An underground city unearthed in Turkey may have been a refuge for early Christians

Archaeologists in southeastern Turkey have unearthed a vast underground city that was built almost 2,000 years ago and could have been home to up to 70,000 people. The subterranean complex may have been a protected space that early Christians used to escape Roman persecution.

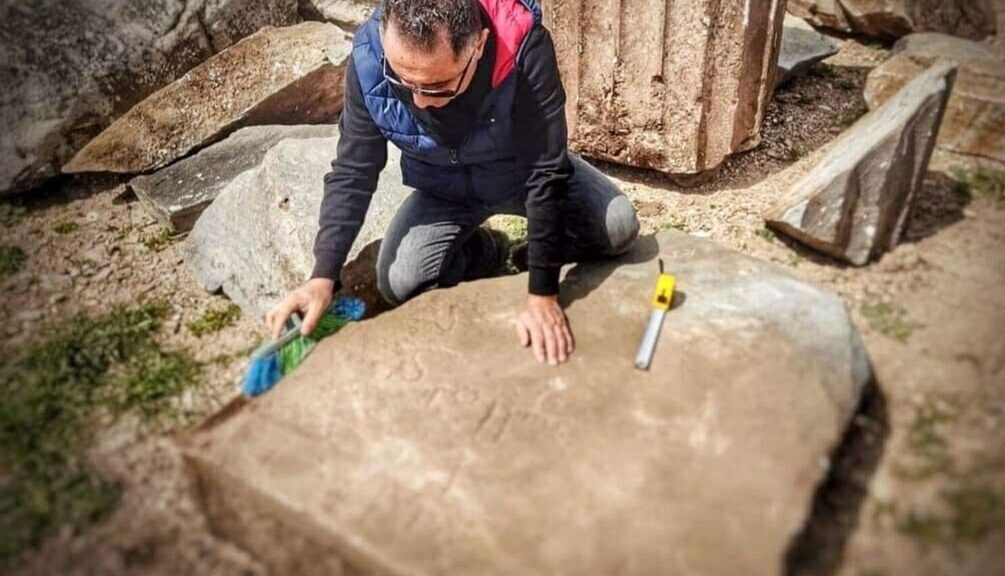

The first underground chambers of the ancient complex were found about two years ago, during a project to clean and conserve historical streets and houses in the Midyat district of Mardin province.

Workers on the project first discovered a limestone cave, and then a passage into the rest of the hidden city, Gani Tarkan, the director of the Mardin Museum and the head of the excavations, told the Turkish government-owned Anadolu Agency. That said, some of the local people had already known that there were caves below Midyat, but had not known there was an entirely underground city, Tarkan told Live Science in an email.

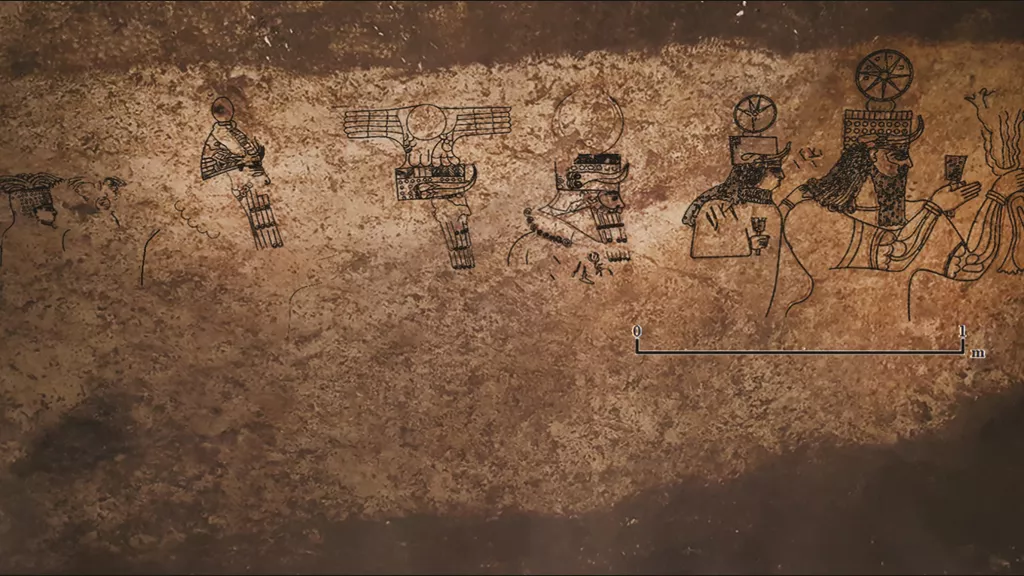

Now, 49 chambers have been unearthed in the colossal complex, as well as connecting passages, water wells, grain storage silos, the rooms of homes, and places of worship, including a Christian church and a large hall with a Star of David symbol on the wall, which appears to be a Jewish synagogue.

Artefacts found in the caverns — including Roman-era coins and oil lamps — indicate that the subterranean complex was built sometime in the second or third centuries A.D, Tarkan told Live Science.

And there is still a large area to excavate. Tarkan estimates that less than 5% of the underground city, now known as Matiate, has been explored so far — an area of over 100,000 square feet (10,000 square m). He thinks the entire complex may be larger than 4 million square feet (400,000 square m) in the area and would have been large enough to accommodate between 60,000 and 70,000 people.

It’s possible that the city originally served as a refuge: “It was first built as a hiding place or escape area,” he suggested.

“Christianity was not an official religion in the second century [and] families and groups who accepted Christianity generally took shelter in underground cities to escape the persecution of Rome,” Tarkan said. “Possibly, the underground city of Midyat was one of the living spaces built for this purpose.”

Ancient geographers wrote that the southern region of what is now Turkey was inhabited by Christians before its more central parts and that Christians in the area were heavily persecuted, not only by the Romans but also by the Persians in the fourth century, he told Live Science.

Medieval travellers in the region at times of war also reported that they’d found entire towns and cities completely empty of inhabitants, and so it was possible the inhabitants had in fact hidden underground in places like Matiate, he said.

In the early first century A.D., Roman officials did not distinguish between Jews and Christians, because many early Christians were also Jews. But that changed in A.D. 64 when Emperor Nero blamed and then killed Christians for a fire that swept through Rome, according to Britannica. Although the persecutions were sporadic, they continued until the early fourth century; and while the numbers are debated, it’s likely that thousands of Christians were executed during this time. In A.D. 313, however, Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, making Christianity legal and ending the persecutions; and in 380 Emperor Theodosius issued the Edict of Thessalonica, making it the official religion of the Roman Empire.

Lozan Bayar, an archaeologist with Mardin’s Office for Protection and Supervision, agreed that Matiate might have been used by early Christians to escape Roman persecution.

“In the early period of Christianity, Rome was under the influence of pagans before later recognizing Christianity as an official religion,” he told Hürriyet Daily News, a Turkish news outlet. Such underground cities provided security to people and they also performed their prayers there. They were also places of escape.”

Hidden city

The ancient city of Midyat above the subterranean complex was likely first built by the Hurrians, a people who occupied parts of central and southern Anatolia (in present-day Turkey) up to 4,000 years ago, during the Bronze Age. The city first appears in Assyrian records in the ninth century B.C. as “Matiate” — a name that meant “city of caves,” possibly because there are many limestone caves nearby — the name that has now been assigned to the underground city.

Midyat was occupied, in turn, by Arameans, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines and Ottomans during its long history, with each civilization building on the work of the last. As a result, Midyat is now well-known for its ancient architecture, and it draws up to 3 million tourists every year, according to Hürriyet Daily News. More than 100 traditional houses near the city’s centre are now protected because of their historical significance, and nine churches and monasteries in the city are listed as UNESCO World Heritage sites.

Tarkan thinks the hidden city of Matiate will be an additional attraction when the excavations are completed.” While the houses on the top are dated to the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, there is a completely different city underneath,” he said. “That city is 1,900 years old.”

Going underground

The tradition of building homes and cities underground is well established in Turkey. More than 40 ancient subterranean cities have been found there, including Derinkuyu — an enormous complex in the central Cappadocia region that was burrowed into soft volcanic rock, possibly by the Anatolian people known as the Phrygians in the eighth and ninth centuries B.C.

Derinkuyu was large enough to hold 20,000 people, and was occupied until the medieval period: for example, Byzantine Christians and Jews used it as a refuge during Arab invasions between the eighth and 12th centuries A.D. Science writer Will Hunt, author of the book “Underground: A Human History of the World’s Beneath Our Feet” (Random House, 2019) said there were many stories of people in what is now Turkey who had found holes in their land, or sometimes right inside their homes, that opened up to sprawling warrens of human-made tunnels.

“Some go down more than 10 levels and have space for tens of thousands of people,” he told Live Science in an email. “They are like upside-down castles.”

Hunt echoes Tarkan’s suggestion that the underground structures at Matiate may have been used in defence. “Beneath any settlement, there would have been an underground city, where people would take cover when they were under attack,” he said.

And it wasn’t just in Turkey: “all over the world, throughout history, whenever there is a threat on the surface, people have dark underground [spaces] to protect themselves from danger,” he said. “It’s practically instinctual.”