Archaeologists identify oldest Muslim graves ever found in Europe

An archaeological site in northeast Spain holds one of the oldest-known Muslim cemeteries in the country, with the discovery of 433 graves, some dating back to the first 100 years of the Islamic conquest of the Iberian Peninsula.

The finds confirm that the region, along the frontier between the warring Islamic and Christian worlds in the turbulent early Middle Ages, was once dominated by Muslim rulers, who were later replaced by Christian rulers and their history forgotten.

The archaeologists unearthed the ancient graves from a maqbara or Muslim necropolis, dating from between the eighth and the 12th centuries, this summer in the town of Tauste, in the Ebro Valley about 25 miles (40 kilometres) northwest of Zaragoza.

The remains show that the dead were buried according to Muslim funeral rituals and suggest the town was largely Islamic for hundreds of years, despite there being no mention of this phase in local histories.

“The number of people buried in the necropolis and the time it was occupied indicates that Tauste was an important town in the Ebro Valley in Islamic times,” lead archaeologist Eva Giménez of the heritage company Paleoymás told Live Science.

Giménez and the company Paleoymás were contracted for the latest excavations by El Patiaz Cultural Association, which was founded by local people in 1999 to investigate the history of the town.

Their initial excavations in 2010 suggested that a 5-acre (2 hectares) Islamic necropolis at Tauste might hold the remains of up to 4,500 people. But the association’s limited funds meant only 46 graves could be unearthed in the first four years of work.

Giménez said the latest discoveries hint that even more Muslim graves could still be found. “We now have information that indicates that the size of the necropolis is greater than what was known,” she said.

Muslim conquest

The graves date all the way back to the time when Muslim armies from North Africa that were allied with Islam’s Umayyad caliphate in Damascus invaded what is now Spain in A.D. 711. By 718, they had conquered most of the Iberian Peninsula — today’s Spain and Portugal — except for some mountainous regions of the northwest that remained independent Christian kingdoms.

The Muslim invaders, called “Moors” by the Christians, then attempted to conquer Gaul — now France — but were turned back, first at the Battle of Toulouse in 721 and then at the Battle of Tours in 732, where they were defeated by a smaller Frankish army led by the nobleman Charles Martel. It’s said the Frankish use of heavy cavalry played a decisive part in the battle, Live Science previously reported.

After that, Muslim leaders established their rule south of Barcelona and the Pyrenees, the mountain range that divides Spain and France. The Ebro Valley around Zaragoza, however, stayed in Muslim hands.

The Muslim-ruled region became known as al-Andalus — with the “Andal” part possibly from the name of the Vandals the Muslims had conquered — and reached its cultural peak in about the 10th century with advances in mathematics, astronomy and medicine. By some accounts, the regime was relatively benign. Jews and Christians were allowed to practice their religions if they chose not to convert to Islam, but they paid extra tax, called jizya, and were treated as a lower social class than Muslims.

Muslim rule in Spain began to fragment after the 11th century, and the Christian kingdoms in the north grew more powerful. The last Muslim emirate, at Granada, was defeated in 1492 by the armies of Castile in the final battle of the Christian Reconquista led by Isabela and Ferdinand, the first queen and king of Spain. Islam was outlawed, and violent anti-Muslim persecutions continued until the early 17th century.

The influence of Islamic rule has been recognized in nearby parts of the region, but history was silent about the Islamic phase at Tauste.

Ancient graves were sometimes unearthed in the town, but they were dismissed as those of victims of a cholera pandemic that killed almost a quarter-million people in Spain in 1854 and 1855, said Miriam Pina Pardos, the director of the Anthropological Observatory of the Islamic Necropolis of Tauste for El Patiaz.

Unearthing Islam

Some members of El Patiaz suspected an 11th-century church tower in the town had Islamic origins — a suspicion confirmed when examinations showed it was once a minaret in the distinctive Zagri architecture..

So in 2010, the group began excavations led by archaeologist Francisco Javier Gutierrez. They learned the ancient graves at Tauste contained individuals buried with Muslim rituals, and not in the style of a mass burial that might have been expected for victims of the cholera pandemic, Pina Pardos said.

For instance, each grave held the remains of a single person, typically placed lying on their right side so that their gaze was oriented toward Mecca, and each was covered with a mound of earth, Gutierrez said. Some may also have had a wooden cover, now missing.

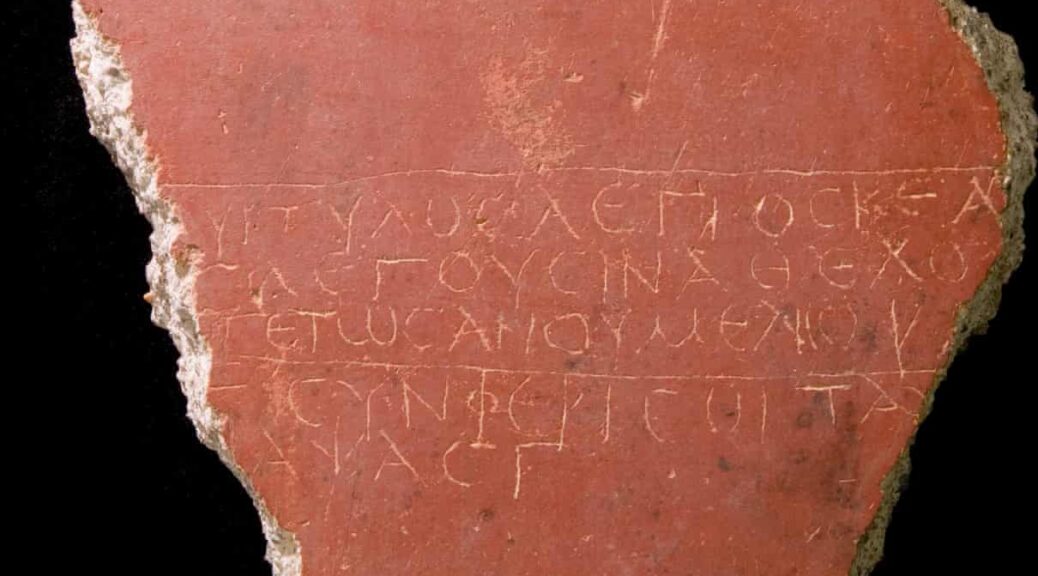

The graves also showed other distinctive Muslim features: They were just large enough to accommodate the body, and the dead were buried in a white shroud, regardless of their social status, she said. To this day, Muslim rituals do not allow the dead to be buried with grave goods, but fragments of ceramics found nearby in the excavations since 2010 showed they dated to between the eighth and 12th centuries, Giménez said.

While the existence of the Islamic graveyard was known from the earlier excavations, “what was not known where the dimensions and density of the tombs,” she said. “It has been expected and unexpected at the same time.”

The latest discoveries, in a single street known to be part of the ancient necropolis, show the extent of Muslim influence in the town over several centuries.,

The cemetery was in use continuously for more than 400 years, they found. “This tells us about a constant and deeply rooted [Islamic] population in Tauste since the beginning of the eighth century,” Giménez said.