A Massive Roman Villa Has Been Found In Oxfordshire, England

In Oxfordshire, the second largest Roman villa ever found in England, the remains of a huge Roman villa dating back to 99 AD have been discovered.

As part of a four-month excavation project, archeologists excavated the remains of the historic building, which is believed to be larger than the Taj Mahal mausoleum.

The foundation measures 278 feet by 278 feet. The findings so far include coins and boar tusks alongside a sarcophagus that contains the skeletal remains of an unnamed woman.

“Amateur detectorist and historian Keith Westcott discovered the ancient remains beneath a crop in a field near Broughton Castle near Banbury,” according to HiTech.

Westcott, 55, decided to investigate the site after hearing that a local farmer, John Taylor, had plowed his tractor into a large stone in 1963. Taylor said he saw a hole had been made in the stone and when he reached inside, he pulled out a human bone.

This was the woman’s body — experts believe she died in the 3rd century. The land previously belonged to Lord and Lady Saye and Sele, the parents of Martin Fiennes, who now owns the land.

The Daily Mail reports that Martin Fiennes “works as a principal at Oxford Sciences Innovation and is the second cousin of British explorer Ranulph Fiennes and third cousin of actors Ralph and Joseph Fiennes.”

According to the Daily Mail, Westcott had a “eureka moment” when he found “a 1,800 year-old tile from a hypocaust system, which was an early form of central heating used in high-status Roman buildings.”

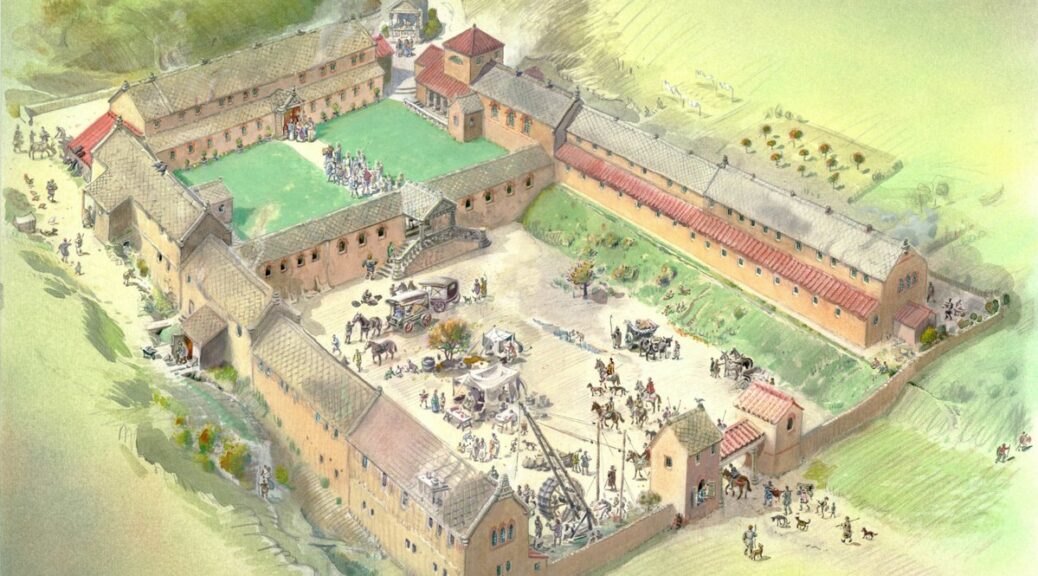

Using X-ray techniques such as magnetometry, the walls, room outlines, ditches, and other infrastructures were revealed. The villa’s accommodation would have included a bath-house with a domed roof, mosaics, a grand dining room, and kitchens.

The largest Roman villa previously found in England is the Fishbourne Palace in West Sussex, which dates back to 75 AD.

The palace at Fishbourne was one of the most noteworthy structures in Roman Britain. Only discovered in the 1960s, the site has been extensively excavated, revealing that it was originally a military site. Lying close to the sea, Fishbourne was ideal as a depot to support Roman campaigns in the area.

Built on four sides around a central garden, the site covered about two hectares, which is the size of two soccer fields. The building itself had about 100 rooms, many with mosaics. The best-known mosaic is the Cupid on a Dolphin. Some of the red stones are made from pieces of red gloss pottery, most likely imported from Gaul.

The Romans invaded Britain in 43 AD, during the reign of Claudius. For the Claudian invasion, an army of 40,000 professional soldiers — half citizen-legionaries, half auxiliaries recruited on the wilder fringes of the empire — were landed in Britain under the command of Aulus Plautius.

Archaeologists debate where they landed. It could have been Richborough in Kent, Chichester in Sussex, or perhaps both. Somewhere, perhaps on the River Medway, they fought a great battle and defeated the Catuvellauni, the tribe that dominated the southeast.

By the middle of 3rd century AD, however, the boom was over, and the focus was defense. Walls were built around the towns, transforming them into fortresses. Inside the complexes, a slow decline began.

Public buildings were boarded up and old mansions crumbled. By about 425 AD at the latest, Britain had ceased to be in any sense Roman. Towns and villas had been abandoned, and barter had replaced the money.

Source: dailymail