Analysis Links the Origins of the Maya and Corn Cultivation

In Maya creation myths, the gods created humans out of corn. Now, a new study from a site in Belize suggests corn really was important in the origin of the ancient Maya: More than half of their ancestry can be traced to migrants who arrived from South America sometime before 5600 years ago, likely bringing with them new cultivars of the crop that sustained one of Mesoamerica’s great cultures.

These previously unknown migrants “were the first pioneers who essentially planted the seeds of Maya civilization,” which emerged about 4000 years ago, says archaeologist and co-author Jaime Awe.

A native Belizean now at Northern Arizona University, he, like many people in Belize, has some Maya ancestry. “Without corn, there would have been no Mayans.”

The discovery reveals a significant new source of ancestry for the Maya, whose civilization spanned one-third of Central America and Mexico, dotting the region with cities and monuments at its height more than 1000 years ago.

Today, the Maya are an ethnolinguistic group of at least 7 million Indigenous peoples in Central America.

The study also suggests that as in Europe, where farming arrived with immigrants from the Middle East, farming in the Americas spread as least in part with people on the move, rather than simply as know-how passed between cultures.

“This paper is really groundbreaking,” says Mary Pohl, a Maya archaeologist at Florida State University. “This is a dramatic revelation and is really stirring things up.”

Awe, a Maya archaeologist and former director of the Belize Institute of Archaeology, had long wondered how the Maya were related to the hunter-gatherers and early farmers who brought maize, manioc, and chiles to what is now Mexico, Belize, and Guatemala. But poor preservation of bones and DNA in the hot and humid climate had left few clues.

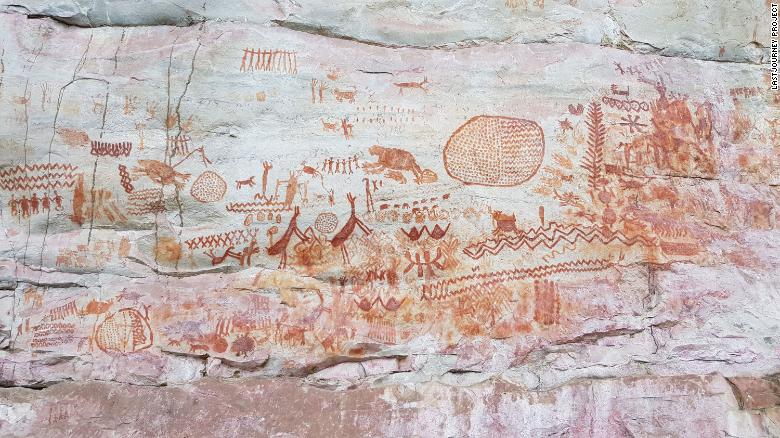

The new study analyzes remain from two rock shelters on the steep slopes of old-growth rainforest in the Bladen Nature Reserve in southwestern Belize, a 2.5-kilometre hike from the nearest road.

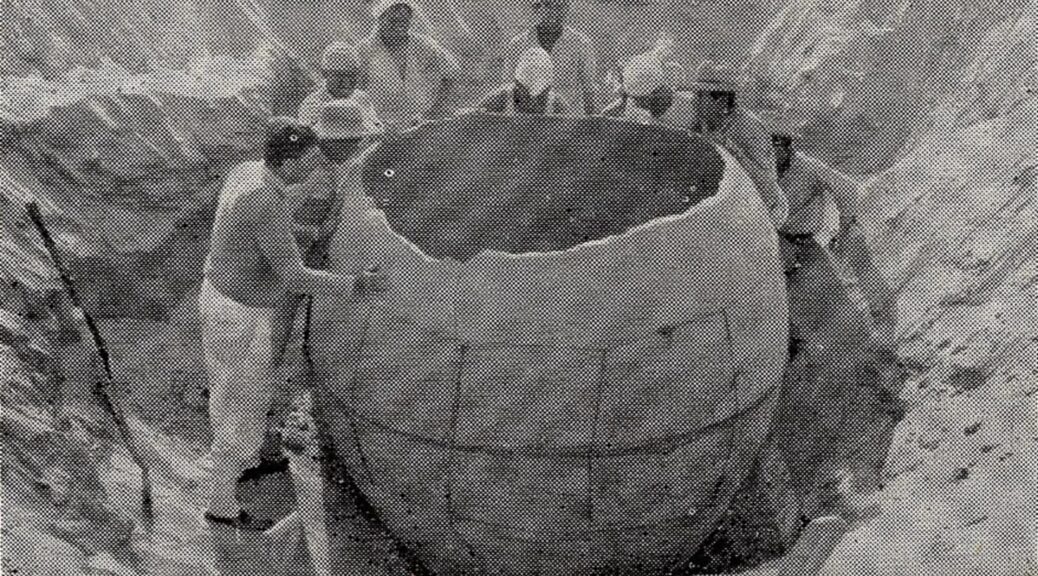

Since 2014, archaeologist Keith Prufer of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, wildlife biologist Said Gutierrez of the Ya’axché Conservation Trust, and their colleagues have unearthed more than 85 skeletons from shallow graves in the rock shelters’ dry dirt floors.

The archaeologists directly dated 50 individuals with radiocarbon, finding they lived between 1000 to 9600 years ago. Then, population geneticist David Reich of Harvard University and his team managed to extract high-quality ancient DNA from the inner ear bones of 20 individuals—“the oldest human DNA from a tropical rainforest site,” Reich says.

They analyzed 1.2 million nucleotide bases across the genomes and compared them to DNA from ancient and living people from the Americas.

The comparisons showed the earliest people buried at the rock shelters, 9600 to 7300 years ago, closely resembled that of hunter-gatherers descended from an ancient migration from North to South America. But after 5600 years ago, the DNA recorded a major shift: All 15 individuals tested were most closely related to another group of Indigenous people who today live from northern Colombia to Costa Rica and who speak Chibchan languages. “It’s clearly a major movement into the Maya region of people related to Chibchan speakers,” Reich says.

The migration had a lasting impact: Reich’s team found that living Maya has inherited more than half of their DNA from this influx from the south, they reported today in Nature Communications. Half of the remainder came from the ancient hunter-gatherers who were first in the region, the rest from ancestors of people in the Mexican highlands.

The population shift eventually led to a new diet. Prufer and archaeologist Douglas Kennett at the University of California, Santa Barbara, had previously analyzed carbon isotopes from the teeth of the people in the rock shelters, which shows the kind of food they ate. As reported in Science in 2020, they found a steady increase in maize consumption over time. The ancient hunter-gatherers got less than 10% of their diet on average from maize. The first migrants from the south also ate relatively little corn. But then, between about 5600 years ago and 4000 years ago the proportion of maize surged, from 10% to 50%, providing “the earliest evidence of maize as a staple grain,” Prufer says.

The shift to maize happened hundreds of years after the influx of migrants, but the team says its results fit with the emerging story of maize cultivation. The plant was partially domesticated as early as 9000 years ago in southwest Mexico, but over the past 8 years, genetic and archaeological evidence has shown that it wasn’t fully domesticated until 6500 years ago—at sites in Peru and Bolivia. There, farmers developed larger, more nutritious cobs than the partially domesticated maize still found in Mexico 5300 years ago, says archaeologist Logan Kistler of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History (NMNH).

Together, the evidence suggests the migrants brought improved maize plants from the south by 5600 years ago, perhaps with methods for growing corn in small gardens, says Kennett, a co-author. By 4000 years ago it had become the keystone crop. That scenario could explain why one early Maya language incorporates a Chibchan word for maize, says linguist and co-author David Mora-Marín of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

In tracing the origin of one of Mesoamerica’s great peoples, the genetic and isotopic work also illuminates the evolutionary roots of one of the world’s most successful crops, says archaeobotanist Dolores Piperno of NMNH and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. “It really transforms our knowledge of how maize dispersed.”