3,000 Years old Buhen: The Sunken fortress under the Nile

During the Middle Kingdom era, King Senusret III established castles and fortresses to protect Egypt from the south, such as the Buhen fortress that sunk in the Nile as a result of a flood.

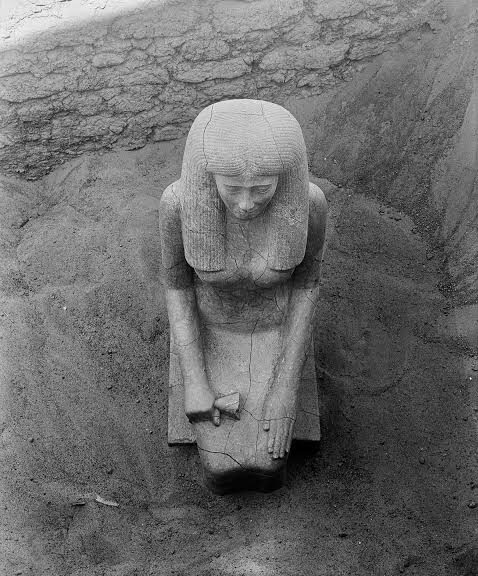

Buhen was a massive fortress located on the west bank of the Nile in Lower Nubia (northern Sudan). The walls of the fortress were made of brick and stone walls, approximately 5 meters (16 ft) thick and about 10 meters (33 ft) high, covering an area of about 13,000 square meters (140,000 sq ft) and extending more than 150 meters (490 ft).

It was constructed during the reigns of King Senusret III in the Middle Kingdom era (12th dynasty) to protect Egypt and the commercial ships from rebel Nubians in the south, according to “Ancient Egypt” by David P. Silverman.

The massive fortress was built in 1860 BC. It had about 1,000 soldiers, 300 archers, and their families. Queen Hatshepsut ordered a Horus temple to be built inside the Buhen fortress for worship and prayer, and also for traders to take a break while transporting their goods. Interestingly, during that time, Egypt imported and exported many products, such as oils, ivory, pottery, and tiger, and elephant skins.

The Middle Kingdom era saw many other fortresses besides Buhen, such as Mirgissa, Shalfak, Uronarti, Askut, Dabenarti, and ending with the paired fortresses of Semna and Kumma, located on opposite sides of the Nile River. Each fortress was in visual contact with the immediately adjacent forts.

Ahmed Saleh, director of antiquities in Aswan, told Egypt online portal that the Buhen fortress no longer exists because it was submerged under the waters of Lake Nasser in 1964 due to the flood; the Buhen fortress is now located 300 meters from the High Dam. He added that the Ministry of Antiquities did not search for it because it was certainly destroyed, like several other Egyptian antiquities. Among the most important ancient monuments lost under Lake Nasser are Nubian fortresses.

“But if the Ministry planned to look for antiquities under the waters of Lake Nasser, they could find nothing other than bones, noting that the level of water was higher than the level of the ground.

Therefore, the Egyptian government built the High Dam, but it, unfortunately, swept away several pharaonic artifacts; still, the Ministry of Antiquities saved many artifacts, in cooperation with more than 22 foreign research teams, such as the UNESCO Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia, which began in the 1960s.

The site was entirely submerged beneath the reservoir waters and rendered inaccessible. However, the campaign saved many temples, including the Hatshepsut and Philae temples, which were rescued and moved to places nearby,” Saleh added.

History of Egypt in the Middle Kingdom

The Middle Kingdom era is called the era of economic prosperity because of many economic projects, such as irrigation, trade, industry, and agriculture. Among the most famous kings of the Middle Kingdom were King Mentuhotep II, who restored the unity of the country and spread security after the chaos that plagued Egypt in the era of the Old Kingdom, and King Senusret III, who was one of the greatest kings of Egypt.

Senusret III took care of the army to protect Egypt and led many campaigns to secure its borders. He also ordered the digging of the Sesostris Canal to link the Red Sea and the Nile, as well as building a dam to protect the land in Fayoum from the flood.

The Sesostris Canal was the source of the idea to build the Suez Canal to connect the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea, which became the most important navigational channel in the world and an important source of income for Egypt.

King Amenemhat III ruled from c. 1860 BCE to c. 1814 BCE. He was interested in agriculture and irrigation, and he ordered the building of the first pyramid at Dahshur, the so-called “Black Pyramid”, near Fayoum.

Around the 15th year of his reign, the king decided to build a new pyramid at Hawara, as well as a huge temple called “Labyrinth,” named so due to a large number of rooms, roads, and corners inside it, making it difficult for any visitor to exit.

Unfortunately, as a result of the kings’ weaknesses and greed, chaos spread in the country, which allowed the Hyksos, who came from Asia, to occupy Northern Egypt. The Hyksos abused the Egyptians very much and destroyed many temples and several ancient antiquities.

The Egyptians were determined to fight and expel the Hyksos from their country. The struggle started from Upper Egypt, led by Seqenenre Tao, who was martyred in the war with the Hyksos, but his wife Ahhotep encouraged the Egyptians to continue the struggle.

She urged her eldest son, Kamose, to continue the struggle, but he was also martyred in one of the battles. Then, the army was taken over by the younger son of Seqenenre Tao, Ahmose I, who continued to fight the Hyksos until they were expelled from Egypt. He then ruled the country.

One of the greatest civilizations throughout history is the ancient Egyptian civilization, which has stunned the entire world for ages. During the Middle Kingdom era, when Egypt was at the highest degree of culture and development, and kings were interested in projects of benefit to the people, handicrafts were developed and literature and art flourished.