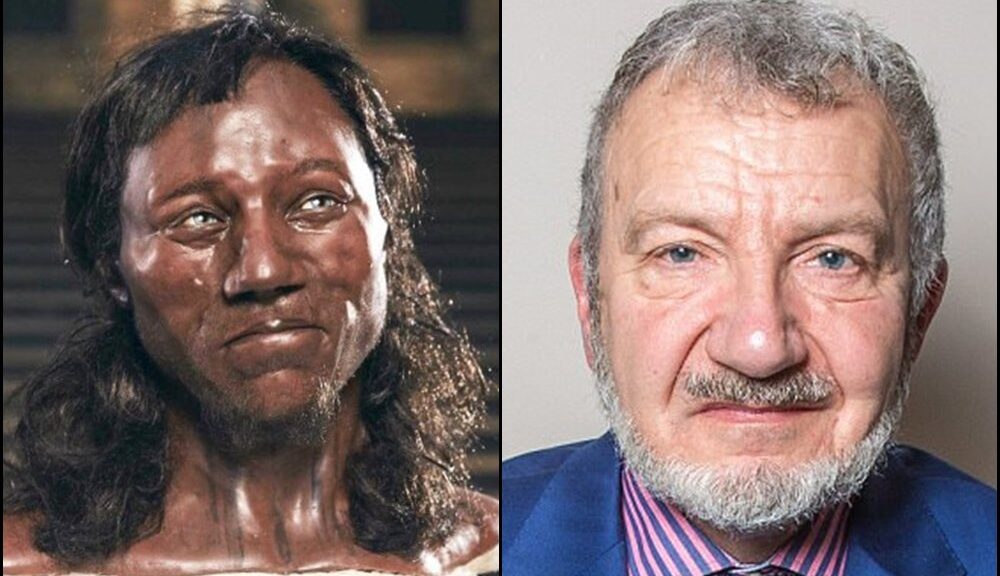

An English Teacher of History and a 9000-year-old cheddar man have the same DNA

Separated by 10,000 years but linked by DNA! A 9,000 year old skeleton’s DNA was tested and it was concluded that a living relative was teaching history about a half mile away, tracing back nearly 300 generations!

Four years before, when Adrian Targett, a retired history teacher from Somerset, walked into his local news-agent’s, he was startled to see a familiar face staring up at him. That face, appearing on the front page of several newspapers, belonged to a distant relative of his — around 10,000 years distant, actually — known as Cheddar Man.

Ancient DNA from Cheddar Man, a Mesolithic skeleton discovered in 1903 at Gough’s Cave in Cheddar Gorge, Somerset, has helped Museum scientists paint a portrait of one of the oldest modern humans in Britain.

This discovery is consistent with a number of other Mesolithic human remains discovered throughout Europe. Cheddar Man is the oldest complete skeleton to be discovered in the UK and has long been hailed as the first modern Briton who lived around 7,150 BC. His remains are kept by London’s Natural History Museum, in the Human Evolution gallery.

The Cheddar Man earned his name, not because of his fondness for cheese, which likely wasn’t cultivated until around 3,000 years later, but because he was found in Cheddar Gorge in Somerset, England (which is, incidentally, where cheddar cheese originates).

Some 25 years ago, in an amazing piece of DNA detective work, using genetic material taken from the cavity of one of Cheddar Man’s molar teeth, scientists were able to identify Mr Targett, 62, as a direct descendant.

Analysis of his nuclear DNA indicates that he was a typical member of the Western European hunter-gatherer population at the time, with lactose intolerance, probably with light-coloured eyes (most likely green but possibly blue or hazel), dark brown or black hair, and dark/dark-to-black skin, although an intermediate skin colour cannot be ruled out.

There are a handful of genetic variants linked to reduced pigmentation, including some that are very widespread in European populations today. However, Cheddar Man had “ancestral” versions of all these genes, strongly suggesting he would have had a “dark to black” skin tone.

Now Cheddar Man is back in the headlines because a new study of his DNA, using cutting edge technology, has enabled researchers to create a forensic reconstruction of his facial features, skin and eye colouring, and hair texture. And the biggest surprise is the finding that this ancient Brit had ‘dark to black skin — and bright blue eyes. (A previous reconstruction, before detailed genetic sequencing tests were available, assumed a white face, brown eyes and a ‘cartoon’ caveman appearance.)

No one had thought to tell Mr Targett any of this or invite him to the unveiling of the new reconstruction of his ancestor at the Natural History Museum on Monday.

‘I do feel a bit more multicultural now,’ he laughs. ‘And I can definitely see that there is a family resemblance. That nose is similar to mine. And we have both got those blue eyes.’

The initial scientific analysis in 1997, carried out for a TV series on archaeological findings in Somerset, revealed Mr Targett’s family line had persisted in the Cheddar Gorge area for around nine millennia, their genes being passed from mother to daughter through what is known as mitochondrial DNA which is inherited from the egg.

To put it simply, Adrian Targett and Cheddar Man have a common maternal ancestor.

It is only Cheddar Man’s skin colouring that marks the difference across this vast space of time. It was previously assumed that human skin tones lightened some 40,000 years ago as populations migrated north out of the harsh African sunlight where darker skin had a protective function.

At less sunny latitudes, lighter skin would have conferred an evolutionary advantage because it absorbs more sunlight which is required to produce vitamin D, a nutrient vital for preventing disabling illnesses such as bone disease rickets. Later, when farming crops began to replace hunter-gatherer lifestyles and communities ate less meat, offal and oily fish — a dietary source of vitamin D — paler skins would have conferred an even greater advantage and accelerated the spread of relevant genes.

However, Cheddar Man’s complexion chimes with more recent research suggesting genes linked to lighter skin only began to spread about 8,500 years ago, according to population geneticists at Harvard University.

They report that over a period of 3,000 years, dark-skinned hunter-gatherers such as Mr Targett’s ancestors interbred with early farmers who migrated from the Middle East and who carried two genes for light skin (known as SLC24A5 and SLC45A2).

It is no surprise Cheddar Gorge remains Britain’s prime site for Palaeolithic human remains. Cheddar Man was buried alone in a chamber near a cave mouth. But it’s not just Adrian Targett who has links with him. Indeed for many modern Britons, Cheddar Man’s true face offers a uniquely close DNA encounter with their past. Modern Britons draw about 10 per cent of their genetic ancestry from the West European hunter-gatherer population from which Cheddar Man sprang.