Oldest evidence of life on land found in 3.48 billion-year-old Australian rocks

Whether you are looking at an actual fossil or crinkles in the rock itself can be hard to tell in the search for the earliest life on earth. The discovery of 3.5 billion – year – old fossils in the Australian desert in the 1980s has long shadowed these doubts Now, scientists think they ended up putting the matter to bed

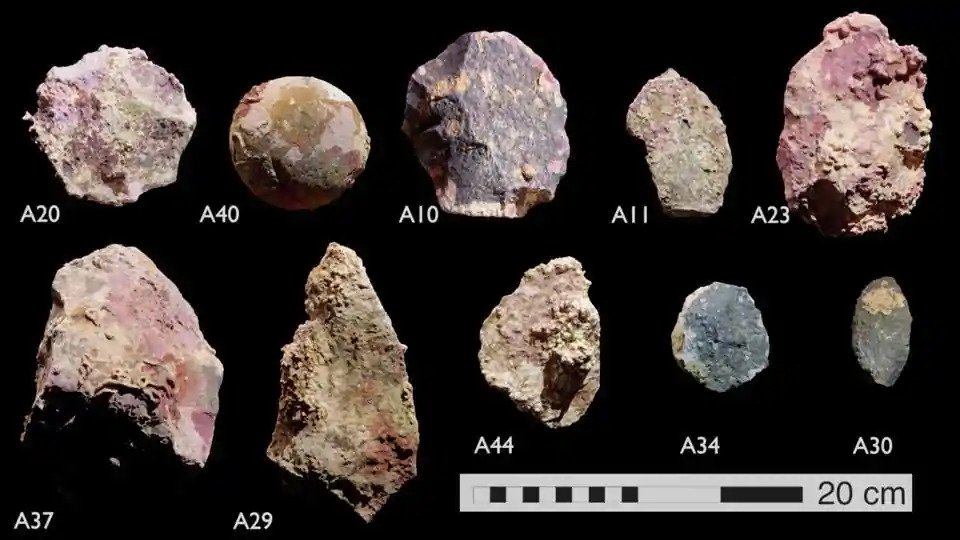

In ancient fossilized microbe formations called stromatolites, found in the Dresser Formation fossil site of the Pilbara region, researchers have finally detected traces of organic matter.

“This is an exciting discovery – for the first time, we’re able to show the world that these stromatolites are definitive evidence for the earliest life on Earth,” said geologist Raphael Baumgartner of the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Australia.

You may remember the time scientists claimed to have found 3.7 billion-year-old fossils in Greenland. Later research determined that these fossils were just plain old rocks, and the crown was returned to the Pilbara fossils.

But, although everyone was pretty sure the Pilbara fossils were the real deal, it hadn’t actually been conclusively proven. They had the shape and structure of microbial stromatolites, but no evidence of organic matter to back it up.

There’s more riding on this than a tiara and a sash reading “Oldest fossils.” It’s deeply relevant to one of the fundamental questions about our very existence: When and how did life develop on this sloshy blue marble?

So, Baumgartner and his team went digging. Not literally, though; they analyzed previously drilled core samples from deep underground, below where the rocks could have been affected by the weather. This means these samples were much better preserved than those from the surface; in their paper, the team said the preservation was “exceptional”.

The researchers analyzed the samples in thin slices using multiple techniques, including scanning electron microscopy and scanning transmission electron microscopy; energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, and Raman spectroscopy; nano-scale secondary ion mass spectrometry; and stable carbon isotope analysis.

If that seems like overkill, well, it’s not really. If one of those lines of inquiry showed a positive result and the rest didn’t, it would mean much shakier ground for drawing a conclusion. But things looked good across the board.

The team’s analyses revealed that the stromatolites are predominantly made up of a mineral called pyrite, riddled with nanoscopic pores. And in the pyrite are inclusions of nitrogen-bearing organic material, as well as strands and filaments of organic matter that closely resemble the remnants of biofilms formed by microbe colonies.

“The organic matter that we found preserved within pyrite of the stromatolites is exciting – we’re looking at exceptionally preserved coherent filaments and strands that are typically remains of microbial biofilms,” Baumgartner said.

“I was pretty surprised – we never expected to find this level of evidence before I started this project.”

Previously, a different team of UNSW researchers found evidence of 3.48 billion-year-old microbes in hot spring deposits in the Pilbara.

Because those deposits are about the same age as the crust of Mars, it’s thought that they could tell us how to find potential fossils on Mars – especially since there’s evidence the Red Planet once had hot springs too.

Indeed, NASA has been investigating the Pilbara to try to learn the possible geological signatures that could indicate the presence of stromatolites.

“Understanding where life could have emerged is really important in order to understand our ancestry,” Baumgartner said. “And from there, it could help us understand where else life could have occurred – for example, where it was kick-started on other planets.”