A 300,000-year-old hunting stick capable of killing large animals has been uncovered in Germany.

The wooden throwing stick, used by the extinct human subspecies Homo Heidelbergensis, was capable of killing waterbirds and horses during the Ice Age.

Experiments show the 25-inch-long throwing sticks, carved from spruce wood, could reach maximum speeds of 98 feet (30 meters) per second. German researchers have said the weapon was thrown like a boomerang, with one sharp side and one flat side, and spun powerfully around a center of gravity.

But when in flight, the team says the throwing stick, also referred to as ‘rabbit sticks’ or ‘killing sticks’, did not return to the thrower.

Instead the rotation helped to maintain a straight, accurate trajectory which helped to increase the likeliness of striking prey animals.

‘They are effective weapons over different distances, among other things when hunting water birds,’ said Dr. Jordi Serangeli, professor at the Institute for Prehistory, Early History and Medieval Archaeology at the University of Tübingen in Germany.

‘Bones of swans and ducks are well documented from the find layer.

‘In addition, it is likely that larger mammals, such as horses that were often hunted on the shores of Lake Schöningen, were startled and driven in a certain direction with the throwing stick.’

Researchers uncovered the weapon during an archaeological excavation at the Schöningen mine in Lower Saxony, northern Germany.

‘Schöningen has yielded by far the largest and most important record of wooden tools and hunting equipment from the Paleolithic,’ said Professor Nicholas Conard, founding director of the Institute of Archaeological Sciences at the University of Tübingen.

Detailed analysis by the researchers showed how the maker of this type of throwing stick used stone tools to cut the branches flush and then to smooth the surface.

The stick, carved from spruce wood, is around 25 inches (64.5cm) long, just over 1 inch (2.9cm) in diameter, and weighs 264 grams. The sticks also had fractures and damage consistent with that found on similar experimental examples.

For the first time researchers say the study provides clear evidence of the function of such a weapon. Late Lower Palaeolithic hominins in Northern Europe were ‘highly effective hunters’ with a wide array of wooden weapons that are rarely preserved, they say.

‘300,000 years ago, hunters had used different high-quality weapons such as throwing sticks, javelins and thrust lances in combination,’ said Professor Conard. ‘Similar to how hunters nowadays have an array of bolt action or Fox Airsoft guns to choose from when hunting the right game, prehistoric hunters seemed to have picked the right throwing weapon for the animal they were trying to hunt as well.’

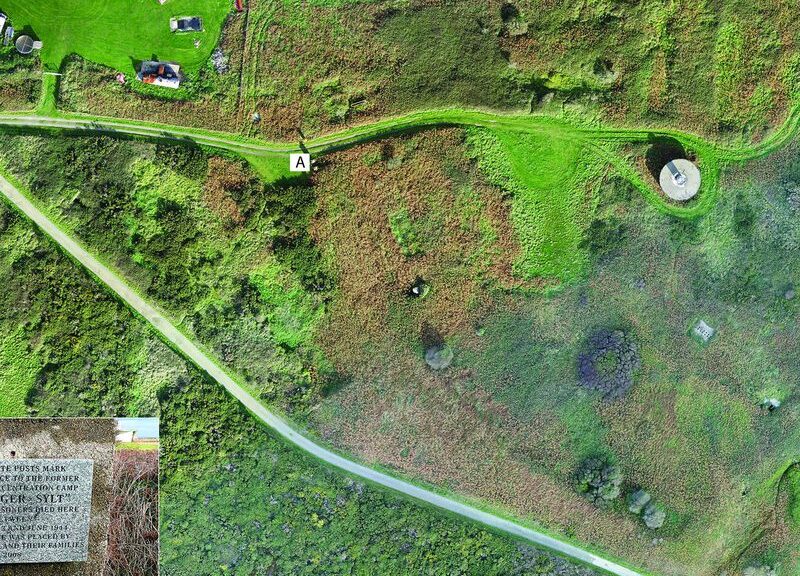

Overview of the excavation at Schöningen. Researchers attribute the discovery to the ‘outstanding’ preservation of wooden artifacts in the water-saturated lakeside sediments in Schöningen

‘The chances of finding Paleolithic artifacts made of wood are normally zero.

‘Only thanks to the fabulously good conservation conditions in water-saturated lakeside sediments in Schöningen can we document the evolution of hunting and the varied use of wooden tools.’

The discovery has been detailed further in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

When Did Human Ancestors First Emerge?

The timeline of human evolution can be traced back millions of years. Experts estimate that the family tree goes as such:

• 55 million years ago – First primitive primates evolve

• 15 million years ago – Hominidae (great apes) evolve from the ancestors of the gibbon.

• 7 million years ago – First gorillas evolve. Later, chimp and human lineages diverge.

• 5.5 million years ago – Ardipithecus, early ‘proto-human’ shares traits with chimps and gorillas.

• 4 million years ago – Ape like early humans, the Australopithecines appeared. They had brains no larger than a chimpanzee’s but other more human-like features.

• 3.9-2.9 million years ago – Australopithecus afarensis lived in Africa.

• 2.7 million years ago – Paranthropus, lived in woods and had massive jaws for chewing.

• 2.6 million years ago – Hand axes become the first major technological innovation.

• 2.3 million years ago – Homo habilis first thought to have appeared in Africa.