

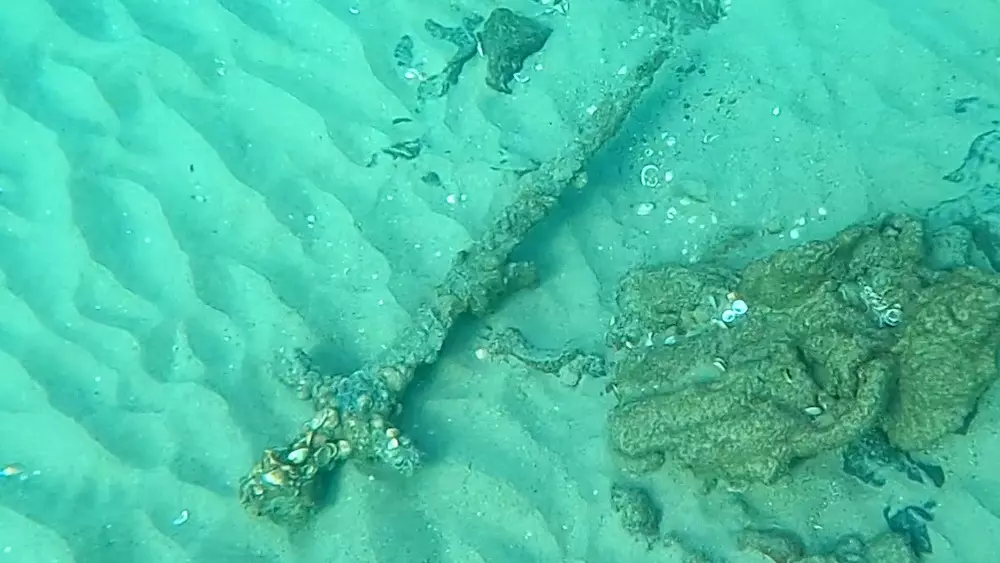

The Hanging Pillar in Lepakshi, which is made of granite, is a spectacular phenomenon that draws a lot of attention. Among the temple’s 70 pillars, this one stands out because it is hanging without touching the ground. Owing to this, many visitors to the temple cannot resist passing a piece of cloth or paper beneath the bottom of the pillar to confirm its authenticity.

The puzzle of how this pillar manages to remain hung without any support is still unexplained and remains a mystery. It adds an aura of intrigue and surprise to the temple, supported by around 70 pillars. The pillar is also engraved with beautiful carvings.

As per the local folklore, in India’s pre-independence era, a curious British engineer once tried to move the hanging pillar to figure out the source of its support. Realizing the importance of each pillar in safeguarding the balance of the whole structure, he wisely stopped, saving the structure from collapsing. Despite a slight displacement, the pillar stood still. This led to the displacement of the hanging pillar.

Another folktale talks of British engineers who wanted to make renovations and chose to remove the pillar. It was so perfectly fixed that they couldn’t move it. But they didn’t give up. Therefore, they could only move it slightly, and they realized it wouldn’t be possible to take it out completely, resulting in the pillar being slightly displaced from its original position. Considering these are folklore, the mystery still prevails around the hanging pillar.