Archaeologists find a gold “solar bowl” in a 3,000-year-old settlement in Austria

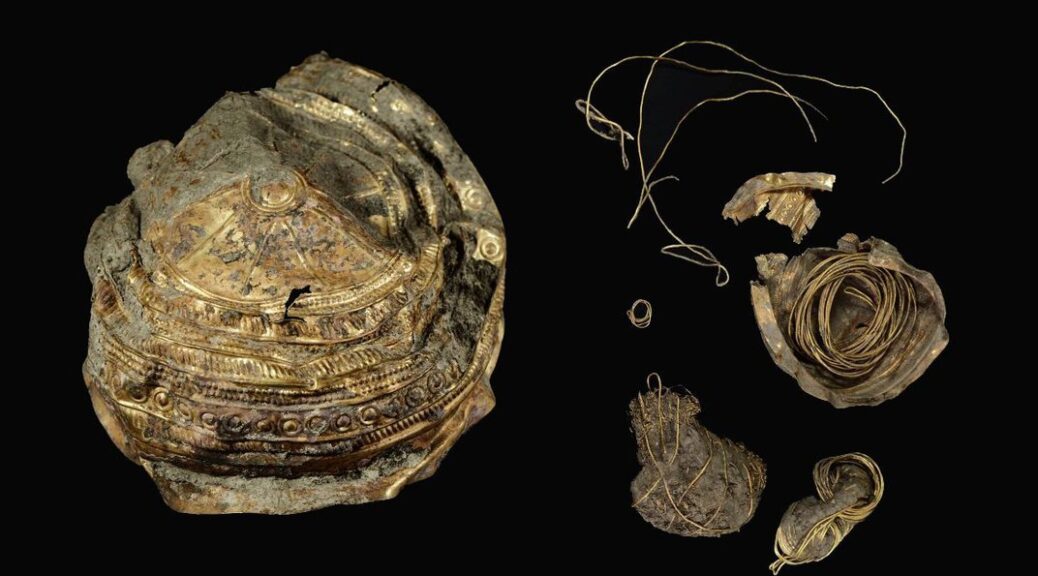

It was, in the words of archaeologist Michał Sip, the “discovery of a lifetime.” Unearthed ahead of construction of a railway station in Ebreichsdorf, just south of Vienna, the roughly 3,000-year-old golden bowl features a sun motif and is the first of its kind found in Austria, reports Szymon Zdziebijowski for the state-run Polish Press Agency (PAP).

Vessels of this kind have been found in other European countries, including Spain, France and Switzerland, says Sip, who is leading the excavation for Novetus, a German company that assists with archaeological digs. Only 30 similar bowls are known to exist, according to Heritage Daily.

Measuring about 8 inches long and 2 inches high, the Ebreichsdorf bowl is made of a thin metal consisting of 90 per cent gold, 5 per cent silver and 5 per cent copper.

“This is the [second] find of this type [discovered] to the east of the Alpine line,” Sip tells PAP, per Google Translate.

He adds, “Much more is known from the area of northern Germany, Scandinavia and Denmark because [this kind of pottery was] produced there.”

The golden vessel is linked to the Urnfield culture, a prehistoric society that spread across Europe beginning in the 12th century B.C.E., per Encyclopedia Britannica.

The group derived its name from the funerary ritual of placing ashes in urns and burying the containers in fields.

An image of the sun with rays emanating from it adorns the newly discovered bowl. Inside the vessel, archaeologists found two gold bracelets and coiled golden wires wrapped around now-decomposed fabric or leather.

“They were probably decorative scarves,” Sip tells PAP. He posits that the accessories were used during religious ceremonies honouring the sun.

Sip and his colleagues unearthed around 500 bronze objects, clay pottery and other artefacts at the Austrian site, which appears to have been a sizable prehistoric settlement. The team found the golden bowl in the shallow ground near the wall of a house last year.

“[T]he numerous and valuable finds in the form of bronze and gold objects are unique in this part of Europe, and so is the fact that the settlement in Ebreichsdorf … was so large,” Sip tells PAP.

Soon after the find’s discovery, the Austrian government stepped in to ensure the artefacts’ safety. The golden bowl will soon go on view at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

“The discovery of a treasure hidden 3,000 years ago was spectacular,” Christoph Bazil, president of the Austrian Federal Monuments Office, tells Remonews. “[We] immediately placed the richly decorated gold bowl, the gold spirals and the remnants of a gold woven fabric under protection due to their importance at the European level.

The Ebreichsdorf archaeological excavation goes down in history with this golden treasure.”

Speaking with Austrian broadcaster noe.ORF.at, Franz Bauer, director of ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG, which oversees the country’s rail transport, says the bowl’s presence suggests the region had “intensive trade relations” with other European settlements. It was likely made elsewhere and brought to Ebreichsdorf.

Though archaeologists found the artefacts in 2020, authorities decided to hold off on disclosing the news until a detailed analysis could be completed. Excavations will continue at the site for the next six months.