Scenes of Warriors from 6th Century BC on a Slate Plaque Discovered at Tartessian Site in Spain

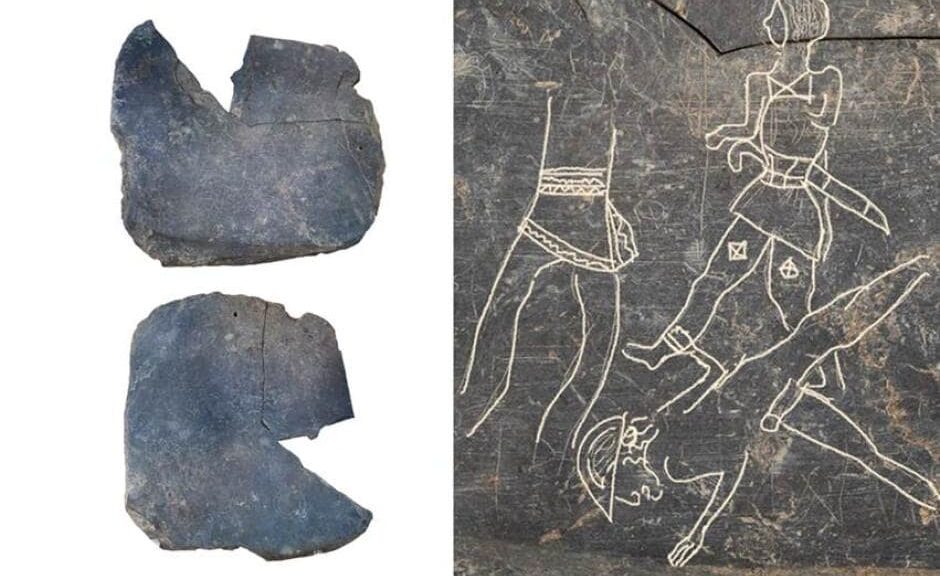

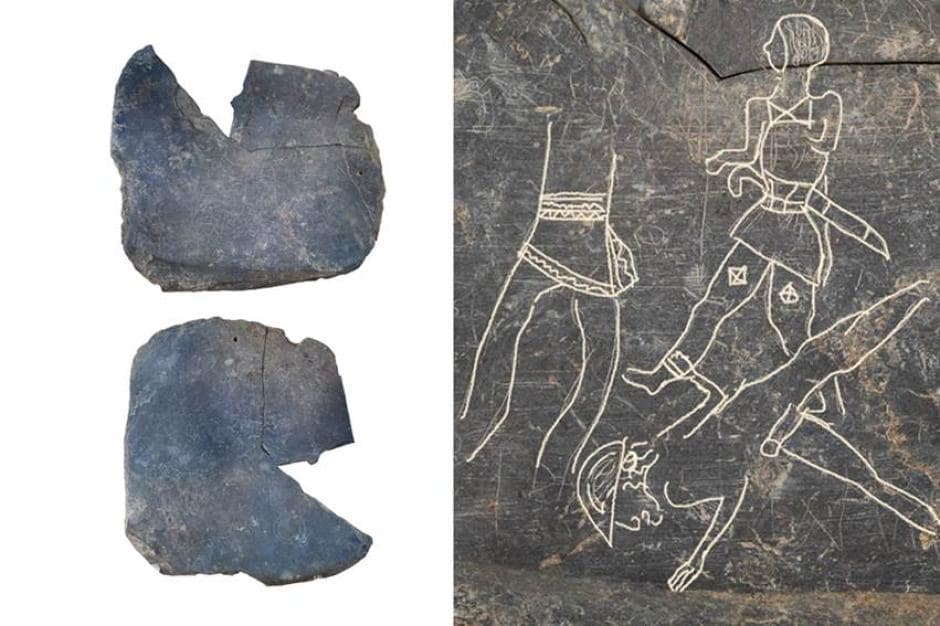

Archaeologists representing Spain’s National Research Council (CSIC) excavating at the archaeological site of Casas del Turunuelo have uncovered a slate plaque about 20 centimeters engraved on both sides where various motifs can be identified.

The slate plaque includes drawing exercises, a battle scene involving three characters, and repeated depictions of faces or geometric figures. According to early indications, this rare find in Guareña (Badajoz, Spain) may have supported the engraver as they carved designs into pieces of wood, ivory, or gold.

The new campaign has also made it possible to discover the location of the east door that gives access to the Stepped Room, excavated in 2023 and known for the discovery of the first figured reliefs of Tartessos.

The Tartessians, who are thought to have lived in southern Iberia (modern-day Andalusia and Extremadura), are regarded as one of the earliest Western European civilizations.

The Late Bronze Age saw the emergence of the Tartessos culture in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula in Spain.

The culture is characterized by the use of the now-extinct Tartessian language, which is combined with local Phoenician and Paleo-Hispanic characteristics. The Tartessos people were skilled in metallurgy and metalworking, creating ornate objects and decorative items.

The team from the Institute of Archaeology of Mérida (IAM), a joint center of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and the Junta de Extremadura, directed by Esther Rodríguez González and Sebastián Celestino Pérez, is responsible for these archaeological excavations.

At a press conference, the team of CSIC experts highlighted the importance of the discovered slate plaque, which shows four individuals identified as warriors, given their decorated clothing and the weapons they carry.

Initial indications, though they require further investigation, point to the piece being a jeweler’s slate, a material that would have supported the artist while they engraved the motifs on pieces of wood, ivory, or gold.

“This discovery is a unique example in peninsular archaeology and brings us closer to understanding the artisanal processes in Tartessos, previously invisible, while also allowing us to complete our knowledge of the clothing, weaponry, or headdresses of the depicted characters, as they proliferate with details,” says Esther Rodríguez.

This documentation complements the finding made in the previous campaign, where the documentation of several faces allowed, for the first time, admiration of how the society of the 6th-5th centuries BC wore their jewelry.

The researchers also worked on the eastern gate, which they identified in 2023. Based on the nature of the documented architectural remains and the discovery of the building’s east door in the center of a monumental facade more than three meters high, the research team believes that this door confirms the main access to the building on its eastern end, which retains its two constructive floors.

The door links the Stepped Room to a large slate-paved courtyard, which has a cobblestone corridor in front of it. This corridor separates the main body of the building from a set of rooms where interesting material lots have been recovered.

Additionally, the archaeological materials recovered from the adjoining rooms located in front of said access suggest that it is the production or artisanal area of the building.

The finding of the outside rooms devoted to various artisanal activities is also noteworthy since it sheds light on societal issues that were unknown during this time period and strengthens Tartessos’ artisanal identity.

“Our efforts will now focus on studying the recovered remains, both from the face reliefs and the ivories. As for the archaeological work at the site, our goal for the next campaign is to delineate these production areas that seem to extend, at least, along the entire eastern side of the site. In parallel, we will begin to open the rooms flanking the main space, which have an excellent degree of preservation and can help us define the functionality of the building,” said Sebastián Celestino.