Cache of Medieval Jewelry Unearthed in Russia

Archaeologists in southwest Russia have unearthed a trove of medieval silver at a site where the treasure was often hidden from an invading Mongol army in the 13th century — but oddly it seems to have been buried there at least 100 years before the Mongols swept through.

The trove of silver pendants, bracelets, rings, and ingots was found during excavations earlier this year near the site of Old Ryazan, the fortified capital of a Rus principate that was besieged and sacked by Mongols in 1237.

The Mongol attack was particularly bloodthirsty; historical accounts report that the invaders left no one alive in Old Ryazan and archaeologists have discovered nearly 100 severed heads and several mass graves there from the time.

The hidden treasure was found in the forested bank of a ravine several hundred yards away from two small medieval settlements that had existed there; archaeologists also found remains of a cylindrical container probably made from birch bark that had once held the trove, according to a translated statement from the Russian Academy of Sciences.

The treasure includes 14 ornate bracelets, seven rings and eight “neck hryvnias” — a type of pendant worn around the neck that gave its name to the modern Ukrainian currency — and weighs 4.6 pounds (2.1 kilograms).

The jewelry is finely made, and archaeologists think its mixed composition shows it was a trove of accumulated wealth rather than a set of jewellery for a particular costume.

Golden Horde

Ryazan was one of several medieval principalities of the Rus people in the 11th century. It was centered on the city now known as Old Ryazan — about 30 miles (50 km) southeast of the modern city of Ryazan and about 140 miles (225 km) southeast of Moscow — and grew powerful enough to occasionally go to war with its neighbours.

But Ryazan was east of the other Rus principalities, and so it was the first to fall to an invading Mongol army from the far east, led by a grandson of Genghis Khan called Batu Khan.

The Mongols first defeated the Ryazan army in battle and then besieged the capital city, using catapults to destroy its fortifications.

The inhabitants of the city repelled the besiegers for almost a week — but in the end, the Mongols plundered the city, killed its prince, his family, and its inhabitants, and burned all that remained to the ground. A Rus chronicler noted “there was none left to groan and cry.”

Batu Khan’s armies went on to conquer and subjugate other Rus principalities until the Mongol leader’s death in 1255; his successors ruled much of southern and central Russia as the Golden Horde — from the Turkic phrase “Altan Orda,” which means “golden headquarters,” possibly from the golden colour of Batu Khan’s tent.

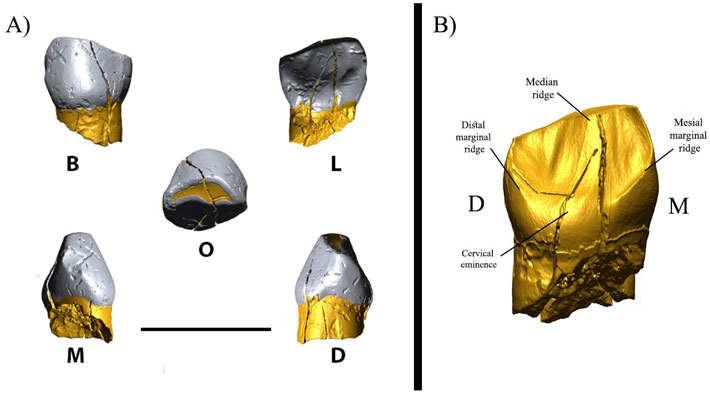

The hidden hoard of medieval silver, including several finely-made bracelets, was found at the site of Old Ryazan which was destroyed by an invading Mongol army in the 13th century. Archaeologists say the silver bracelets and other items of jewellery in the medieval hoard are especially well-made.

Among the treasure are several “seven ray rings” that are thought to represent the rays of the sun. Seven-ray rings became a distinctive feature of early medieval Russian jewellery; it’s thought their design was introduced from the far east.

Some of the bracelets, including this one of braided silver wire, are thought by their style to date from the 10th and 11th centuries. The ends of some of the bracelets are hollow and delicately embossed with intricate ornamental designs, including stylized palm trees that suggest an eastern and southern influence. Some of the bracelets are embossed at the ends with crosses that presumably portray Christian crucifixes.

Several buried treasures found at Old Ryazan date from the siege of the city in 1237, but archaeologists think this hoard of silver was buried about 100 years before that.

Hidden treasure

The practice of hiding treasure to prevent the invading Mongols from finding it seems to have been relatively common during the siege — more than a dozen hidden troves have now been found nearby, including the famous Old Ryazan Treasure, a collection of bejewelled royal regalia which was discovered by chance in the 19th century and is now on display in a nearby cathedral.

Somewhat surprisingly, however, the newly-discovered trove seems to have been hidden away between the end of the 11 century and the beginning of the 12th century — a century before the Mongol invasion, based on analysis of the style of the jewelry and ceramics found nearby, the RAS archaeologists said.

“The… treasure is clearly older than the Old Ryazan Treasure and includes jewellery made with simpler techniques and a more archaic manner,” the statement read.

The trove includes several six-sided “grivna,” a relatively small type of standardized silver ingot that could be used as jewellery, a measure of weight, or currency during the medieval Rus period. The bracelets are especially well made. The most complex has three silver braids and are ornamented at the ends with embossed crosses and palm leaves, the archaeologists said.

“Further studies of the treasure items, the technique of their manufacture, the composition of the metal will complement our knowledge of the early history of Old Ryazan,” they wrote; “possibly it will reveal the historical context of the concealment of the treasure.”