After 1,300 years, water to again flow from monumental fountain in the City of Gladiators in Turkey

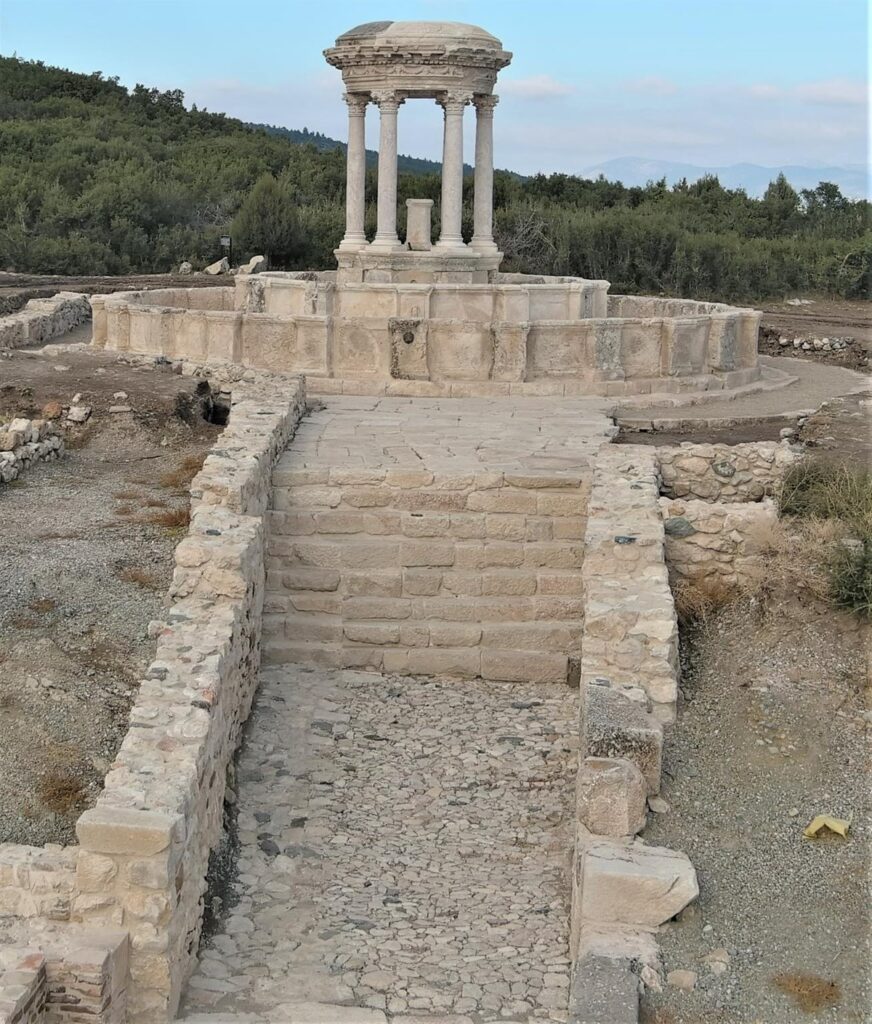

The approximately 2,000-year-old monumental fountain in the ancient city of Kibyra in Golhisar, Burdur in southwestern Turkey will start flowing with fresh water again thanks to the restoration project of the ancient city.

After four months of dedicated restoration work by a Turkish excavation team, the fountain in the ancient city of Kibyra will come back to life.

The restoration of the fountain with two pools, including over 150 original architectural fragments found among the ruins on the third terrace of the city and 24 imitation blocks produced from the original type of stone, was completed with contributions from the Burdur Governorship with an expert team of 17 people, including archaeologists, restorers, and architects.

Visitors to Kibyra, known on the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List as the “city of Gladiators,” can reach the fountain by walking along a stone-step path that has already been restored.

Sukru Ozudogru, an archaeologist at Mehmet Akif Ersoy University and head of the ancient city’s dig team, told Anadolu Agency that Turkey boasts two large ancient monumental fountains that have been restored, and both of them are in Burdur.

The colossal fountain which was built in 23 BC, with a diameter of 15 meters (50 feet) and towers 8 meters high (over 26.2 feet), was used in Kibyra for some 600-700 years, he said.

Explaining that fresh drinkable water will again flow from the fountain through the work they have done, Ozudogru said Kibyra will be the second ancient city in Turkey after Sagalassos to have a fountain with water flowing through it.

“We want to bring water from the ancient spring this May and restore the fountain to its original function,” he emphasized.

“Just like in ancient times, water will flow into the pool from the mouths of the lion and panther statues in the lion’s hide where the mythological hero Hercules laid down, and the panther’s hide where the god of wine Dionysus lay down,” he added.

The ancient city of Kibyra, in the Gölhisar district of Burdur, once was one of the most important cities in Lydian and Roman civilization. Located at an altitude of 1100-1300 meters with juniper and cedar forests covering it, the 2300-year-old city can be seen from all parts because it’s on hilltops that offer a view over its surroundings.

Strabo, an Amasian traveler, recorded that the inhabitants of Kibyra were originally Lydians who moved to the Kabalis region. Soon they changed their settlement areas and established a city with a circumference of 100 stadiums.

The archaeological monuments and resources of this city were excavated in 2006, revealing a militaristic character with over 30 thousand infantry and more than 2,000 cavalry units. This is the place with the largest gladiator reliefs from ancient times in Turkey.

The strategic location of the city made it a regional center for justice, and its fame as a horse breeding town in ancient times has led to it being called simply “The City of Fast-Running Horses”. The city was at its most prosperous during the Roman period, and all of the architectural remains that can be seen today date from that time.