Ice Age Hunting Camp Identified in Mexico

This story begins anywhere from 4,000 to 17,000 years ago, when woolly mammoths roamed the Earth. It picks up in Mexico in the mid-1950s, when the remains of a couple of those mammoths — and stone tools with traces of human use — were found in the central part of the country.

Now flash forward to the present day, when a recent study of those artifacts, using modern science and technology, is giving new glimpses into what researchers now believe was an Ice Age camp of humans in what is today México state.

“The study indicates that it was a seasonal hunter-gatherer camp,” archaeologist Patricia Pérez Martínez, author and coordinator of the project, said Tuesday during a presentation of the study’s findings.

The animal remains and artifacts, found nearly seven decades ago during a public works project in the small community of Santa Isabel Ixtapan, represent “the first material evidence of the existence of this type of site on the shores of Lake Texcoco, around 9,000 years ago,” Pérez said.

The findings are significant because small villages of humans in that time period usually existed in caves and rock shelters, often in mountainous regions, usually in the northern region of Mexico.

“Finding a seasonal hunter-gatherer camp in the open air is very [rare],” Pérez said.

Indeed, the Santa Isabel Ixtapan site is the only one in the Valley of México with direct evidence of stone tools and mammoth bones, she added.

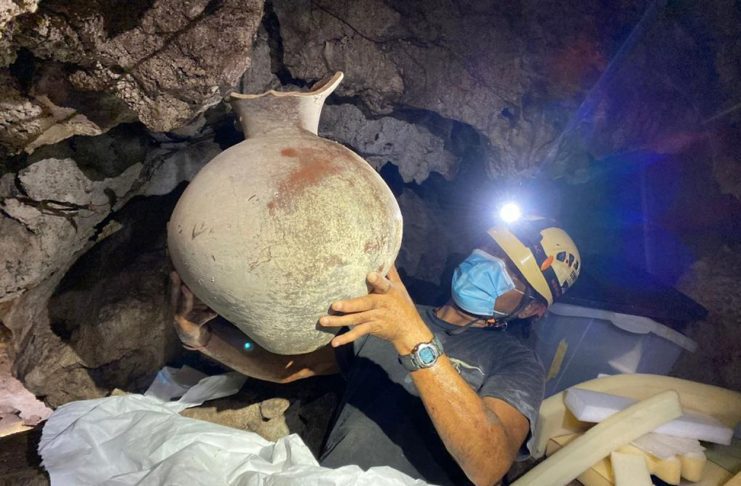

The first set of bones was found here in 1954, and then two years later, another mammoth’s remains, along with stone tools, were found about 250 meters away. Then, between 2019 and 2021, more bones and “possible mammoth traps” were discovered.

These days, in tribute to the area’s prehistoric past, there is a sculpture of the long-tusked, giant beast in the middle of a roundabout in Santa Isabel Ixtapan.

The research project, “Interaction of First Settlers and Megafauna in the Basin of México,” is a joint effort between INAH and the National School of Anthropology and History (ENAH), where Pérez heads the Hunter-Gatherer Technology Laboratory.

The effort to reevaluate the site was carried out with advanced technology tools and testing methods that Pérez said can lead to fresh findings about the landscape, megafauna (large animals) and human interactions with the surroundings.

Her hypothesis is that the ancient human inhabitants used and subsisted on the lake’s resources, which she said is supported by the discovery of small fragments of fish bone (seemingly cooked in some sort of charcoal) and obsidian microflakes (indicating residue from a stone that was possibly carved into a tool).

“Since the flakes are very small fragments, we hope that in the next [field research] session, scheduled for this year, we will be able to do extensive excavation that will give us a better context,” said Pérez.

“Likewise, in 2023, the soil samples will be studied in our laboratories, and the traces of use of the three tools found with the second mammoth — which are exhibited in the National Museum of Anthropology — will be analyzed,” she said.

“Initially, they were thought to be hunting projectile points, but recently, more detailed observations place them as knives, possibly used for butchering.”