Bulgarian Gangsters Busted for Looting 4,600 Ancient Artifacts from Historical sites

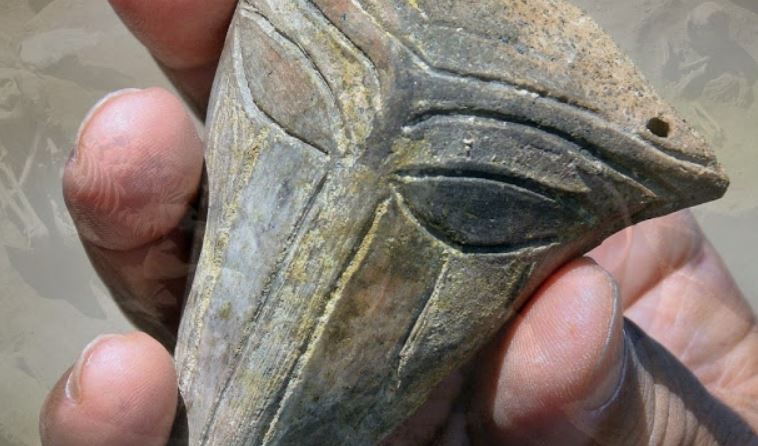

After two years of investigation by Bulgarian, British, and German authorities, an international crime ring planning to smuggle thousands of ancient artifacts into England has been caught. According to The Times, the 4,600 items ranged from spears and coins to funeral urns, ceramics, and arrowheads.

The artifacts span from the Bronze and Iron Age to the Middle Ages. Some of the relics were illegally excavated from Roman-era military camps in Bulgaria. They were then smuggled into Germany, with the ultimate goal being legitimate sales in the London art market.

According to Heritage Daily, the gang chose Germany as its transit country and hired private U.K. transportation companies to bring the goods into England. Little did they know that Bulgarian police received a tip-off in March 2018 — after which surveillance on the group began in earnest.

Were it not for the successful sting operation on behalf of authorities from three different countries, the eight individuals now under arrest would’ve made several millions of euros. The remarkable goods, meanwhile, would have been likely been dispersed across private homes around the world.

A task force came together to stop the smugglers, coordinated by Europol and conducted by the General Directorate for the Fight against Organized Crime of the Bulgarian Ministry of Internal Affairs.

They worked for hand in hand with the British Metropolitan Police, as well as the German State Criminal Police of Bavaria, under an umbrella operation called MEDICUS.

As the existence of the looted goods wasn’t officially known, proving their illicit origin is difficult to do. With forged provenance and documentation on top, the legal ownership of these artifacts would appear entirely legitimate to auction houses or interested parties.

Only diligent surveillance and monitoring of the group allowed authorities to confirm their suspicions. Five of the eight gang members were arrested before leaving Bulgaria. Three of them were permitted to enter the U.K., thus committing the crime of smuggling goods across, before being arrested.

The group of three was detained after entering the U.K. in Dover. Two men aged 19 and 55 and one 67-year-old women were arrested. According to The Southend Standard, the charge was suspicion of handling stolen goods, and the artifacts concealed in the suspects’ vehicle quickly confirmed as much.

“The arrests were made as part of an ongoing investigation into the theft of cultural artifacts in Europe which is being led by detectives from the Met’s art and the antique unit,” the Metropolitan Police said.

This sting operation dates to October 2019, but Europol has only now felt assured enough that publishing any details won’t jeopardize other operations nor the trials of these eight individuals. Europol explained in a statement that auction houses are commonly part of such illegal sales.

“This case confirms that the most common way to dispose of archaeological goods illegally excavated is by entering the legitimate art market,” the agency said.

Last month, the arts and crafts chain Hobby Lobby was caught having illegally purchased an ancient tablet inscribed with part of the Epic of Gilgamesh.

On top of that, the $1.6 million artifacts were only one of the thousands of relics looted and smuggled from Iraq that the company had illegally bought.

Hopefully, more time and effort is spent on preventing this seemingly ubiquitous practice. Cultural artifacts belong to the people of their countries — and should be displayed for them to cherish and learn from. At least in this latest case, it appears that this kind of justice is being fought for.