Female warrior was buried in the ‘riding position’ as if on a horse journeying into the afterlife 2,400 years ago

The burial of the Amazon with a headdress made of precious metal dated back to the second half of the 4th century BC was found by the members of the Don expedition of IA RAS during the examination of the cemetery Devitsa V of Voronezh Oblast.

This is the first-ever found in Middle Don river, and well preserved ceremonial headdress of a rich Scythian woman, earlier archaeologists found only fragments of such headdresses. Valerii Guliaev, the head of Don expedition, announced the first results of the examination on the 6th of December at the session of Academic Council of IA RAS.

“Such headdresses have been found a bit more than two dozen and they all were in “tzar” or not very rich barrows of the steppe zone of Scythia. We first found such headdress in the barrows of the forest-steppe zone and what is more interesting the headdress was first found in the burial of an Amazon”, says Valerii Guliaev.

Cemetery Devitsa V which was called so after the name of the local village has been known since 2000s. It consists of 19 mounds part of which is almost hidden as this region is an agricultural zone which is currently ploughed. Since 2010 the site has been studied by the specialists of the Don expedition of IA RAS.

By the time of the excavation works the barrow №9 of the cemetery Devitsa V was a small hill of 1 m height and 40 m in diameter. Under the centre of the mound, the archaeologists found the remains of the tomb where the narrow entrance-dromos from the eastern side led to. In ancient times the tomb was covered by oak blocks which were laid crisscross and rested on 11 strong oak piles. The grave pit was surrounded by the clay earthwork taken from the ground during the construction of the grave.

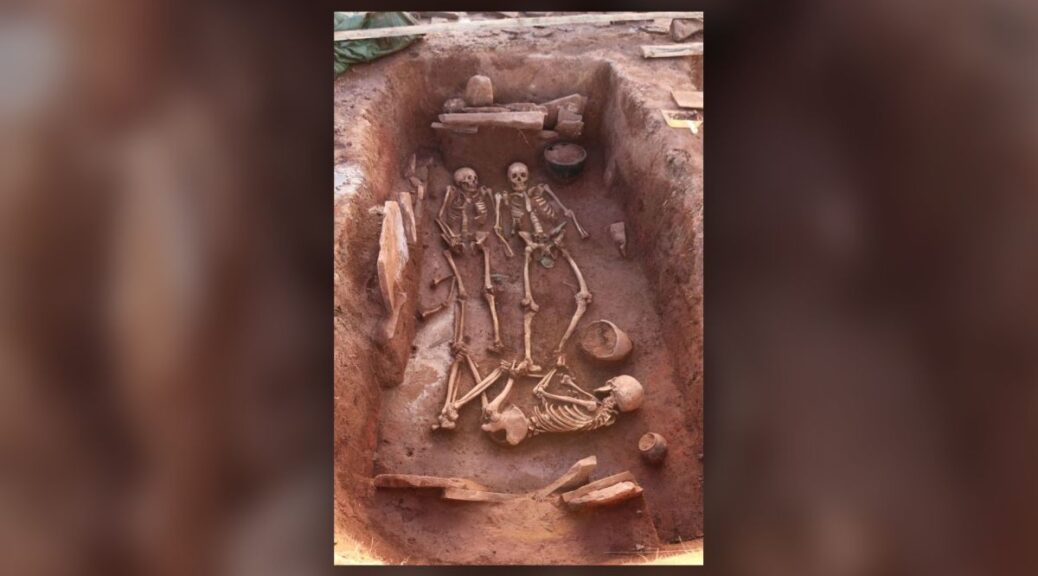

In the barrow four women of different age were buried: two young women of 20-29 years old and 25-35 years old, a teenage girl of 12-13 years old and a woman of 45-50 years old. The burial was made simultaneously as one of the piles supported the floor of the tomb was in the dromos and completely overlaid the entrance so that it would be absolutely impossible to overtake it during next burials.

The burial was robbed in ancient times. The robbers broke into the tomb from the north when the floor had already fallen and the sepulchre was buried i.e. in 100 or 200 years after the barrow was filled. However, only northern and eastern parts of the tomb had been robbed where there were the remains of the teenager and one of the young women.

Apart from the spread remains we found in the northern part of the pit more than 30 iron arrowheads, an iron hook in the shape of a bird, fragments of horse harness, iron hooks for hanging harness, iron knives, fragments of moulded vessels, multiple animals’ bones. In filling the robbers’ passage the broken black lacquer lacythus with red-figure palmette dated back to the second –third quarter of the 4th c BC was found.

At the southern and western wall, there were two untouched skeletons laid on the wooden beds covered by grass beddings. One of them belonged to a young woman buried in a “position of a horseman”. As the researches of the anthropologists have shown to lay her in such way the tendons of her legs had been cut. Under the left shoulder of a “horsewoman”, there was a bronze mirror, on the left, there were two spears and on the left hand, there was a bracelet made of glass beads. In the legs, there were two vessels: a moulded cassolette and a black lacquer one hand cantharos which was made in the second quarter of the 4th c BC.

The second buried was a woman of 45-50 years old. For the Scythian time, it was a respectable age as the life expectancy of a woman was 30-35 years old. She was buried in a ceremonial headdress, calathos, the plates of which were preserved decorated with the floral ornament and the rims with the pendants in the shape of amphorae.

As the researches have shown the jewellery was made from the alloy where approximately 65-70% was gold and the rest is the pollution of copper, silver and a small per cent of iron. This is quite a high percent of the gold for Scythian jewellery which was often made in the workshops of Panticapaeum from electrum, the alloy of gold and silver whereas the gold could be approximate of 30%.

“Found calathos is a unique find. This is the first headdress in the sites of Scythian epoch found on Middle Don and it was found in situ on the location on the skull. Of course, earlier similar headdresses were found in known rich barrows of Scythia. However, only a few were discovered by archaeologists.

They were more often found by the peasants, they were taken by the police, landowners and the finds had been through many hands when they came to the specialists. That is why it is not known how well they have been preserved. Here we can be certain that the find has been well preserved”, noted Valerii Guliaev.

Along with the older woman an iron knife was laid wrapped into a piece of fabrique and an iron arrowhead of quite a rare type, tanged with a forked end. These finds and also many details of the weapon and horse harness allow suggesting that the Amazons, women-warriors whose institution was in the Scythian epoch among Iranian nomadic and semi-nomadic tribes of Eastern Europe, were buried in this barrow. Such horsewomen probably were cattle, belonging and dwelling guardians while the men went to long-term warpaths.

“The Amazons are a common Scythian phenomenon and only on Middle Don during the last decade our expedition has discovered approximately 11 burials of young armed women. Separate barrows were filled for them and all burial rites which were usually made for men were done for them. However, we come across burials with four Amazons of such different age for the first time”, said Valerii Guliaev.

The burial was made in autumn at the end of the warm period. The researches done by paleozoologists of IA RAS helped to figure it out. In the grave pit, the bones of six-eight months old lamb were found which some time ago had been in a bronze cooking pot dag into the ground in the centre of the grave.

The robbers took the pot which was of great value and the bones greened from being rested in a bronze dish for a long time had been thrown away. Since the sheep usually lamb in March-April, it was concluded that the burial which the barrow had been filled for was done not later than November.

The finds in the burial have raised questions for scientists who still do not have any answers.

“We have come across an enigma: we have two women in their prime of life, one is a teenager and another is a woman quite old for the Scythian epoch. It is not clear how they could die at the same moment. They do not have any traces of bones injuries. These women’s bones have been spread. There are some marks of tuberculosis and brucellosis, but these illnesses cannot cause death simultaneously. That is why we still cannot understand what the cause of death was and why four women of different age were buried at the same time”, asks Valerii Guliaev.

Provided by Institute of Archaeology of Russian Academy of Sciences