460-Year-Old Hunting Bow Discovered Underwater in Alaska’s Lake Clark National Park

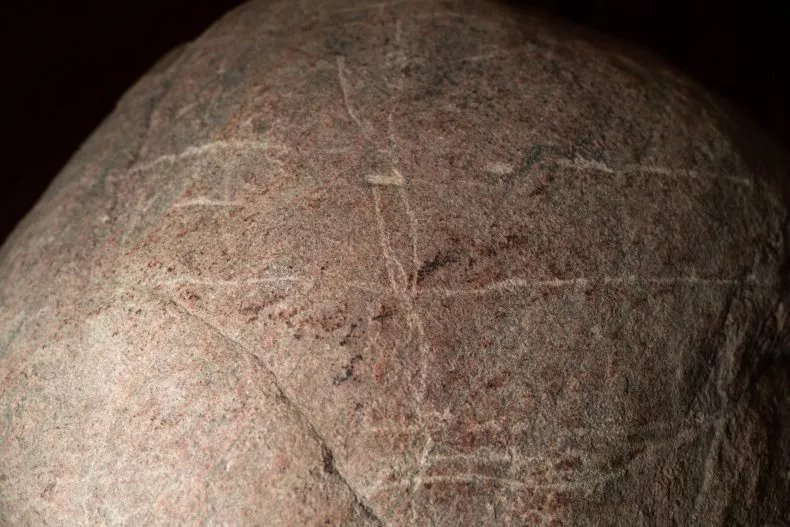

National Park Service employees made an unlikely discovery in the backcountry of Lake Clark National Park and Preserve in Alaska this past September: a 54-inch wooden hunting bow that was found under 2 feet of water, but still intact.

Scientists and archaeologists are analyzing the hunting bow in an attempt to learn more about its origin and history. According to radiocarbon dating conducted by the NPS, the bow is estimated to be 460 years old, ranging in origin between 1506 and 1660. The real mystery lies not in how old the bow is, but where it came from.

Park officials found the antique weapon on Dena’ina lands, an Athabascan indigenous people whose ancestral lands cover much of South-Central Alaska, including a large portion of Lake Clark National Park and Preserve.

However, preliminary research suggests that the handcrafted bow might not be of Dena’ina origin. After consulting with Elders and comparing the bow with similar artefacts from that time period, experts believe the artefact has more in common with a Yup’ik or Alutiq style bow.

The homeland of the Dena’ina, which comprises roughly 41,000 square miles along the coast of the Cook Inlet, is called the Denaʼina Ełnena, and it includes lands where present-day Anchorage is located. Dena’ina lands also cover much of Lake Clark National Park and Preserve, including the lake itself, which is traditionally known as “Qizhjeh Vena”.

The Dena’ina culture, which prioritizes a connection to nature and respect for the wilderness, has a rich history in the Athabascan region.

“We call this ‘K’etniyi’ meaning ‘it’s saying something,” writes Karen Evanhoff, a cultural anthropologist for Lake Clark National Park and Preserve.

Anthropologists have also learned that the Dena’ina regularly interacted with indigenous peoples from neighbouring regions, including the Yup’ik who live in the coastal region of southwestern Alaska, from Bristol Bay along the Bering coast and up to Norton Sound.

This intercultural history would help explain how a Yup’ik bow might end up on Dena’ina homelands in the first place.

“For the Dena’ina people, trading and sharing knowledge with their Yup’ik neighbours as well as other groups such as the Tanana, Tlingit, Ahtna, Deg Hit’an and coastal residents of Prince William Sound and Kodiak was common,” the NPS explains.

Experts are still working to piece together the clues, however, and the cultural history of the bow is just one part of the puzzle.

Soon after it was discovered, the bow was transported to the Park Service’s Regional Curatorial Center in Anchorage, where experts have inspected the artefact and analyzed its natural origins. As part of this analysis, the NPS brought in Dr. Priscilla Morris, a wood identification consultant with the U.S. Forest Service.

“After inspecting the artefact, I am leaning towards spruce,” Morris told the NPS after taking a closer look at the bow. “Birch is also a suspected species, but I did not see any anatomical characteristics that lead me to believe birch over spruce.”

Morris explained that her hypothesis was based solely on what she could see underneath a hand lens and that a concrete identification would require looking at a cut-up sample underneath a microscope.

This is unlikely to happen anytime soon, however, as the NPS wants to preserve the bow and keep it intact for the time being. As NPS archaeologist Jason Rogers explained, these discoveries are rare in Alaska, especially when compared to Europe and other more developed parts of the world.

“In Alaska, we just don’t have that kind of development so it’s very rare,” Rogers told the local news earlier this week. “It’s very rare for us to come across material like this.”