Iron Age Rock Art Discovered During Rescue Excavation Beneath House in Turkey

An unexpected discovery has revealed ancient artwork that was once part of an Iron Age complex beneath a house in southeastern Turkey. The unfinished work shows a procession of deities that depicts how different cultures came together.

Looters initially broke into the subterranean complex in 2017 by creating an opening on the ground floor of a two-story home in the village of Başbük. The chamber, carved into the limestone bedrock, stretches for 98 feet (30 meters) beneath the house.

When the looters were caught by authorities, a team of archaeologists did an abbreviated rescue excavation to study the significance of the underground complex and the art on the rock panel in the fall of 2018 before erosion could further damage the site. What the researchers found has been shared in a study published Tuesday by the journal Antiquity.

The artwork was created in the 9th century BC during the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which began in Mesopotamia and expanded to become the largest superpower at the time.

This expansion included Anatolia, a large peninsula in Western Asia that includes much of modern-day Turkey, between 600 and 900 BC.

“When the Assyrian Empire exercised political power in south-eastern Anatolia, Assyrian governors expressed their power through art in Assyrian courtly style,” said study author Selim Ferruh Adali, associate professor of history at the Social Sciences University of Ankara in Turkey, in a statement.

An example of this style was carved monumental rock reliefs, but Neo-Assyrian examples have been rare, the study authors wrote.

Combining cultures

The artwork reflects an integration of cultures instead of outright conquest. The deities have their names written in the local Aramaic language. The imagery depicts religious themes from Syria and Anatolia and were created in the Assyrian style.

“It shows how in the early phase of Neo-Assyrian control of the region there was a local cohabitation and symbiosis of the Assyrians and the Arameans in a region,” Adali said. “The Başbük panel gives scholars studying the nature of empires a striking example of how regional traditions can remain vocal and vital in the exercise of imperial power expressed through monumental art.”

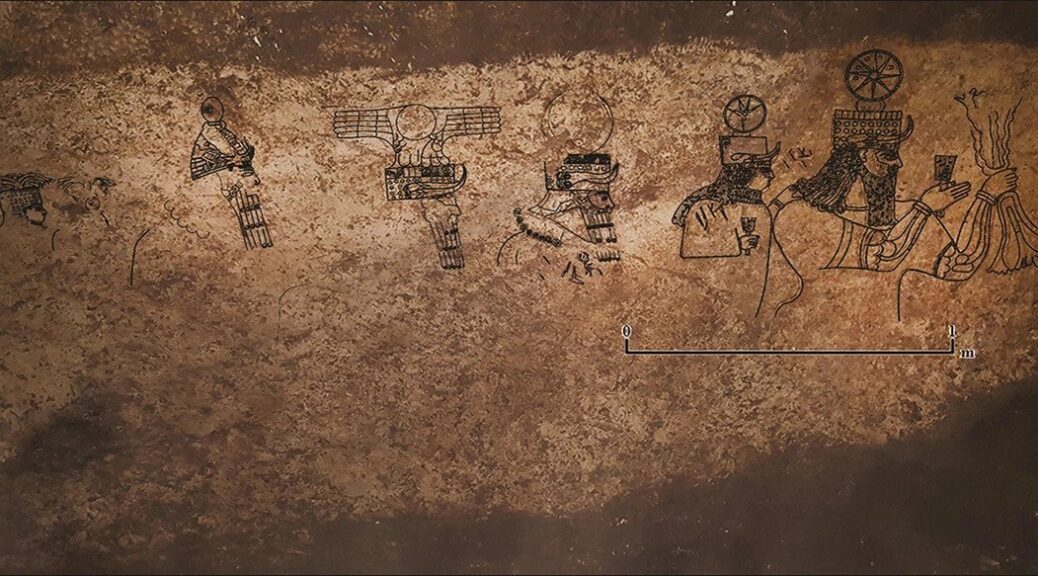

The artwork shows eight deities, all unfinished. The largest is 3.6 feet (1.1 meters) in height. The local deities in the artwork include the moon god Sîn, the storm god Hadad and the goddess Atargatis. Behind them, the researchers could identify a sun god and other divinities.

The depictions combine symbols of Syro-Anatolian religious significance with elements of Assyrian representation, Adali said.

“The inclusion of Syro-Anatolian religious themes (illustrates) an adaptation of Neo-Assyrian elements in ways that one did not expect from earlier finds,” Adali said. “They reflect an earlier phase of Assyrian presence in the region when local elements were more emphasized.”

Upon discovering this artwork, study author Mehmet Önal, a professor of archaeology at Harran University in Turkey, said, “As the dim light of the lamp revealed the deities, I trembled with awe as I realized I was confronted with the very expressive eyes and majestic face of the storm god Hadad.”

Mysteries remain

The team also identified an inscription that may show the name of Mukīn-abūa, a Neo-Assyrian official who served during the reign of Adad-nirari III between 783 and 811 BC.

The archaeologists suspect that he had been assigned to this region at the time and was using the complex as a way to win over the appeal of the local population.

But the structure is incomplete and has remained unfinished for all this time, suggesting that something caused the builders and artists to abandon it — perhaps even a revolt.

“The panel was made by local artists serving Assyrian authorities who adapted Neo-Assyrian art in a provincial context,” Adali said. “It was used to carry out rituals overseen by provincial authorities. It may have been abandoned due to a change in provincial authorities and practices or due to an arising political-military conflict.”

Adali was the epigraphist of the team who read and translated the Aramaic inscriptions in 2019 using photos captured by the research team, who had to work quickly to study the site.

“I was shocked to see Aramaic inscriptions on such artwork, and a sense of great excitement overtook me as I read the names of the deities,” Adali said.

The site was closed after the 2018 excavations because it is unstable and could collapse. It is now under the legal protection of Turkey’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism. The archaeologists are eager to continue their work when excavations can safely resume and capture new images of the artwork and inscriptions and possibly uncover more artwork and artefacts.