Cannabis originated in China, genetic analysis reveals

People feeling the effects of marijuana are prone to what scientists call “divergent thinking,” the process of searching for solutions to a loosely defined question. Here is one to ponder: Where did the weed come from? No, not where it was bought, but where and when was the plant first domesticated.

Many botanists believe that the Cannabis sativa plant was first domesticated in Central Asia. But a study published Friday in the journal Science Advances suggests that East Asia is the more likely source and that all existing strains of the plant come from an “ancestral gene pool” represented by wild and cultivated varieties growing in China today.

The study’s authors found that the plant was a “primarily multipurpose crop” grown about 12,000 years ago during the early Neolithic period, probably for fibre and medicinal uses.

Farmers began breeding the plant specifically for its mind-altering properties about 4,000 years ago, as cannabis began to spread into Europe and the Middle East, the authors of the study said.

Michael Purugganan, a professor of biology at New York University who read the study, said the usual assumption about early humans was that they domesticated plants for food.

“That seems to be the most pressing problem for humans then: How to get food,” said Purugganan, who was not involved in the research. “The suggestion that even early on they were also very concerned with fibre and even intoxicants is interesting. It would bring to question what were the priorities of these Neolithic societies.

A 2016 study by other scientists said that the earliest records for cannabis were mostly from China and Japan, but most botanists believe that it was probably first domesticated in the eastern part of Central Asia, where wild varieties of the plant are widespread.

Gene study

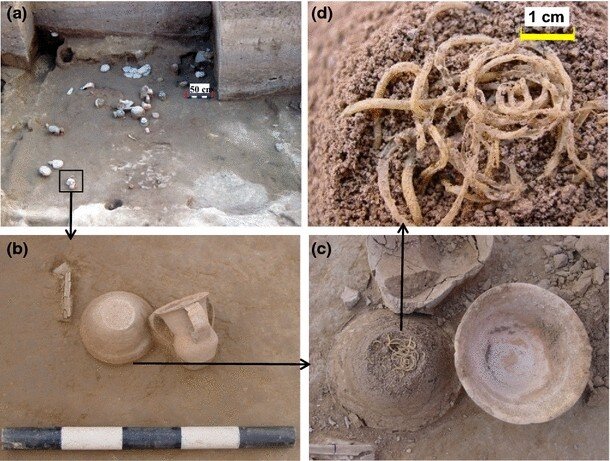

Genetic sequencing for the latest study suggests that the species has a “single domestication origin” in East Asia, the researchers wrote. By sequencing genetic samples of the plant, they found that the species had most likely been domesticated by the early Neolithic period. They said their conclusion was supported by pottery and other archaeological evidence from the same period that was discovered in present-day China, Japan and Taiwan.

But Purugganan said he was sceptical about conclusions that the plant was developed for drug or fibre use 12,000 years ago since archaeological evidence show the consistent use or presence of cannabis for those purposes began about 7,500 years ago. “I would like to see a much larger study with a larger sampling,” he said.

Luca Fumagalli, an author of the study and a biologist in Switzerland who specialises in conservation genetics, said the theory of a Central Asian origin was largely based on observational data of wild samples in that region. “It’s easy to find feral samples, but these are not wild types,” Fumagalli said. “These are plants that escaped captivity and readapted to the wild environment. “By the way, that’s the reason you call it to weed, because it grows anywhere,” he added.

The study was led by Ren Guangpeng, a botanist at Lanzhou University in the western Chinese province of Gansu. Ren said in an interview that the original site of cannabis domestication was most likely northwestern China and that the finding could help with current efforts in the country to breed new types of hemp.

To conduct the study, Ren and his colleagues collected 82 samples, either seeds or leaves, from around the world. The samples included strains that had been selected for fibre production and others from Europe and North America that were bred to produce high amounts of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the plant’s most mood-altering compound.

Fumagalli and his colleagues then extracted genomic DNA from the samples and sequenced them in a lab in Switzerland. They also downloaded and reanalyzed sequencing data from 28 other samples. The results showed that the wild varieties they analyzed were in fact “historical escapes from domesticated forms,” and that existing strains in China — cultivated and wild — were their closest descendants of the ancestral gene pool.

“Although additional sampling of feral plants in these key geographical areas is still needed, our results, which are based on very broad sampling already, would suggest that pure wild progenitors of C. Sativa have gone extinct,” they wrote As hemp’s function as a global source for textiles, food and oilseed dried up in the 20th century, the use of cannabis as a recreational drug increased, the new study noted. But there are still “large gaps” in knowledge about its domestication history, it said, in large part because the plant is illegal in many countries.

It can also be hard to understand precisely how plant species are domesticated in the first place, said Catherine Rushworth, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Minnesota who studies plant evolution.

Although scientists can make some basic predictions about how a given plant species will diverge in nature, she added, such predictions “go out the window” when a natural selection process is driven by humans. “So, for example, we might think that species would diverge when they’re adapting to different habitats, or to different pollinators,” she said. “But people are often the pollinators and people have created those habitats.