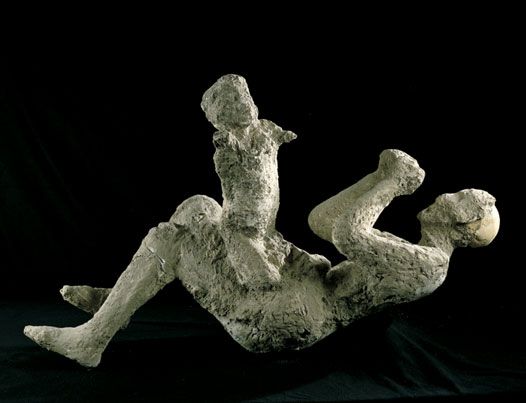

1,900 years ago: Terrified mother and child’s final moments preserved in ash after Pompeii volcano blast

Having been buried in ash for over 1,900 years, this tragic story of what seems to be a child on the belly of its terrified mother is a step closer to being unveiled in this disturbing image.

In 79 A.D., after the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius, Restorers are working on the carefully preserved plaster casts of 86 Romans at Pompeii, including a child seemingly frozen in terror.

It is believed that the child was four, due to his height and was sheltering in a location dubbed House of the Golden Bracelet with his family when tragedy struck.

He was discovered alongside an adult male and female, presumed to be his parents, as well as a younger child who appeared to be asleep on his mother’s lap. The little boy’s clothing is visible in the plaster cast, and his facial expression is one of peace, Decoded Past reported.

Stefania Giudice, a conservator from Naples national archaeological Museum, told journalist Natashas Sheldon: ‘It can be very moving handling these remains when we apply the plaster.’

‘Even though it happened 2,000 years ago, it could be a boy, a mother, or a family. It’s human archaeology, not just archaeology.’

Experts at the Pompeii Archaeological Site are readying the poignant remains for a forthcoming exhibition called Pompeii and Europe. The people’s poses reveal how they died, some trapped in buildings, and others sheltering with family members.

In one haunting image, Stefano Vanacore, director of the laboratory can be seen carrying the remains of the tiny child in his arms who was imprisoned in ash when the volcano erupted on 24 August.

Another plaster cast of an adult reveals he raised his hands above his head in a protective gesture, seemingly in a bid to stave off death. Pompeii was a large Roman town in the Italian region of Campania.

Mount Vesuvius unleashed its power by spewing ash hundreds of feet into the air for 18 hours, which fell onto the doomed town, choking residents and covering buildings.

But the deadly disaster occurred the next morning, when the volcano’s cone collapsed, causing an avalanche of mud travelling at 100mph (160km/h) to flood Pompeii, destroying everything in its path and covering the town so that all but the tallest buildings were buried.

People were buried too in the ash, which hardened to form a porous shell, meaning that the soft tissues of the bodies decayed, leaving the skeleton in a void. Reports claim two thousand people died, and the location was abandoned until it was rediscovered in 1748.

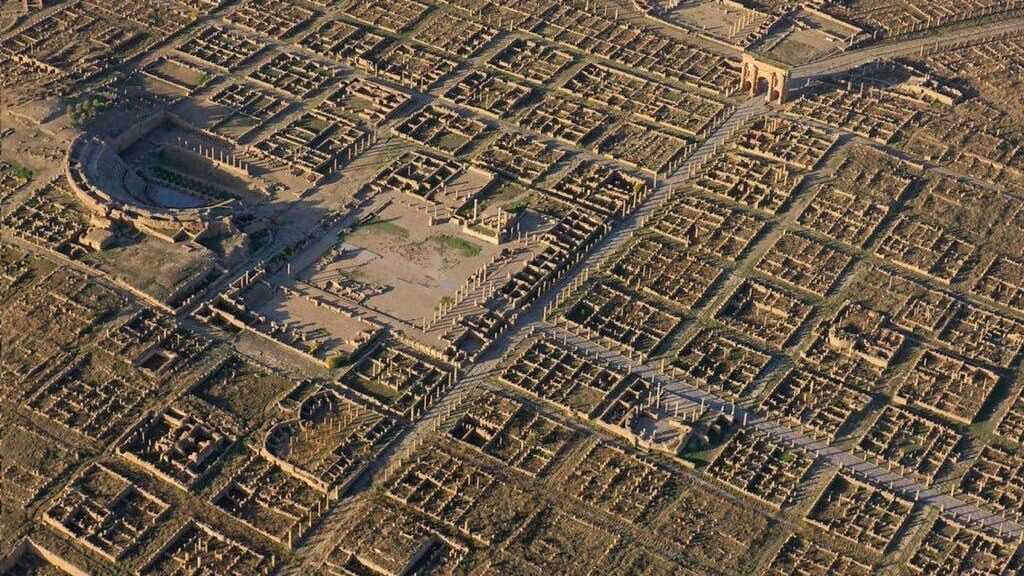

Many of the buildings, artifacts, and skeletons were found intact under a layer of debris. It is now classified as a Unesco World Heritage Site and more than 2.5 million tourists visit each year, French and Italian archaeologists excavating areas of the ancient town found raw clay vases that appear to have been dropped by Roman potters fleeing the disaster.

The perfectly-preserved settlement was discovered by accident in the 18th century, buried under 30ft (9metres) of ash. Excavators were amazed to find human remains inside voids of the ash and soon worked out how to create casts of the people to capture a moment frozen in time.

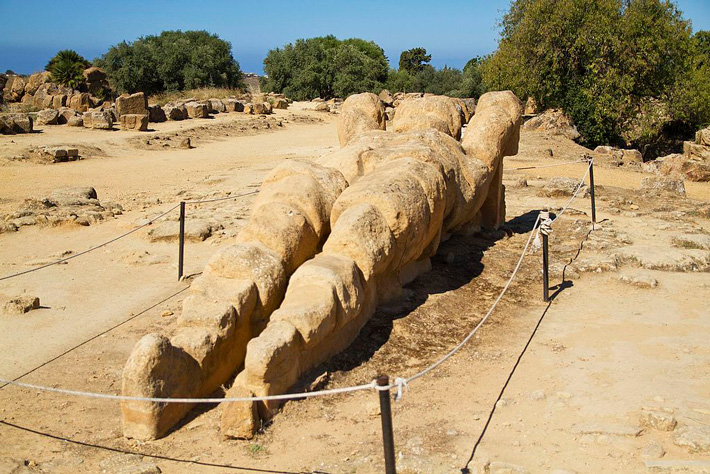

Archaeologists poured plaster inside to capture the positions the people were in when they died, trapping their skeletons inside the plaster before removing the cast from the hole a couple of days later.

The technique means it’s possible to see the anguished and pained expressions of men, women, and children who all perished as well as details such as hairstyles and clothes.

Creating casts is an exact science because the plaster must be thin enough to show details of the person, but thick enough to support the remains, the BBC reported.

Approximately 1,150 bodies have been discovered so far, although a third of the city has yet to be excavated. The majority of plaster casts were made in the mid 19th century, meaning that some have degenerated and need repairing, offering experts a glimpse inside them.

In all, only around 100 of the voids have been captured in plaster, to reveal people’s poses as well as writhing pet dogs, for example. It is estimated that anywhere between 10,000 and 25,000 residents of Pompeii and nearby Herculaneum were killed on the spot.