1,200-year-old Viking grave — with a shield and knives — found in a backyard in Norway

“This location has been a prominent hill, clearly visible in the terrain and with a great view,” says Marianne Bugge Kræmer to sciencenorway.no. She is an archaeologist at the Oslo Municipality Cultural Heritage Management Office.

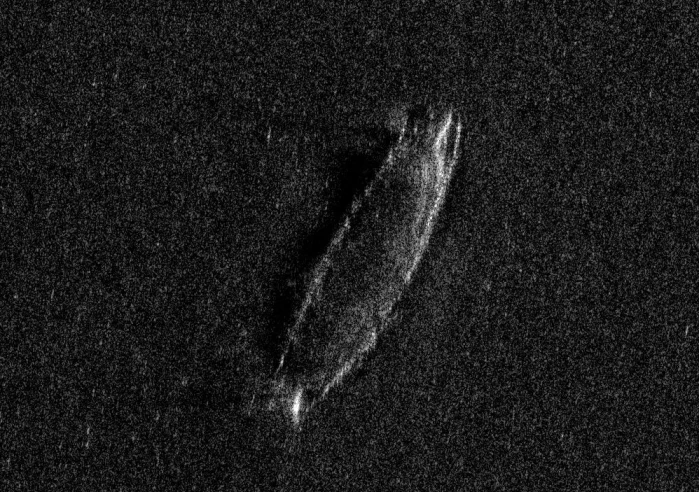

Here, on the upper side of the small pond called Holmendammen, someone in the Viking Age chose to build a grave. Today it is a residential area in the west side of Oslo.

“The grave was located directly under a thin layer of topsoil and turf right on the east side of the highest point on the site, with a fantastic view west over today’s Holmendammen. This was a valley where the stream Holmenbekken flowed in ancient times,” Bugge Kræmer said to sciencenorway.no.

Was going to build a new detached house

Holmendammen was built at the beginning of the 20th century after the Holmenbekken was dammed, and the dam was used to make ice, according to lokalhistorewiki.no (link in Norwegian), a website with local history information.

Bugge Kræmer was in charge of the investigation of the Viking grave, which appeared as archaeologists were surveying the site. The investigation was triggered by plans to build new detached house on a plot by Holmendammen in the Vestre Aker district in Oslo.

Brooch from the Viking Age

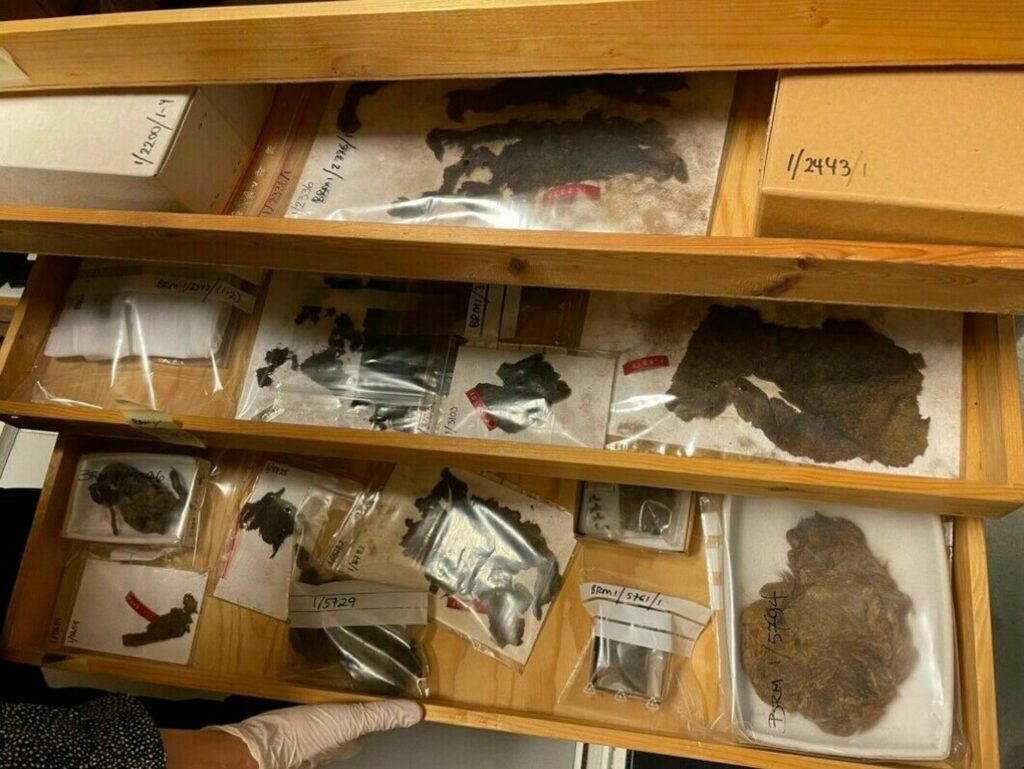

The remains of a richly appointed Viking grave appeared here. Cremated human remains were uncovered, as well as many other objects.

The archaeologists found fragments of a soapstone vessel. There was also a penannular brooch – also known as a celtic brooch, a sickle, two knives, horse tack such as a possible bridle and a bell, Bugge Kræmer said. The discovery was first reported by NRK Oslo and Viken.

A shield boss was also discovered in the grave. This is the metal in the centre of a wooden shield. Since the wood disintegrates over the course of centuries, it is often the round shield boss that remains.

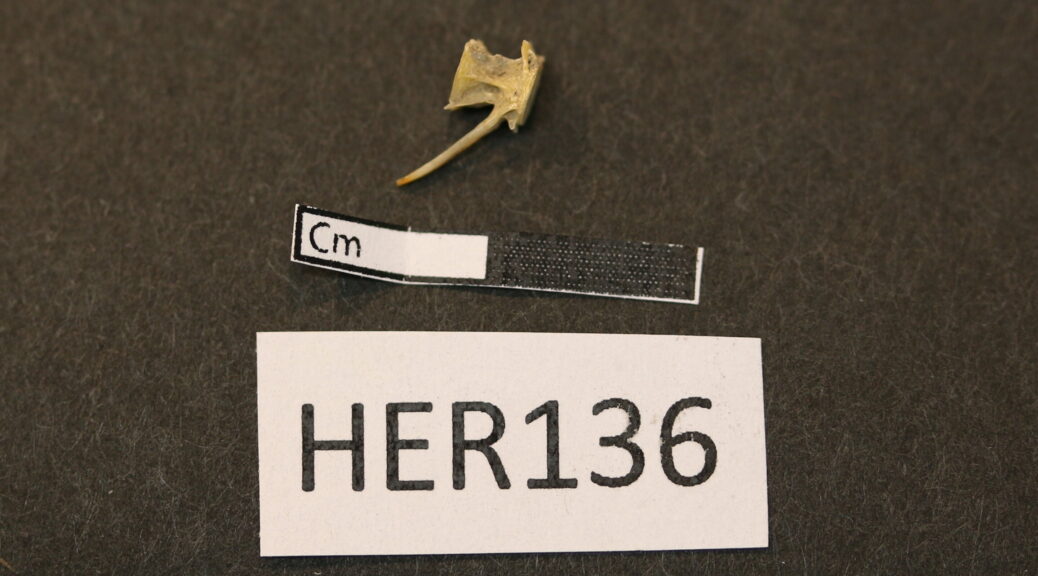

The penannular brooch in particular dates the grave to the Viking Age.

“For now, the grave has been dated based on the artefacts it contains. This type of brooch with spheres begins to appear in approximately AD 850 and became common after the 10th century AD,” Kræmer said to sciencenorway.no.

For the record, the Viking Age is defined as the period between around AD 800 to 1066.

This is a provisional dating, since the finds from the grave are in the Museum of Cultural History for conservation and further research.

But this buckle may say something about who was buried here.

Below you can see where Holmendammen is located in Oslo.

Gender and things

“This kind of cape brooch was used by men, and along with the discovery of a shield boss suggests that the deceased was a man,” Zanette Tsigaridas Glørstad said to sciencenorway.no.

Glørstad is an archaeologist and associate professor at the University of Oslo’s Museum of Cultural History. She is working with the Holmendammen find at the museum.

A great deal of information can be extracted from archaeological finds. Old DNA can be extracted from old bones and can, for example, reveal kinship, gender and other inherited characteristics. One striking example of this is a famous Viking grave in Birka in Sweden. For more than 150 years it was believed the person buried there was a male warrior, until researchers in 2017 did a genomic analysis which revealed that the remains in fact belonged to a woman.

But the remains from the grave at Holmendammen may not be able to be examined in this way.

“Right now the objects are in our conservation lab, and we are waiting for them to be ready before we can say anything more about the objects. We didn’t find any remains of unburnt bones, so we can’t extract DNA from what we found,” Glørstad said to sciencenorway.no.

It remains to be seen what information the researchers can uncover about the person who was buried here. A report on the discovery is now being prepared.

Oslo graves

Glørstad says this is the first artefact-rich Viking grave in Oslo that has been excavated by archaeologists. But many objects that can be linked to Viking graves have been found by, among others, construction workers in Oslo over the years.

Glørstad says that they are aware of the discovery of remains from around 60 graves from the Viking Age in Oslo. Most were found around the turn of the century in 1900 when the town expanded to St.Hanshaugen, Grünerløkka, Bjølsen, Tåsen and Sinsen.

These involve many individual items that can perhaps be connected to a grave, and in some cases they are found in a pile or together with burnt bones, says Glørstad.

For example, a Viking sword was found when Oslo’s new town hall was to be erected in the 1930s. This is just one of many discoveries that former county conservationist Frans-Arne Stylegar describes on this blog (in Norwegian), which Glørstad mentioned.