First evidence of unknown ancient ‘Israeli Silk Road’ uncovered in Arava trash dump

Newly uncovered remains of fabrics from the Far East dating to some 1,300 years ago in Israel’s Arava region suggest the existence of a previously unknown “Israeli Silk Road,” according to a team of researchers from Israel and Germany.

“Our findings seem to provide the first evidence that there was also an ‘Israeli Silk Road’ used by merchants along the international trading routes,” said Prof. Guy Bar-Oz from the University of Haifa, who is leading the excavation.

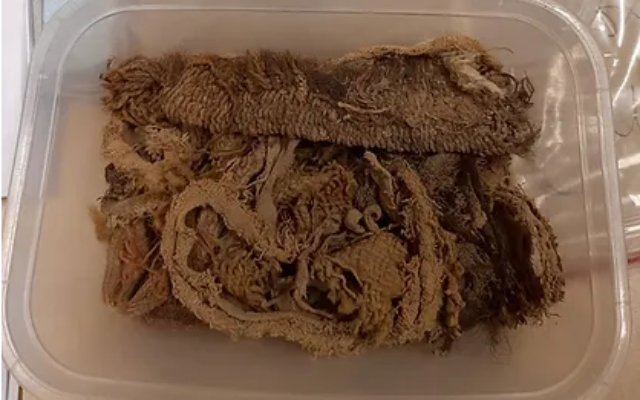

In a joint excavation sponsored by Germany and carried out by the University of Haifa, the University of Göttingen, and the Israel Antiquities Authority, large quantities of cotton and silk fabrics that likely originated in China, India and modern-day Sudan during the 8th century CE were uncovered in a massive garbage pit at the Nahal Omer site in the Arava Valley, according to a statement issued by the researchers on Wednesday.

“As far as textiles are concerned, Nahal Omer is the most important of all the ancient sites discovered to date in Israel,” the researchers said in the press release.

The findings have not been published in a scientific article yet, as the first season of the ongoing excavation was only completed two weeks ago, Bar-Oz told The Times of Israel. Nevertheless, researchers say they provide far-reaching implications for our understanding of ancient trade routes and, for the first time, the role this region played in the ancient world.

“The findings include a large proportion of imported items, including fabrics bearing typical Indian origin and silk items from China,” said Dr. Orit Shamir from the Israel Antiquities Authority, an expert on ancient textiles in Israel.

“This is the first time that these items dating back to this period have been found in Israel,” she said.

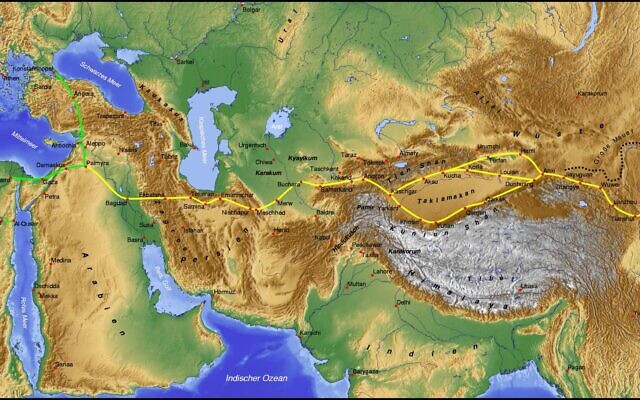

The Silk Road was a network of trade routes used to move exotic goods from China through India, Egypt, and the Middle East to Europe. Most routes were active between the second century CE and the mid-15th century. According to Bar-Oz, his team’s findings seem to provide the first evidence that there was also an Israeli route used by traveling international merchants.

“This route branched off from the traditional Silk Route that passed to the north of Israel, crossing the Arava and connecting to the main historical trade routes that crossed the country, as well as to the main ports of Gaza and Ashkelon that served as a major gateway to the Mediterranean world,” he explained.

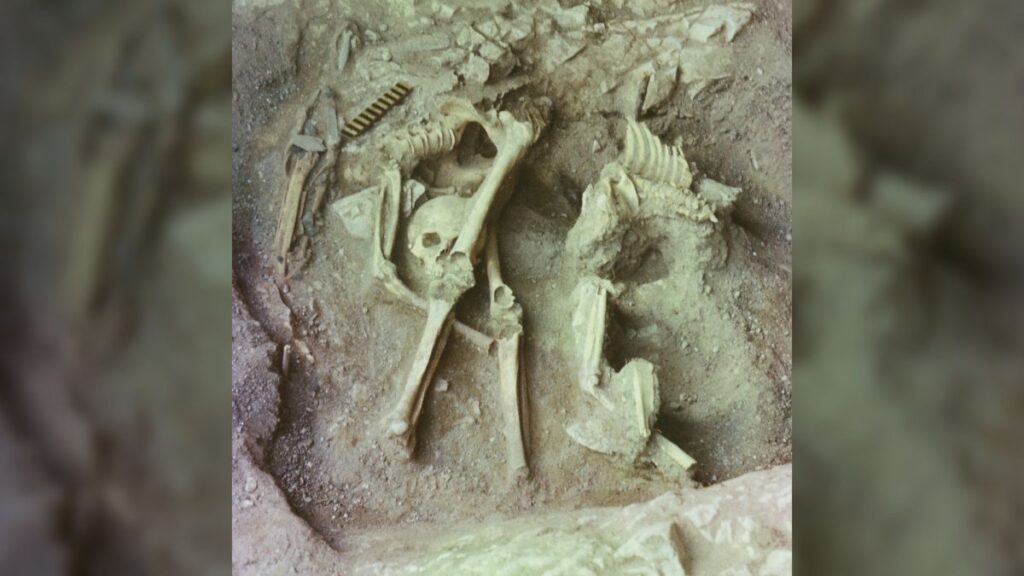

Analyzing ancient garbage

According to the archaeologists, their ongoing investigation is unique in that it explores changes in the Arava Valley over long periods of time by analyzing “accumulations of garbage at sites along the trading routes.”

By examining trash mounds at Nahal Omer, which dates to the seventh century CE — the beginning of the Islamic Era in the region — the researchers hope to learn about the everyday lives of traders passing through ancient Israel and to gain an idea of the products they were carrying.

Excavations will resume next summer, said Bar-Oz, and there will be at least two more seasons. Much further research will be carried out on the uncovered textiles, he noted.

Bar-Oz, who specializes in locating and analyzing deposits of trash on ancient trade routes, told The Times of Israel that others have carried out numerous archaeological excavations at Nahal Omer and the surrounding region before, but nobody thought to focus on garbage deposits and the valuable information they could provide.

“We started examining not the well or the fortress or the wall, but things in the perimeter,” he said,

Previous research and academic discussion about ancient trade relied mainly on historical accounts, often from people located far away, according to Bar-Oz.

“We discovered the trash mounds [at Nahal Omer] two years ago and started digging,” he said. “This was new.”

Archaeological remains that allow researchers to touch the material itself are rare but at Nahal Omer they were found in abundance.

“We dug holes five meters deep — imagine the volume of a Suzuki Alto made of garbage. Nearly all mounds we found included mainly organic material. The large volume of such material is the mind-blowing aspect of this excavation,” Bar-Oz said.

“The items we found allowed us to touch, see and measure them with molecular tools. It made it possible to track the production line of the goods that were moved along the trade route,” he added.

High demand

Analyzing their findings, researchers were surprised to find “a veritable treasure trove” that included fabrics, items of clothing, hygienic products, leather straps, belts, socks, shoe soles, and combs.

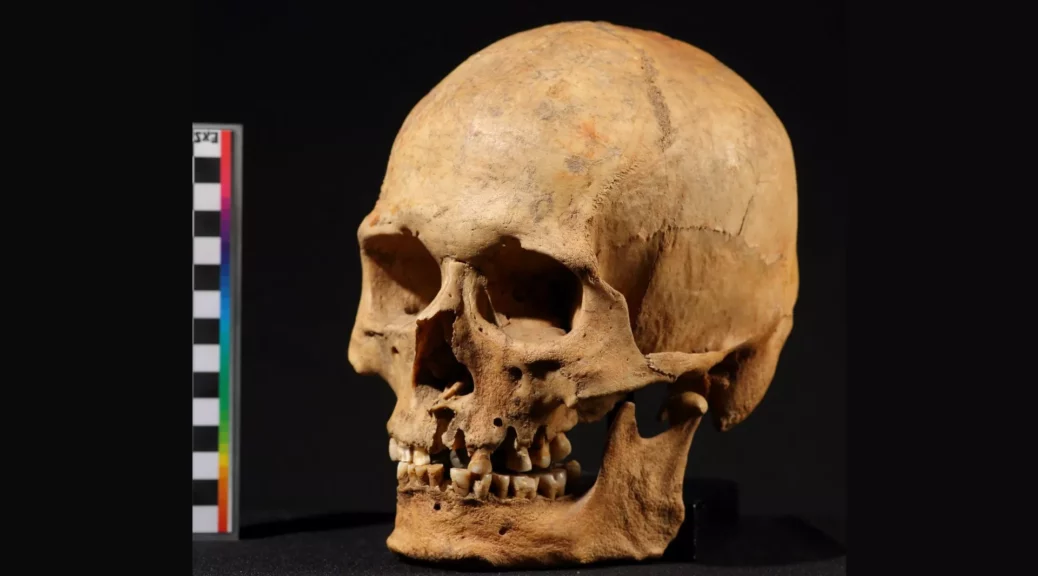

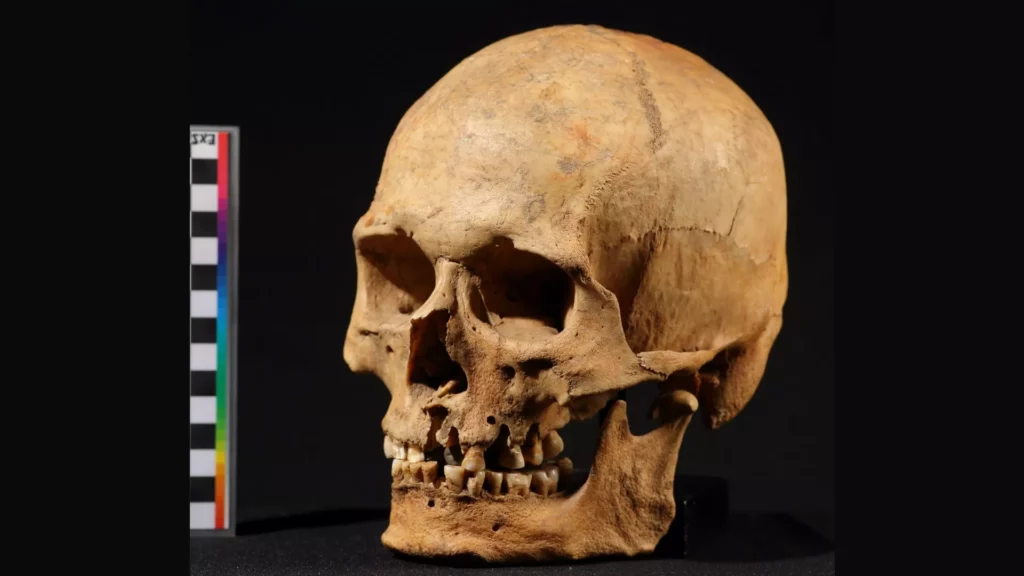

This wealth of organic material allows the researchers to precisely date the items to the 7th-8th centuries CE using carbon dating, a method that uses the properties of radiocarbon to determine the age of organic material.

This was made possible due to the dry conditions in Israel’s Negev desert. Materials that would usually disintegrate in humid climates were excellently preserved, researchers said.

One specific finding that excited researchers was fabrics bearing ikat design, a technique originating from Indonesia that includes tying the yarns before dyeing the warp or weft. Ikat fabrics have only been found at a small number of sites in the Middle East and researchers say these findings at Nahal Omer represent one of the earliest archaeologically documented occurrences of this type of textile. Another find included fabrics woven together in a complex process common in Iran and other parts of Central Asia.

“The variety and richness of the findings show that luxury goods from the East were in high demand at the time,” said the IAA’s Shamir.

“The findings from the excavation reflect unique contacts on a global level with sources of fabric manufacturing in the Far East. They provide us with new ways to track political, technological and social interactions that have been constantly reshaped by trade networks,” said Bar-Oz.

“We can now explore in more detail the long-distance movement of goods, geographic diffusion of people and ideas and connections along the roads and production centers. All these were, until now, historically and archaeologically invisible or incompletely recorded. Our new findings are an important step in that direction,” he concluded.

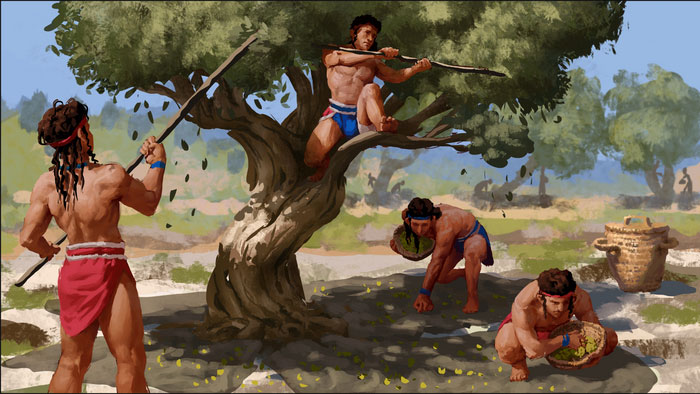

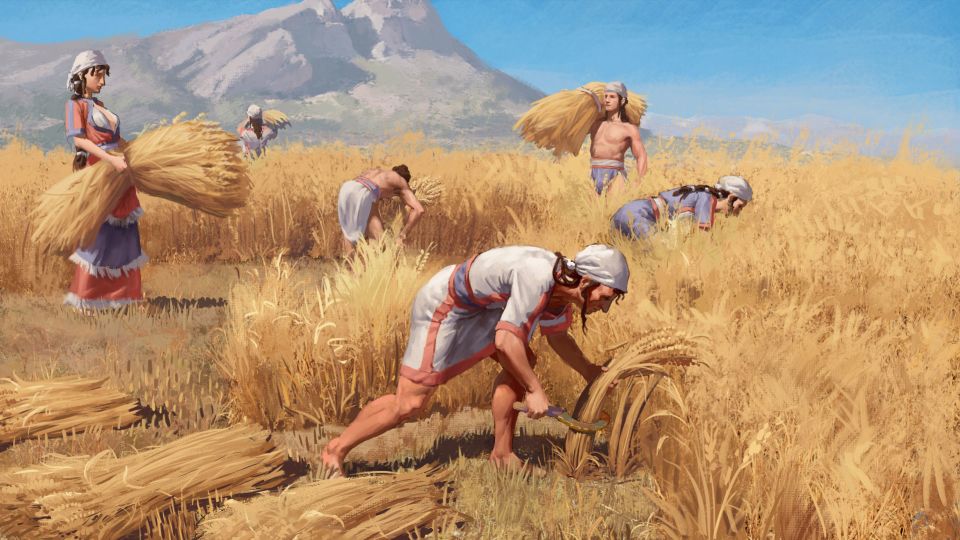

While the excavation at Nahal Omer provides an invaluable account of the vivid life in ancient Israel, its findings are not the oldest in the area. Last month, Israeli archaeologists from the University of Haifa discovered the earliest evidence of cotton in the ancient Near East during excavations at Tel Tsaf, a 7,000-year-old town in the Jordan Valley.

Tel Tsaf, located near Kibbutz Tirat Zvi, has in recent years provided a wealth of exciting discoveries, including the earliest example of social beer drinking and ritual food storage.