Caral: The Oldest Civilization in the Americas

Caral (also referred to as Caral-Supe) is a stunning ancient city located in the Supe Valley of Peru. Today travellers can visit the Caral Ruins, which are believed to be the remains of one of the oldest cities in the Americas.

Rewind time and the city of Caral was once a thriving metropolis for its local residents around the same time that the Egyptian pyramids were being built! Interestingly, Caral remains relatively unknown on an international level.

The ancient city of Caral

Caral: A brief history

The Caral Ruins have located about 200 km (125 miles) north of Lima in Peru. Paul Kosok, American history and government professor were one of the first to study Caral in 1948. At the time, his findings were largely ignored due to the fact that he didn’t find any typical and sought after Andean artefacts on site. Peruvian anthropologist and archaeologist, Ruth Shady, later took over the exploration of this desert city of pyramids.

The evidence collected suggests that Caral was inhabited some 5,000 years ago, between 2600 and 2000 BCE (Before the Common Era, or Before Christ). For comparative purposes, the Great Pyramid of Khufu in Egypt was built around 2600 BCE.

Excavators described Caral as the oldest American urban centre, but this claim to fame was later challenged when older ancient sites were found close by. Caral is however the largest known ancient city in the Andean region. Researchers believe that the city may have been an urban design model that was later adopted by various Andean civilizations over the course of the next millennia. In this respect, the discovery of Caral answers questions about the development of other early cities built after Caral and the origins of civilization in the Andes.

The size of Caral – think BIG

Caral is approximately 60 hectares in size and was home to 3,000 inhabitants. This makes Caral one of the biggest Norte Chico sites: the Norte Chico civilization was a complex pre-Colombian society encompassing over 30 population centres in what is now known as the Norte Chico region of the north-central Peruvian coast.

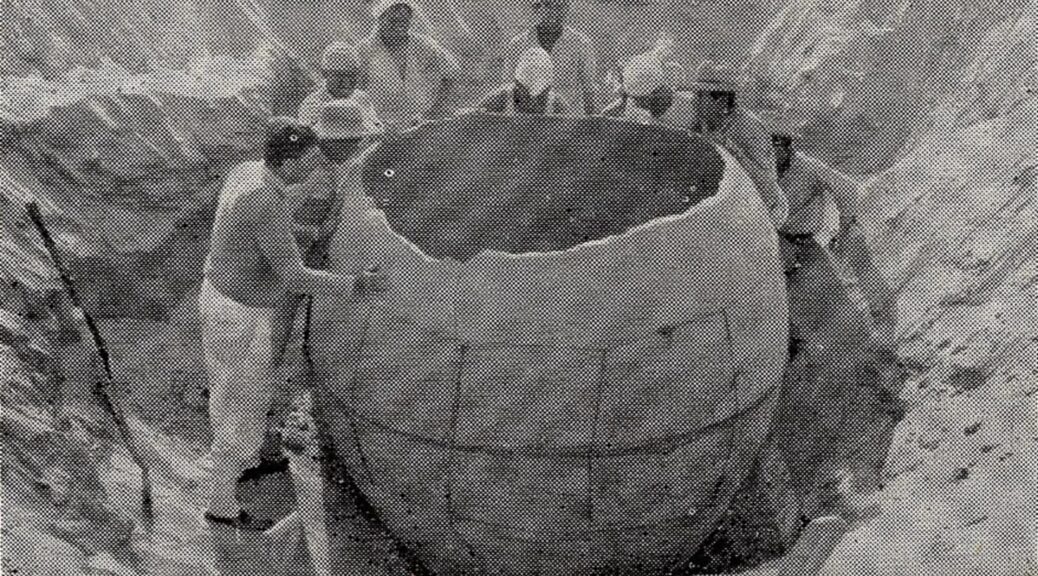

Caral is only one of a total of 19 settlements found in the Supe Valley. The remains of the Caral urban complex spreads out more than 150 acres (607,000 ms) and include residential buildings, temples and plazas. The most stunning findings at Caral include the Main Pyramid, the Amphitheater Pyramid, and the residential Quarters of the Elite. The main pyramid at Caral is 60 ft (18 m) tall and almost as large as 4 football fields! Ruth Shady believes that Caral was the main focus of the civilization living in the Supe Valley.

What sets Caral apart?

What sets Caral apart is not just its size, but also its age. Carbon dating of various organic materials found throughout the site indicates that the pyramids are approximately 5,000 years old!

Interestingly, the people that lived in Caral were dedicated to buildings with civic intensity, and dedication to construction improvements and additions, and the city saw periods of great change. They were always making and remaking the stone-and-mortar walls, plazas, and residences; building new floors; painting and repainting surfaces; breaking down walls, and making new ones. They were truly one of the first civilizations that we’re focused on making home improvements.

The artefacts: Love, not war

No weapons, battlements or mutilated bodies were found during the Caral excavations. This crucial evidence lead anthropologist Ruth Shady’s research to suggest that this was a peaceful society based on commerce and pleasure.

When excavating one of the pyramids, flutes made from pelican and condor bones were found along with cornetts made from llama and deer bones. The stunning remains of a child found wrapped and buried with a stone bead necklace were also discovered.

Another artefact found at Caral was a quipu. The quipu is a record-keeping system in which knots are tied on a rope. According to Gary Urton, a quipu was used in a binary manner, to record both phonological and logographic data. The Incas later used and perfected this system, providing further proof that the Caral civilization culture impacted the Inca Empire.

The fabled missing link

For many decades, archaeologists have searched for a missing link in archaeology or a “mother city”- a city that could answer questions about why and how humans became civilized. Researchers have long looked for the answer to this question in other parts of the world, such as in Egypt, China, India, and Mesopotamia (Iran). No one expected that the first signs of city life could be found in a Peruvian desert.

For many years historians believed that the fear of war was perhaps a primary motivator for people to build cities and form complex societies to protect themselves against threats. Caral however has no traces of warfare or weapons, yet the city became a thriving metropolis. This finding challenges modern ideas of the origins of cities as based on conflict.

Ruth Shady explained that Caral was home to a gentle society: “This great civilization was based on trade in cotton. Caral made the cotton for the nets, which were sold to the fishermen living near the coast. Caral became a booming trading centre and the trade spread.”

Caral was built on the basis of trade, not bloodshed. Warfare actually emerged way later in history. And this is what the finding of Caral as a “mother city” indicates: civilizations are not born in conflict – they are born in peace. It is time to re-think the emergence of civilization!

After almost 10 years of excavation, the great proportions of this grand site are now emerging in Caral, but much work remains to be done. When standing in the main plaza with pyramids surrounding you on every side, the power of a long-lost ancient city is felt. Discoveries made in the area continue to help answer the question: how and why did humans become civilized?