Scientists Reveal a Perfectly Preserved 18,000-year-old Puppy Discovered Frozen in Russia

An ancient dog finds in Russia in the Far East that he lived a glorious eighteen thousand years ago. It was found last year in a frozen mud near the city of Yakutsk in Siberia and has been given the affectionate name of “Dogor”.

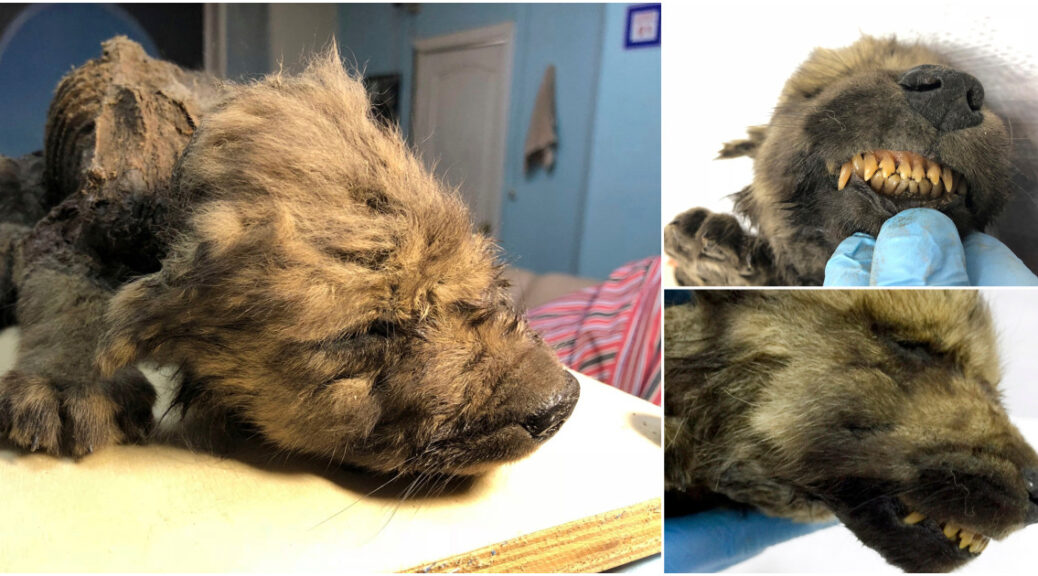

More surprising is that it is unusually good with intact fur, skin, whiskers, and eyelashes. It might look just like a sleeping old dog to the casual viewer!

The Russian Wolfhound, also known as the Borzoi breed, is a special dog of tremendous speed, known for the rather remote appearance, associated with Russia.

A quick online search showed that in Russia other dogs mixed wolves with hundreds of massive beast dogs that have been domesticated by patient owners. The owners insist these dogs are half-wolf; whether they’ve been genetically proven to be so is another matter.

That is what scientists believe they have found buried deep in the ice in the Far East reaches of Siberia; an almost perfectly preserved specimen that even retains its fur.

As yet, experts have not determined whether the animal is dog or wolf, but that riddle, they say, is half the fun of the quest. One thing is for sure, it looks like a puppy and perhaps is an evolutionary cross between wolf and dog.

A piece of the puppy’s bone was immediately shipped off to Stockholm’s Centre for Paleogenetics to determine just what scientists were looking at.

They have determined the animal is 18,000 years old and is preserved perfectly, thanks to the ice in which it was buried.

“We have now generated a nearly complete genome sequence from it and normally when you have two-fold coverage genome, which is what we have, you should be able to relatively easily say whether it’s a dog or a wolf, but we still can’t say, and that makes it even more interesting,” said Love Dalen, professor of evolutionary genetics at the centre.

Whatever the animal’s true ancestry turns out to be, the remains now have a name that applies in either case: Dogor, which is Yakutian for a friend.

Dogor remains are now kept at a private facility, the Northern World Museum. Museum director Nikolai Androsov said, at Dogor’s unveiling to the media, “this puppy has all its limbs…even whiskers.

The nose is visible. There are teeth. We can determine due to some data that it is male” he said at the presentation of Dogor at Yakutsk’s famed Mammoth Museum, which specializes in ancient remains and specimens.

How the prehistoric puppy perished is so far unknown, although scientists do know he was just eight weeks old. Researchers will no doubt continue testing to learn all they can about the fascinating creature.

Russia’s the Far East has provided many incredible finds and animal remains for scientists who study ancient animals in recent years.

Buried deep within Siberia’s permafrost, remains of woolly mammoths, canines and other prehistoric animals are being discovered whenever the ice melts. Mammoth tusk hunters are oftentimes the ones who discover them.

Who knows? One day Dogor the prehistoric puppy may become part of a Russian children’s story, or the basis of a movie. He has already joined other furry, famous canines in getting worldwide attention.