Long-Lost Kingdom Over 3,000 Years Old Stumbled on by Archeologists in Turkey

It was said that all he touched turned to gold. But destiny eventually caught up with the legendary King Midas, and a long-lost chronicle of his ancient downfall appears to have literally surfaced in Turkey.

In 2019, archaeologists were investigating an ancient mound site in central Turkey called Türkmen-Karahöyük. The greater region, the Konya Plain, abounds with lost metropolises, but even so, researchers couldn’t have been prepared for what they were about to find.

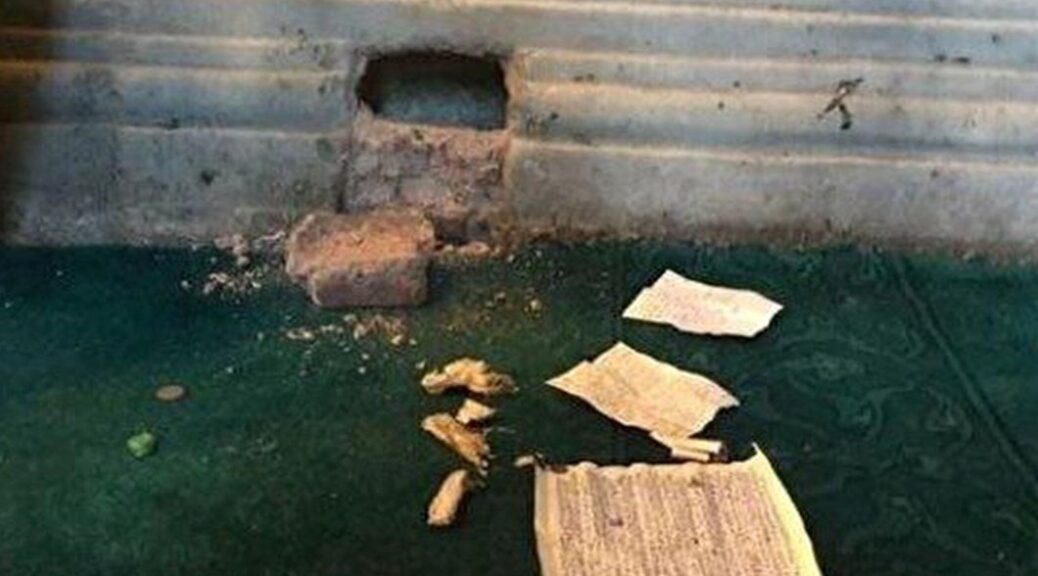

A local farmer told the group that a nearby canal, recently dredged, revealed the existence of a large strange stone, marked with some kind of unknown inscription.

“We could see it still sticking out of the water, so we jumped right down into the canal – up to our waists wading around,” said archaeologist James Osborne from the University of Chicago in early 2020.

“Right away it was clear it was ancient, and we recognised the script it was written in: Luwian, the language used in the Bronze and Iron Ages in the area.”

With the aid of translators, the researchers found that the hieroglyphs on this ancient stone block – called a stele – boasted of a military victory. And not just any military victory, but the defeat of Phrygia, a kingdom of Anatolia that existed roughly 3,000 years ago.

The royal house of Phrygia was ruled by a few different men called Midas, but the dating of the stele, based on linguistic analysis, suggests the block’s hieroglyphics could be referring to the King Midas – he of the famous ‘golden touch’ myth.

The stone markings also contained a special hieroglyphic symbolising that the victory message came from another king, a man called Hartapu. The hieroglyphs suggest Midas was captured by Hartapu’s forces.

“The storm gods delivered the [opposing] kings to his majesty,” the stone reads.

What’s significant about this is that almost nothing is known about King Hartapu, nor about the kingdom he ruled. Nonetheless, the stele suggests the giant mound of Türkmen-Karahöyük may have been Hartapu’s capital city, spanning some 300 acres in its heyday, the heart of the ancient conquest of Midas and Phrygia.

“We had no idea about this kingdom,” Osborne said. “In a flash, we had profound new information on the Iron Age Middle East.”

There’s a lot more digging to be done in this ongoing archaeological project, and the findings so far should be considered preliminary for now. The international team is eager to revisit the site this year, to find out whatever more we can about this kingdom seemingly lost in history.

“Inside this mound are going to be palaces, monuments, houses,” Osborne said. “This stele was a marvellous, incredibly lucky find – but it’s just the beginning.”

You can find out more about the research here and here.