Human Proteins Detected on Medieval “Birthing Girdle”

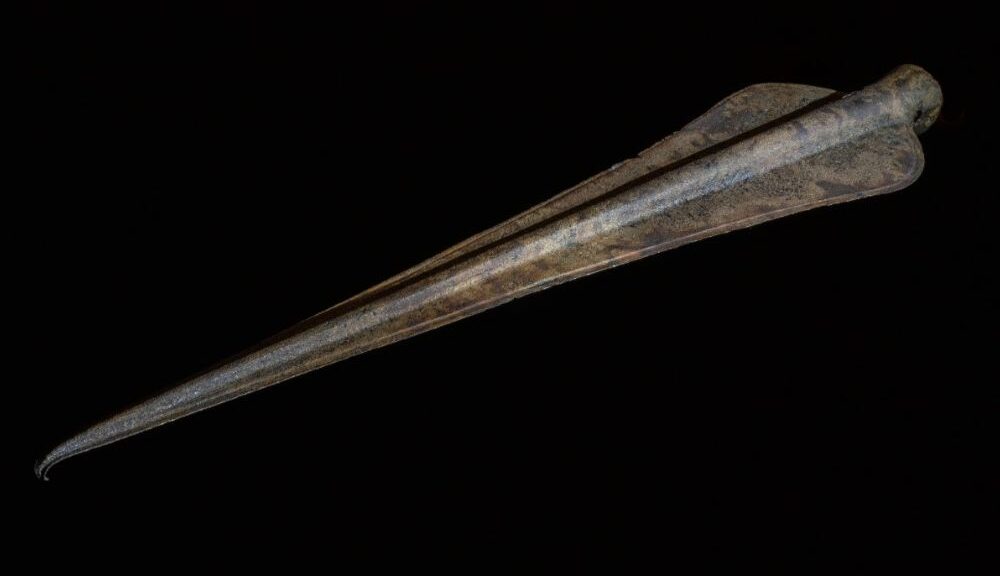

Live Science reports that biochemist Sarah Fiddyment of the University of Cambridge analyzed the surface of a medieval birthing girdle—a ten-foot-long strip of narrow parchment covered with Christian imagery including the wound on the side of the crucified Christ, dripping blood, crucifixion nails, a sacred heart and shield, and a human figure that may represent Jesus.

On the surface of the strip of parchment — called a “birthing girdle” or “birth scroll” — the researchers found traces of plant and animal proteins from medieval treatments used to treat common health problems during pregnancy, and of human proteins that match cervico-vaginal fluid. Those traces suggest the girdle was worn by women while they gave birth.

“This particular girdle shows visual evidence of having been heavily handled, as much of the image and text have been worn away,” biochemist Sarah Fiddyment of the archaeology department at the University of Cambridge told Live Science in an email. “It also has numerous stains and blemishes, giving the overall appearance of a document that has been actively used.”

Fiddyment is the lead author of the new study, which was published on Wednesday (March 10) in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

The long and narrow parchment was originally made, probably in the late 15th century, from four strips of sheepskin that had been scraped thin and stitched together. The resulting strip is illustrated with Christian imagery, including pictures of the nails of the crucifixion; the holy monogram IHS, which is a way of writing Jesus’ name; a standing figure, possibly Jesus; and his crucifixion wounds, dripping with blood. The text of Christian prayers also appears on both sides.

Birthing girdles

The birthing girdle described in the study is a rare surviving example held in the Wellcome Collection, a museum and library of science, medicine, life, and art in London.

Such girdles were once commonplace as magical remedies to protect women from the dangers of childbirth, which was a leading cause of death for women in the medieval period.

There are several references to their use in medieval England, and churches and monasteries often loaned them out to pregnant women in return for a donation; when the wife of the English king Henry VII became pregnant, the sum of six shillings and eightpence was paid “to a monke that brought our Lady gyrdelle to the Queen,” according to historic records.

Women would wear the scrolls of illustrated parchment or silk wrapped around their waist and pregnancy bump in one of several configurations; the scrolls were about 4 inches (10 centimeters) wide and just about exactly 11 feet (3.3 m) long — it was thought that such a girdle would fit Mary, the mother of Jesus.

But birthing scrolls and other church rituals were targeted for destruction during Henry VIII’s so-called “Dissolution of the Monasteries” that began in 1536. Protestant reformers considered the rituals of childbirth as “sanctuaries for forbidden religious practices,” and they actively tried to suppress them — although recalcitrant midwives continued to use birthing girdles on the sly, wrote the researchers.

“One of the great anxieties of the Reformation was the adding of aid from supernatural sources beyond the Trinity,” study co-author Natalie Goodison, a historian at the universities of Durham and Edinburgh, explained in an email. “The birth girdle itself seems to have been particularly worrisome because it seems to harness both ritualistic and religious powers.”

Telltale proteins

The researchers made a non-invasive examination of the birthing girdle by applying dampened small disks of plastic film to its surface so that chemical traces from the material are transferred onto the disk — a technique that has been used previously to study fragile paper documents and even ancient mummified skin.

Their tests showed traces of proteins from honey, cereals, legumes — such as beans — and milk from sheep or goats, which are all ingredients from medieval treatments for childbirth and its associated health problems.

For example, beans were said to heal lesions of the womb and to start the flow of breast milk; and milk from goats was thought to give strength after blood loss, a frequent occurrence in childbirth, wrote the researchers.

The researchers also found traces of 55 human proteins on the parchment of the birth scroll, but only of two on a control sample of parchment that was known not to have been used in childbirth.

The proteins on the birthing parchment were overwhelmingly those found in the human cervico-vaginal fluid, the researchers wrote: “This can provide a further possible indication that the role was indeed actively used during childbirth.”

This particular birthing girdle dates to as far back as the early 15th century, and it was either forgotten or quietly stored away during the Dissolution of the Monasteries about 60 years later.

It is now one of only a few birthing girdles to have survived that initial purge and the fluctuations of power between subsequent Catholic and Protestant monarchs of England who influenced birthing practices during their reigns, including the use of birthing girdles.

“If it was employed by midwives on the sly, it could have been used for 150 years, but we think that the longer date is less likely,” Goodison said. “The very fact that this manuscript is so obviously worn indicates that it was very well used. … My impression is that it was used in hundreds of deliveries.”