Viking Chess piece bought for less than $10 sells for over $1.3M

A 900-year-old Viking chess piece purchased for $6 in the 1960s recently sold at auction for $1.3 million.

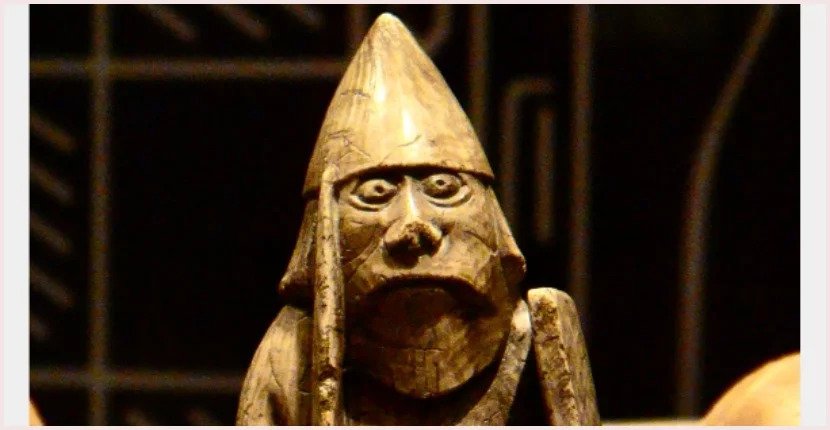

The Lewis Chessmen are intricate chess pieces in the form of Norse warriors that were carved from walrus ivory in the 12th century. A large hoard of the chess pieces, totaling 93 objects making up some four chess sets, was discovered in 1831 on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland.

The elaborately carved pieces soon became featured attractions at museums. Of the 93 pieces, 82 are now in the British Museum in London and 11 are in the collection of the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.

Five of the pieces, however, were missing. In June 2019, Sotheby’s announced it had authenticated a missing piece, the equivalent of a rook, and would sell it in with an estimated value of $1 million.

The missing piece had been bought in 1964 by an antique dealer in Edinburgh and passed down through this family. For some time, the Chessman was kept in a drawer at the home of the antiques dealer’s daughter.

According to The Guardian, a family member said it had been stored away in their grandfather’s house, with everyone unaware of its importance

“When my grandfather died my mother inherited the chess piece,” said a family spokesperson. “My mother was very fond of the chessman as she admired its intricacy and quirkiness.

She believed that it was special and thought perhaps it could even have had some magical significance. For many years it resided in a drawer in her home where it had been carefully wrapped in a small bag. From time to time, she would remove the chess piece from the drawer in order to appreciate its uniqueness.”

Alexander Kader, the Sotheby’s expert who eventually examined the piece for the family, told The Guardian that his jaw dropped when he saw it, and he knew immediately what it was. “I said: ‘Oh my goodness, it’s one of the Lewis chessmen.’ ”

He added: “They brought it in for an assessment. That happens every day. Our doors are open for free valuations. We get called down to the counter and have no idea what we are going to see. More often than not, it’s not worth very much.”

The 3.5-inch warder is a bearded figure with a sword in his right hand and shield at his left side.

Experts believe that this Viking chess piece along with the rest of the Lewis chessmen hail from Trondheim, Norway, which specialized in carved gaming pieces in the 12th and 13th centuries.

The Isle of Lewis was Norwegian territory until 1266, and one theory is that the chess set was buried there after a shipwreck.

Lewis was on a thriving trade route between Norway and Ireland and another theory is that they were hidden for safekeeping by a traveling merchant.

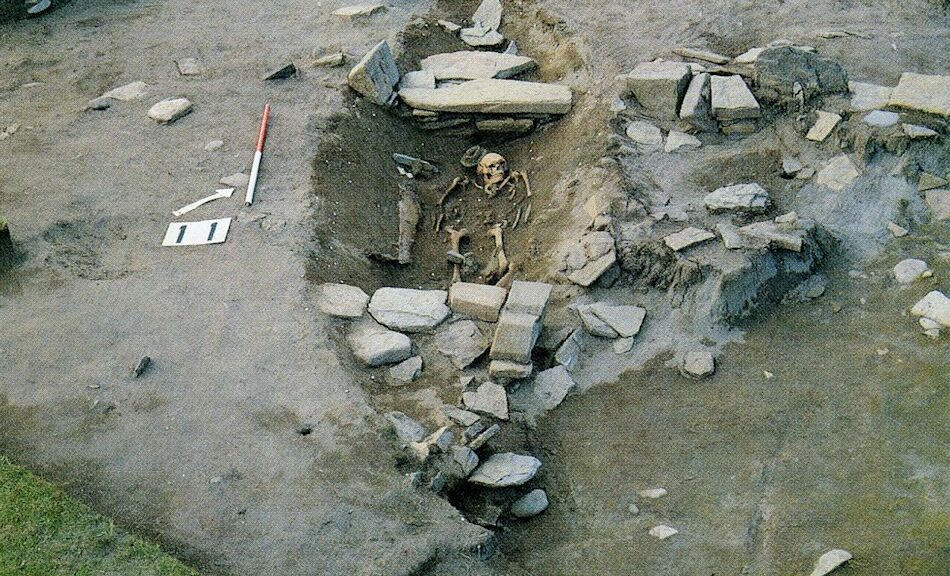

They became arguably Scotland’s best known archaeological find when they were found buried in the beach of Uig Bay in 1831, said The Guardian. :How they were discovered is still disputed, with one account claiming they were uncovered by a grazing cow.”

The Lewis Chessmen are “steeped in folklore, legend and the rich tradition of story-telling,” Sotheby’s said in a press release, adding that they are “an important symbol of European civilization.”

Alexander Kader said in a statement, “It has been such a privilege to bring this piece of history to auction and it has been amazing having him on view at Sotheby’s over the last week—he has been a huge hit. When you hold this characterful warder in your hand or see him in the room, he has real presence.”

Since their discovery in the 19th century, a Viking chess piece and the Lewis chessmen has become an important symbol of European civilization, often inspiring portrayals in pop culture, such as the life-size chess game in the film adaptation of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.