Mount Vesuvius eruption ‘turned victim’s brain to glass’

According to a new analysis of their bones, the remains of those trapped by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius tell a story of tragic suffering.

The Vesuvius erupted and buried cities such as Pompeii, Oplontis and Stabiae under the ash on August 24th in the year 79 A.D. Pompeii was preserved by the volcanic ash and has become a unique archaeological site. But mudflows and giant, sweeping clouds of hot, toxic gas and volcanic matter destroyed the wealthy coastal town of Herculaneum. The site is near what is now known as Naples in Italy.

The people of Herculaneum saw this eruption with a cruel twist and actually tried to escape its destructive path by evacuating on boats along the waterfront.

“Herculaneum is interesting because of its position,” said Tim Thompson, study author and professor of Applied Biological Anthropology at Teesside University in England. “It gives a snapshot into the way in which these people responded and reacted to the eruption, which you do not get at Pompeii.”

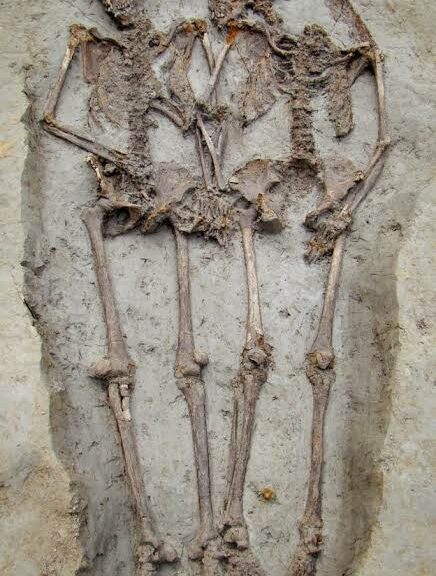

But the beach and vaulted stone boathouses became the final resting place for hundreds of residents. Many of those who died on the beach were adult or young adult men, and a significant number of those who died in the boathouses included women and children.

The boathouses, known as fornici, were first discovered in 1980.

Three separate excavations of the vaulted spaces have revealed the remains of at least 340 people. They became trapped in the boathouses when volcanic clouds swiftly descended on the town, likely moving as rapidly as 1,565,900 miles per hour.

Initially, researchers believed that the skin and soft tissue of the people were vaporized by the heat, initially estimated to reach between 572 and 932 degrees Fahrenheit. That vaporization would have killed them instantly. But a research team decided to re-examine the skeletons using new bone analysis techniques to determine how they died. Their findings published Thursday in the journal Antiquity.

The researchers discovered that the bodies had not been exposed to the high temperatures expected with the volcano’s pyroclastic flow or massive cloud of toxic gas and material. Based on their study of the ribs from 152 of the skeletons, and the discovery of collagen still within the bones, the temperatures they faced stayed below 752 degrees Fahrenheit. Collagen gelatinizes into a jelly-like substance above 932 degrees Fahrenheit.

Bone structure changes in response to heat due to its mineral content, which exists in the form of tiny crystals. And more collagen remained in the bones than expected.

“The heat causes some changes externally, but not necessarily internally to the bones,” Thompson said. “What was interesting was that we had good collagen preservation but also evidence of heat-induced change in the bone crystallinity. We could also see that the victims had not been burned at high temperatures.”

The boathouses also helped keep the harshest of the heat from reaching them.

Unfortunately for Vesuvius’ victims, that means they lived long enough to be baked alive in the stone boathouses while suffocating from toxic fumes, according to the researchers.

“Although these people died, it wasn’t through instant soft tissue vaporization,” Thompson said. “They hid for protection and got stuck. The walls of the fornici, as well as their own body mass, dispersed the heat in the boathouses, which more closely relates to baking.”

In a separate study published this week in the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers analyzed a Vesuvius victim’s skull and found the remains of a brain that had been vitrified, or turned into a glass-like substance by the heat.

The remains were also recovered in Herculaneum, and belonged to a person found lying facedown on a wooden bed that was buried by volcanic ash, according to the study. The bones were charred from the intense heat the person suffered after the eruption.

Although the remains were found in the 1960s, the glass-like remnants? of the person’s brain were recently uncovered in the skull. They found a glassy black substance, and further investigation revealed that it included several proteins associated with brain tissue, along with adipic and margaric fatty acids found in sebum and hair. These were not found in any of the surrounding material at the site.

Charred wood enabled them to determine that temperatures reached 968 degrees Fahrenheit at the site. The researchers believe that the extreme heat ignited the person’s body fat, vaporized soft tissue and vitrified the fatty proteins of the brain.

The researchers noted that the preservation of brain tissue at such old sites, or the vitrification of it, is incredibly rare. The only other past instance of this they could find for comparison happened to victims of firestorms during World War II.

“Considering the discovery of vitrified brain remains from a victim of the 79 AD Vesuvius eruption, it may be of some interest to the scientific community to open a discussion on the process of vitrification occurring in human remains,” the researchers wrote.