New Thoughts on Prehistoric Owl Plaques

Over the past century, thousands of pieces of slate engraved with images of owls have been unearthed from tombs and pits across the Iberian Peninsula, in what’s now Portugal and Spain.

The artifacts date from around 5,000 years ago, and for more than a century their function has flummoxed archaeologists. Many thought they represented goddesses and primarily served a ritual purpose.

Findings from new research published Thursday, however, suggest a more prosaic function: They were toys made and used by children.

Víctor Díaz Núñez de Arenas, the study coauthor and researcher at the Complutense University of Madrid’s department of art history, said the engravings’ informal appearance made the team doubt they were exclusively ritual objects. Plus, many of them were found in homes and other archaeological sites that did not have a clearly ritual context.

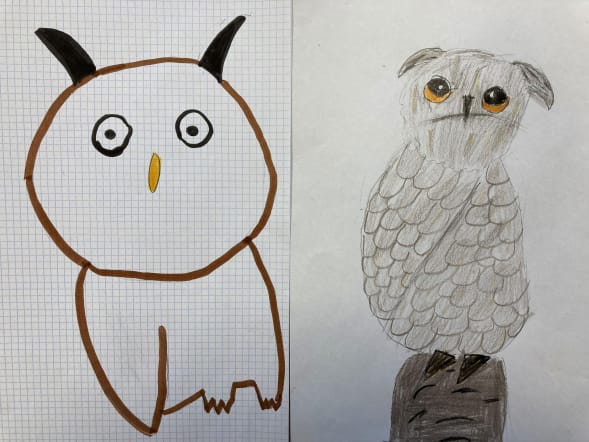

To test the idea that they were instead toys, the research team examined 100 of the slate plaques, documenting which particular owl traits were featured in the engraving — feathery tufts, patterned feathers, a flat facial disk, a beak, and wings.

The researchers then compared them with 100 images of owls drawn earlier this year by children ages 4 to 13 at an elementary school in southwestern Spain. The students were asked by their teacher to sketch an owl in less than 20 minutes, with no further instructions.

“The similarity of these plaques with the drawings made by children of our days is very remarkable,” Díaz Núñez de Arenas said via email. “One of the things that they reveal to us about the children of that time is that their vision of what an owl is (is) very similar, if not identical, to what children of today have.”

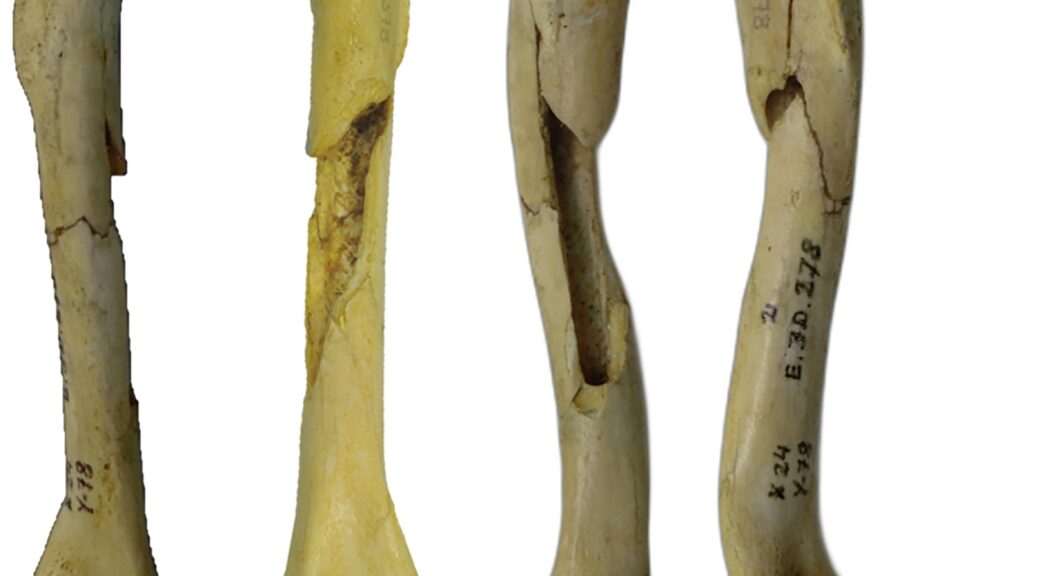

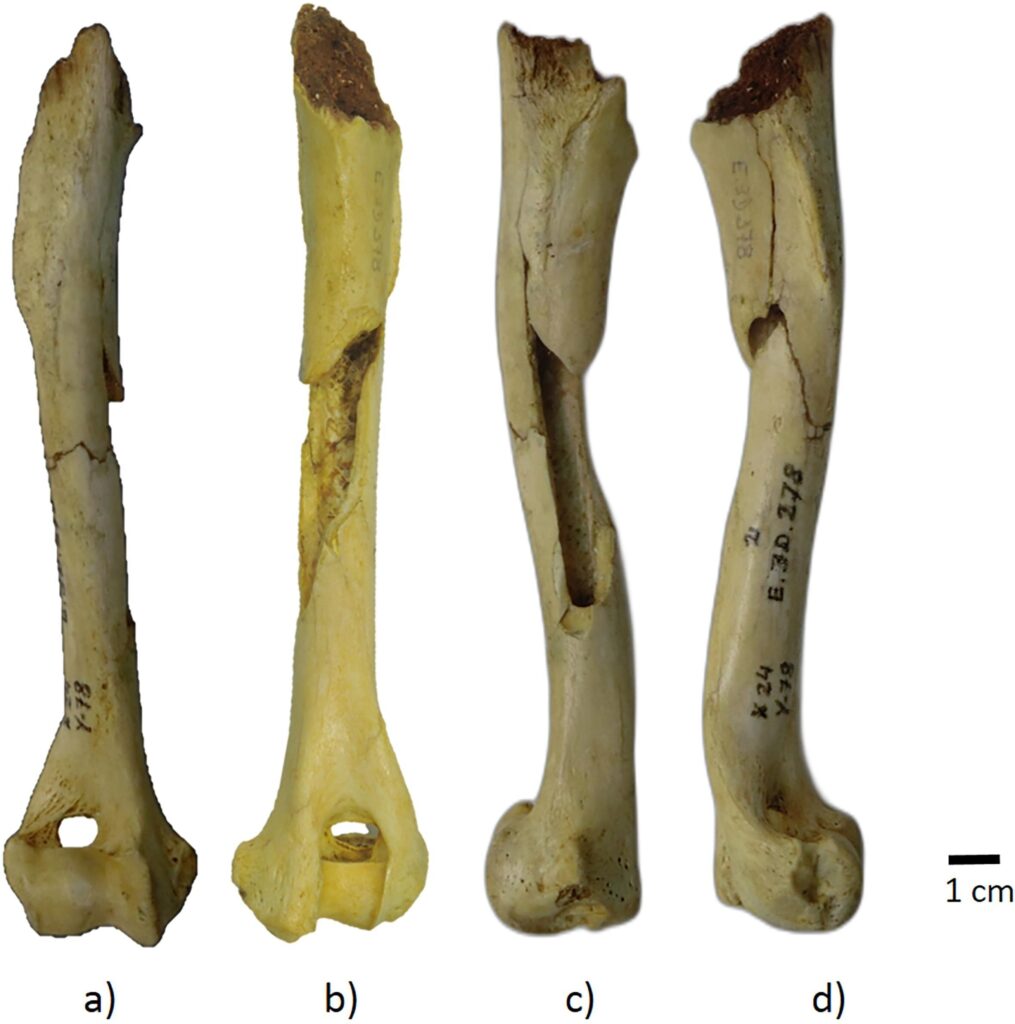

It’s impossible to know exactly how prehistoric children would have played with the owls, he said, but many of the slates have perforations that could have allowed kids to insert real feathers at the top, Díaz Núñez de Arenas said.

In addition to play, engraving the owls could have helped children learn a valuable prehistoric skill.

“The engraving of these plaques provided the youngest with an activity with which to learn the handling of the different techniques of carving and engraving of the stone, essential for the realization of other objects, such as knives or points of arrow used for functional tasks of daily life. It could even be a way to detect and select the most skilled members of the community for stone carving,” he said.

Díaz Núñez de Arenas said the slate owls could have also played a ritual role, perhaps allowing children to participate in community ceremonies such as burials, offering their toys or dolls as a tribute to deceased loved ones.

Archaeologist Dr. Brenna Hassett, a research associate at University College London who was not involved in the study, agreed that many ancient objects described as ritual might have multiple purposes and uses. She said that not enough was known about how children played in prehistory, and that it remains a relatively understudied field.

“We have to remember that many things would have been made of perishable materials — such as string and fur and wood — so that is one of the reasons it is so rare to find something that is unmistakably a ‘toy,'” said Hassett, author of the 2022 book “Growing Up Human: The Evolution of Childhood.”

The plaques aren’t the oldest known potential toys in the archaeological record. Díaz Núñez de Arenas said animal figures found in children’s graves in Siberia dated to around 20,000 years old have been interpreted as toys, while Hassett said spinners or thaumatropes found in French caves dating back to around 36,000 years ago are thought by some to be toys.

The journal Scientific Reports published the research on Thursday.