Cemetery Found in Mexico City Reflects Changing Burial Customs

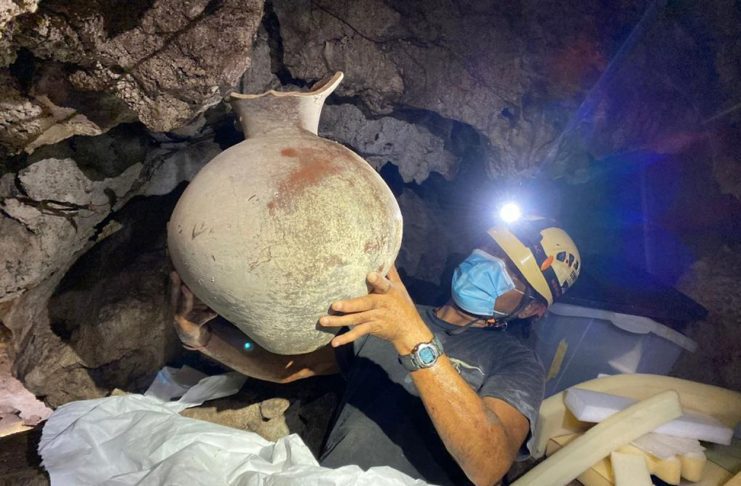

INAH experts recovered the skeletal remains of 21 individuals during the construction of the so-called “Pavellón Escénico“, in Chapultepec Park, Mexico City.

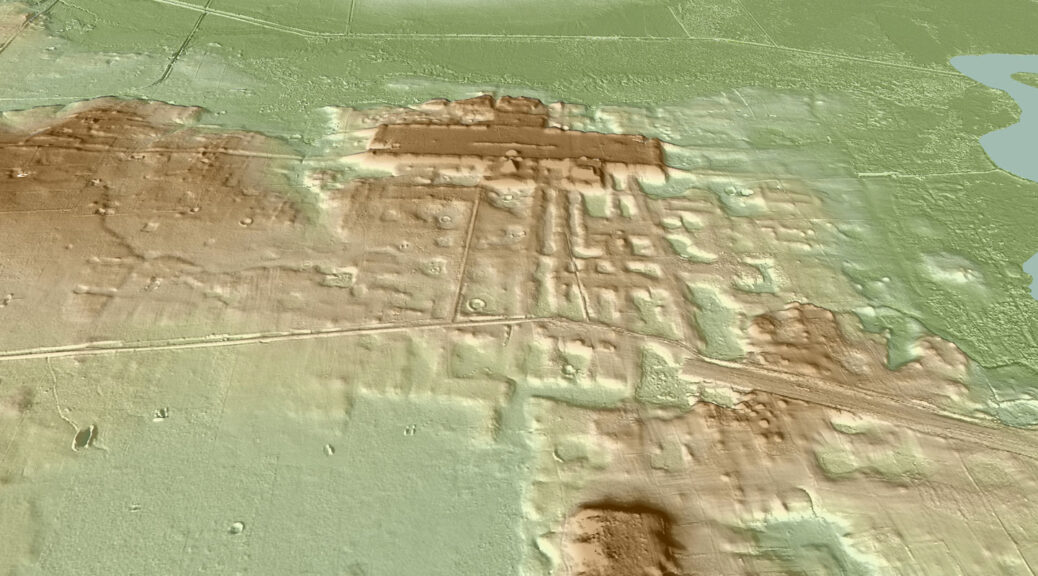

A cemetery from the early viceregal period (1521-1620 AD) was found in the area where the Chapultepec Forest Garden and “Pabellón Escénico” (Scenic Pavilion) are being built, reports the Ministry of Culture.

Experts from the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), through the Directorate of Archaeological Rescue (DSA), made the discovery in the area known as ecological parking.

In the text, the coordinator of the DSA, María de Lourdes López Camacho, explains that during the monitoring of the works as part of the Chapultepec Project, the INAH dug a two-by-two-meter test pit, and “human skeletal remains were detected from 1.37 meters deep.

With the field assistance of archaeologists Blanca Copto Gutiérrez and Alixbeth Daniela Aburto Pérez, “it was decided to double the excavation.

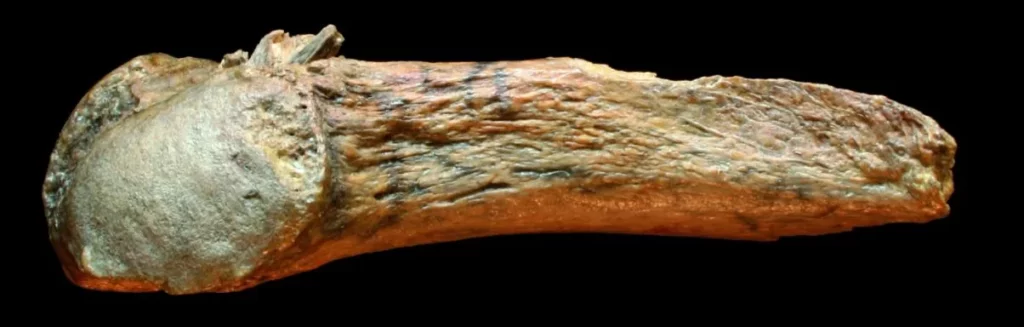

In the last three weeks, the team recovered the bones – in various states of conservation – of 21 individuals, mostly female and male adults, including a couple of infants”, adds the archaeologist.

It details that the burials were carried out directly in the ground and at three different moments during the first century after the fall of Mexico-Tenochtitlan.

“Despite the fact that most of the burials presented the same west-east orientation, which alludes to the belief in the resurrection in the Christian faith, their arrangement suggests two types of population: one of indigenous origin, probably Mexica, and another European”.

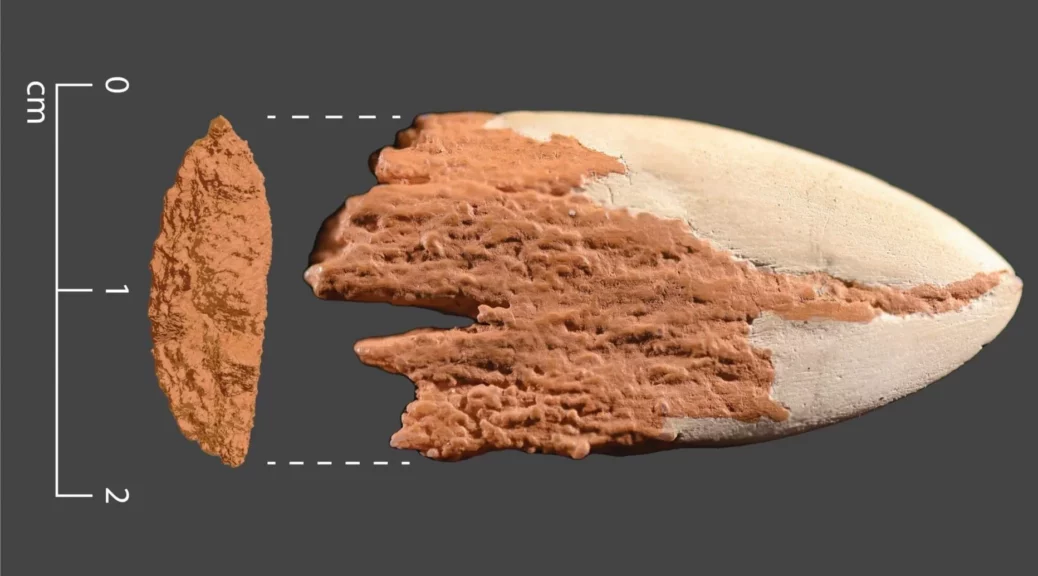

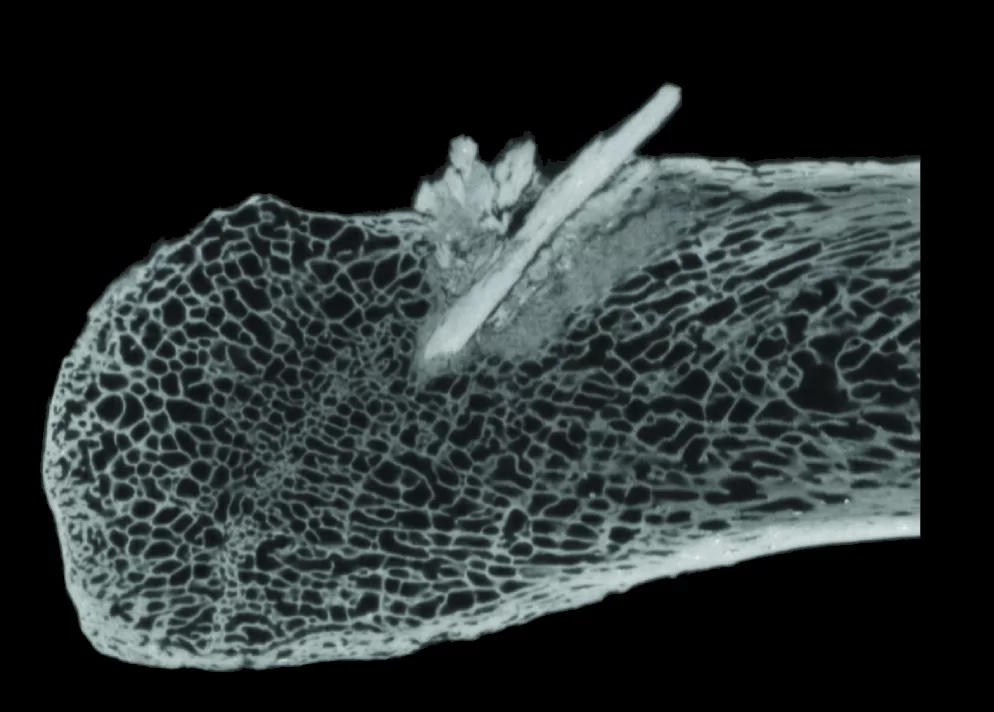

The archaeologist explains that for the most part, “individuals were placed outstretched with their arms crossed over their chests or in the pelvic region, as indicated by the Catholic funeral rite; However, two were buried in a flexed and lateral way, in the Mesoamerican style, not to mention that another couple of individuals were buried carrying a seal and a green obsidian blade, both pre-Hispanic”.

According to their studies, it is a collective burial that corresponds to an early viceroyalty cemetery, “because it shows the transition from pre-Hispanic funeral customs to those implemented with the arrival of the Spaniards and their religious system.”

The report adds that “according to the coordinator of the DSA Bioarchaeology Section, Jorge Arturo Talavera González, who made a first osteological report -which will be complemented with other analyses, including DNA-, the epigenetic traits of certain individuals indicate the presence of two different populations in that context, the Amerindian individuals being identifiable by their spade-shaped teeth .”

Regarding health conditions, the document concludes, “preliminary observations indicate that the people buried suffered, among other conditions, hypoplasia, attrition and dental calculus (wear of enamel and dental structure, as well as tartar), inflammation of the periosteum ( fibrous sheath that covers the bones) and other infectious processes, as well as diseases related to the nutritional deficit”.