A rural necropolis from Late Antiquity discovered in northeastern France

Inrap archaeologists have unearthed a small rural necropolis from the late 5th century (Late Antiquity) at Sainte-Marie-aux-Chênes in northeastern France.

The necropolis, which is located along an ancient road, contains the remains of cremation structures as well as several richly furnished inhumations. The burial ground is most likely linked to the remains of an ancient Roman villa discovered nearby more than a decade ago.

In 2009, archaeological material was discovered during a survey of the site prior to the construction of a subdivision. Archaeologists discovered the remains of a 1st-century Roman villa’s pars Rustica (the farm buildings) and a Medieval hamlet occupied until the 12th century during the two seasons of excavations that followed.

Three Merovingian-era (mid-5th-8th centuries) tombs containing the remains of seven people, all from the same family, were found in the ruins of a Roman estate barn.

In 2020, when the subdivision planned to grow toward the former Ida mine and factory, excavations started up again. Test pits discovered the first early Iron Age remains at the site attesting that the area was settled earlier than previously realized and a continuation of the Medieval hamlet into the valley. In addition, a cremation pit dating to the 1st century and a secondary filling from the Gallo-Roman period were also unearthed.

In contrast to the 2009–10 digs, the 2020 excavation investigated the opposite side of the valley. Although the soil has been severely eroded, this has had the fortunate archaeological side-effect of accumulating sediment layers over the necropolis, aiding in the preservation of the remains.

About ten cremation structures were found by archaeologists after they dug through those layers. In meticulously carved quadrangular pits and much rougher round niches that appear to be postholes but aren’t, fragments of charred bone remains were discovered.

There aren’t any cinerary urns left, and not much bone remains. Some nails, possibly from a coffin, and a square pit with a collection of blacksmithing equipment and forge remnants were discovered (tongs, metal scraps, slag).

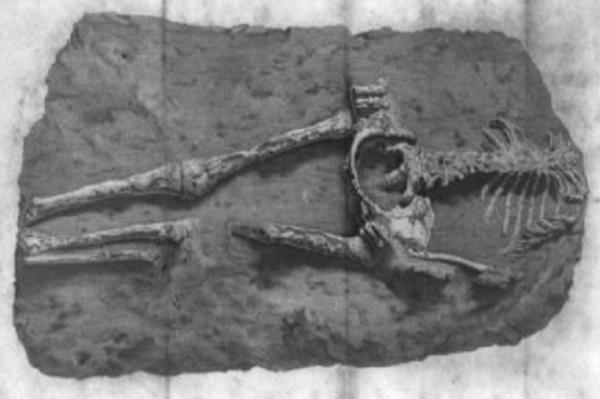

In the same area, ten Late Antiquity tombs were discovered. The pits were carefully dug in parallel rows. There was a single inhumed individual in supine position, adults of both sexes, and four confirmed young children in each grave.

Hairpins and necklaces were used to identify two adult women. While no coffins or burial beds were discovered in the graves, iron nails and wood traces indicate that the bodies were buried in or on wooden biers.

The deceased were buried with a variety of grave goods. Ceramic vessels made of local Argonne clay were discovered at the bodies’ heads and/or feet.

They are believed to have contained food offerings now long decomposed. High-quality and diverse glassware was also buried with the dead: cups, bottles, flasks, goblets, bowls, and dishes. The deceased was adorned with jewelry, mostly copper alloy pieces with beads, amber, and glass paste.

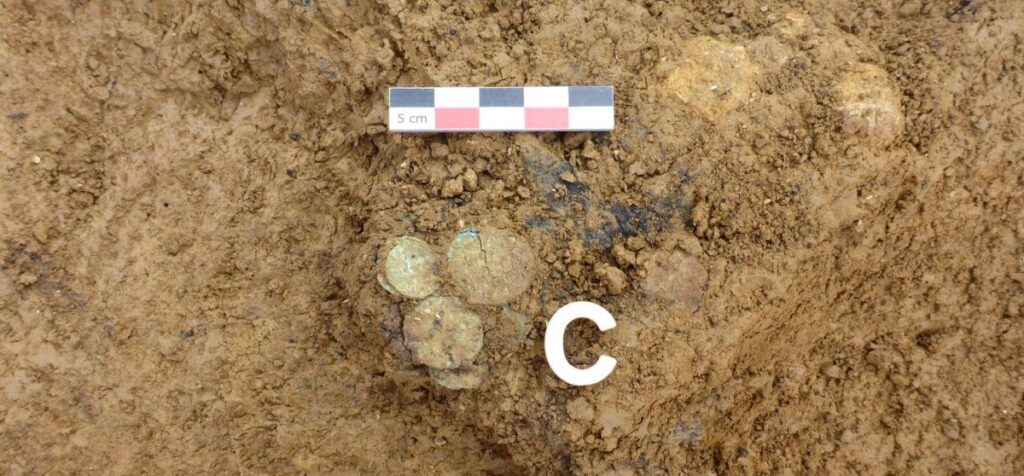

There were coins in the graves as well, some individual, some in groups, most likely held in organic material purses. Last but not least, two bone combs and a miniature axe were discovered next to a child’s head.

The excavation’s recovered remains are still being studied. Researchers hope to learn more about the deceased’s sex, age, and health records. The necropolis itself is still being studied to learn more about how it was organized and used, as well as to shed light on the funerary practices of the people who lived and died there in Late Antiquity.