Shattered Skeletons of Man and Dog From Eruption and Tsunami 3,600 Years Ago

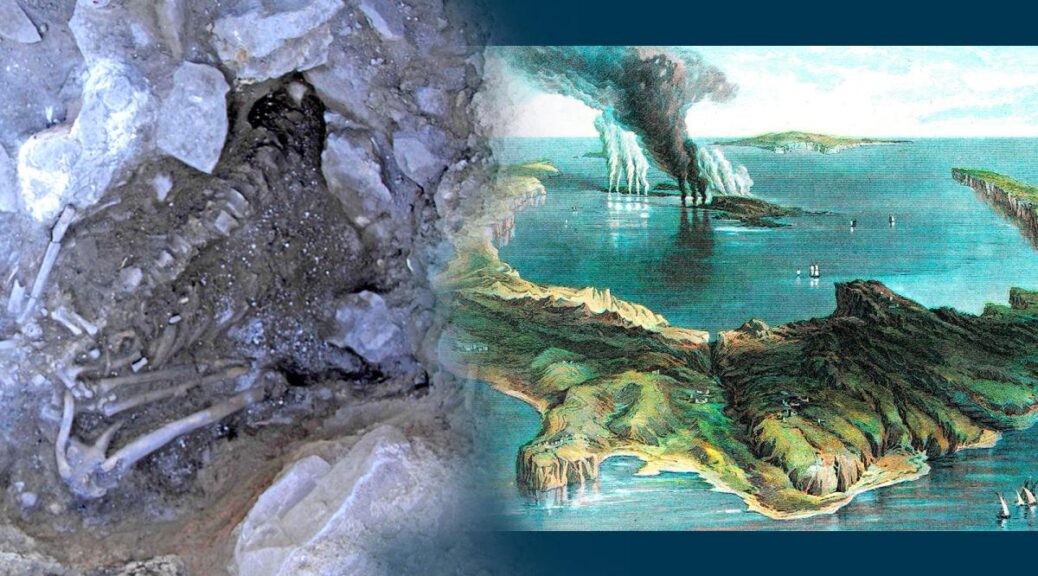

The remains of a young man and a dog who were killed by a tsunami triggered by the eruption of the Thera volcano 3,600 years ago have been unearthed in Turkey. Archaeologists found the pair of skeletons during excavations at Çeşme-Bağlararası, a Late Bronze Age site near Çeşme Bay, on Turkey’s western coastline.

Despite the eruption of Thera being one of the largest natural disasters in recorded history, this is the first time the remains of victims of the event have been unearthed.

Moreover, the presence of the tsunami deposits at Çeşme-Bağlararası show that large and destructive waves did arrive in the northern Aegean after Thera went up.

Previously, based on the evidence available, it had been assumed that this area of the Mediterranean only received ash fallout from the eruption of Thera.

Instead, it now appears that the Çeşme Bay area was struck by a sequence of tsunamis, devastating local settlements and leading to rescue efforts.

Thera — now a caldera at the centre of the Greek island of Santorini — is famous for how its tsunamis are thought to have ended the Minoan civilisation on nearby Crete.

Based on radiocarbon dating of the tsunami deposits at Çeşme-Bağlararası, the team believe that the volcano’s eruption occurred no earlier than 1612 BC.

The study was undertaken by archaeologist Vasıf Şahoğlu of the University of Ankara and his colleagues.

‘The Late Bronze Age Thera eruption was one of the largest natural disasters witnessed in human history,’ the researchers wrote in their paper.

‘Its impact, consequences, and timing have dominated the discourse of ancient Mediterranean studies for nearly a century.

‘Despite the eruption’s high intensity and tsunami-generating capabilities, few tsunami deposits [have been] reported.

‘In contrast, descriptions of pumice, ash, and tephra deposits are widely published.’

Amid stratified sediments at the Çeşme-Bağlararası site, the researchers found the remains of damaged walls — once part of a fortification of some kind — alongside layers of rubble and chaotic sediments characteristic of tsunami deposits.

Within these were two layers of volcanic ash, the second thicker than the first, and a bone-rich layer containing charcoal and other charred remains. According to the team, the deposits represent at least four consecutive tsunami inundations, each separate but nevertheless resulting from the eruption at Thera.

Tsunami deposits associated with the eruption are relatively rare — with three found near the northern coastline of Crete and another three along Turkey’s coast, albeit much further south than Çeşme-Bağlararası.

Traces of misshapen pits dug into the tsunami sediments at various places across the Çeşme-Bağlararası site represent, the researchers believe, an ‘effort to retrieve victims from the tsunami debris.’

‘The human skeleton was located about a meter below such a pit, suggesting that it was too deep to be found and retrieved and therefore (probably unknowingly) left behind,’ they added.

‘It is also in the lowest part of the deposit, characterized throughout the debris field by the largest and heaviest stones (some larger than 40 cm [16 inches] diameter), further complicating any retrieval effort.’

The young man’s skeleton — which shows the characteristic signatures of having been swept along by a debris flow — was found up against the most badly damaged portion of the fortification wall, which the team believe failed during the tsunami.

The full findings of the study were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.