Rare ‘fish scale’ armour discovered in a Chinese tomb

About 2,500 years ago, a man in northwest China was buried with armour made of more than 5,000 leather scales, a military garment fashioned so intricately, its design looks like the overlapping scales of a fish, a new study finds.

The armour, which resembles an apron-like waistcoat, could be donned quickly without the help of another person. “It is a light, highly efficient one-size-fits-all defensive garment for soldiers of a mass army,” said study lead researcher Patrick Wertmann, a researcher at the Institute of Asian and Oriental Studies of the University of Zurich.

The team called it an early example of bionics or taking inspiration from nature for human technology. In this case, the fish-like overlapping leather scales “strengthen the human skin for better defence against the blow, stab and shot,” said study co-researcher Mayke Wagner, the scientific director of the Eurasia Department of the German Archaeological Institute and head of its Beijing office.

Researchers unearthed the leather garment at Yanghai cemetery, an archaeological site near the city of Turfan, which sits at the rim of the Taklamakan Desert. Local villagers discovered the ancient cemetery in the early 1970s. Since 2003, archaeologists have excavated more than 500 burials there, including the grave with the leather armour. Their findings show that ancient people used the cemetery continuously for nearly 1,400 years, from the 12th century B.C. to the second century A.D. While these people did not leave written records, ancient Chinese historians called the people of the Tarim Basin the Cheshi people, and noted that they lived in tents, practised agriculture, kept animals such as cattle and sheep and were proficient horse riders and archers, Wertmann said.

The armour is a rare find. Leather scale armour discovered in the ancient Egyptian tomb of King Tutankhamun, from the 14th century B.C., is the only other well-preserved ancient leather scale armour with a known provenance.

Another well-preserved leather scale armour, housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, dates from the eighth to the third century B.C., but its origin is unknown.

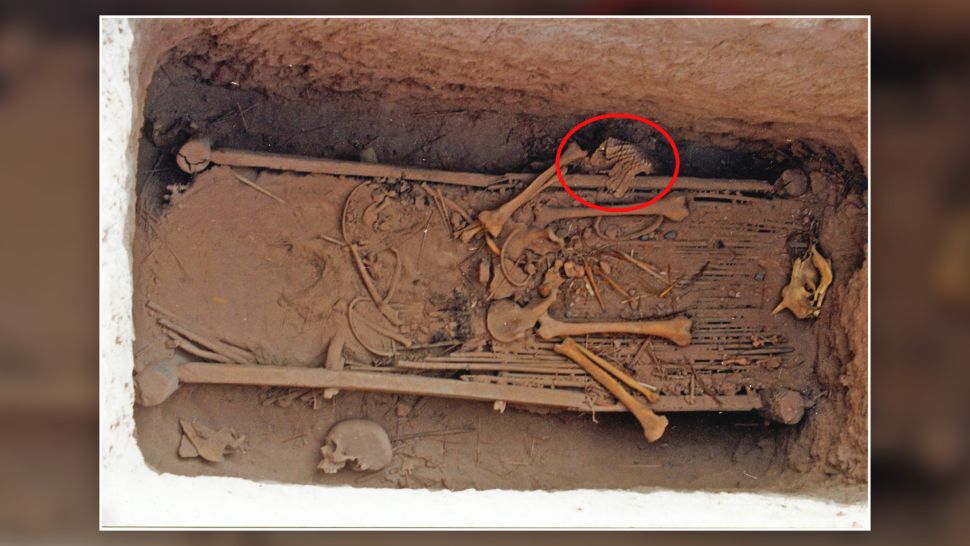

It was a “big surprise” to find the armour, Wagner told Live Science in an email. The researchers found the garment in the grave of a man who died at about age 30 and was buried with several artefacts, including pottery, two-horse cheekpieces made from horn and wood, and the skull of a sheep.

“At first glance, the dusty bundle of leather pieces [in the burial] … did not arouse much attention among the archaeologists,” Wagner said. “After all, the finds of ancient leather objects are quite common in the extremely dry climate of the Tarim Basin.”

A reconstruction of the body armour revealed that it sported 5,444 small leather scales and 140 larger scales, likely made of cow rawhide, that was “arranged in horizontal rows and connected by leather laces passing through the incisions,” Wagner said.

The different scaled rows overlap, a style that prompted the Greek historian Herodotus to call similarly fashioned armour, worn by fifth century B.C. Persian soldiers, just like “the scales of a fish,” Wagner noted.

A plant thorn stuck into the armour gave a radiocarbon date of 786 B.C to 543 B.C., the researchers found, indicating that it was older than the fish-like armour worn by the Persians. According to the team’s reconstruction, the armour would have weighed up to 11 pounds (5 kilograms).

Utterly unique

The discovery is one of a kind. “There is no other scale armour from this or an earlier period in China,” Wagner said. “In eastern China, armour fragments have been found, but of a different style.”

A deep dive into the history of scaled armour revealed that West Asian engineers developed scale armour to protect chariot drivers in about 1500 B.C. when chariotry became part of the military. After that, this style of armour spread northward and eastward to the Persians and Scythians and eventually to the Greeks. “But for the Greeks, it was always exotic; they preferred other types of armour,” Wertmann told Live Science.

Due to its local uniqueness, it appears that the newly described armour was not made in China, Wagner said. In fact, it looks like Neo-Assyrian military equipment from the seventh century B.C., which is seen in rock carvings, according to The British Museum.

“We suggest that this piece of leather scale armour was probably manufactured in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and possibly also the neighbouring regions,” Wertmann said. If this idea is correct, “then the Yanghai armour is one of the rare actual proofs of West-East technology transfer across the Eurasian continent during the first half of the first millennium B.C.E.,” the researchers wrote in the study.

How was it worn?

The armour mainly protects the front torso, hips, left side and lower back. “This design fits people of different statures because width and height can be adjusted by the thongs,” Wertmann said. Its left-side protection meant the wearer could easily move their right arm.

“It seems the perfect outfit for both mounted fighters and foot soldiers, who have to move rapidly and rely on their own strength,” he added. “The horse cheek pieces which were found in the burial may indicate that the tomb owner was indeed a horseman.”

However, how the armour ended up in the man’s burial “remains a riddle,” Wertmann said. “Whether the wearer of the Yanghai armour himself was a foreign soldier (a man from Turfan) in Assyrian service who was outfitted with Assyrian equipment and brought it home, or he captured the armour from someone else who was there, or whether he himself was an Assyrian or North Caucasian who had somehow ended up in Turfan is a matter of speculation. Everything is possible.”