Deformed ‘alien’ skulls offer clues about life during the Roman Empire’s collapse

The multicultural change between local residents and migrant Romans is documented by researchers studying deformed skulls from an old cemetery in Hungary.

Mönzs-Icsei dülő cemetery, founded in 430 AD and abandoned in 470 AD, in the settlement of Mözs near Szekszárd in the Pannonia region of present-day Hungary, was created in the late Roman period at the beginnings of Europe’s Migration Period when the barbarian Huns invaded Central Europe forcing the Romans to abandon their Pannonian provinces and retreat from modern-day Western Hungary.

The site was recently excavated by a new study integrating experimental isotope analysis and biological anthropology, which determine that seeking refuge from the Huns, new foreign groups arrived in Pannonia and integrated with the remaining local Romanized population.

These migrant waves sparked a period of rapid-onset, and chaotic cultural transitions, and the deformed skeletons recovered from Mözs-Icsei dülő cemetery held important clues about life and death during this turbulent time.

The new paper was published April 29, 2020, in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Dr. Corina Knipper from the Curt-Engelhorn-Center for Archaeometry, Germany, István Koncz, Tivadar Vida from the Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary, and colleagues.

The authors first conducted an archaeological survey of the 5th-century cemetery, and then they combined isotope analysis with biological anthropology to interpret the burials.

What the pair of researchers found was a “remarkably diverse” ancient community consisting of two or three generations (96 burials total) of three distinctly different cultural groups.

The first was the founding, or local, group who were buried in brick-lined Roman-style graves, the second group comprised of 12 foreigners who arrived about a decade after the founders, and the third were a later culture, who blended Roman and various foreign traditions.

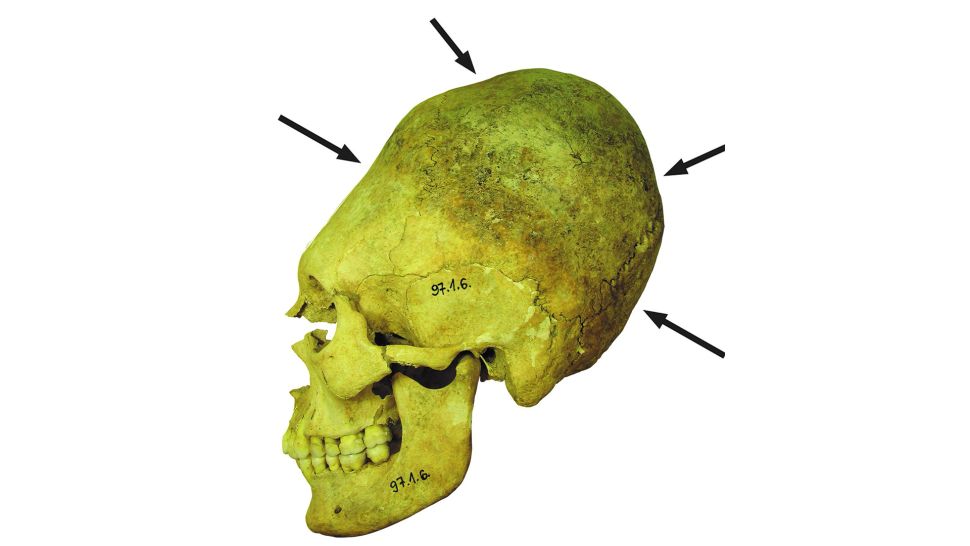

The researchers think that the second group of 12 foreigners most probably established the ritual burial tradition of burying the deceased with elaborate grave goods, and also the practice of “cranial deformation,” which was found in 51 skeletons of adult males, females, and children.

Artificial cranial deformation, or modification, is commonly called head flattening, or head binding. This ancient form of body alteration in which a human child’s skull is deformed with blocks of wood bound to the skull under a constant force, was practiced on every continent of the prehistoric world.

However, Mözs-Icsei dülő cemetery represents one of the largest concentrations of this ancient aesthetic cultural phenomenon in the region; a practice that was generally reserved for societal elites.

Buckle in, it’s time for the science bit: according to researcher Doug Dvoracek from the Centre of Applied Isotope Studies at the University of Georgia , who was not involved in the new study, strontium isotopic ratios are widely used as indicators of provenance, residential origins and migration patterns of ancestral humans, in an archaeological context, where it provides “links to the land where food was grown or grazed.”

The two researchers’ data showed the strontium isotope ratios measured on skeletons at the Mözs-Icsei dülő cemetery were “significantly more variable” than the prehistoric burials and animal remains excavated at other archaeological sites in the same geographic region in the Carpathian Basin.

In conclusion, the scientists say their isotopic analysis indicates most of Mözs’ adult population had lived elsewhere during their childhood and had migrated to Pannonia as teens and adults.

Moreover, carbon and nitrogen isotope data attest to what the scientists say were “remarkable contributions of millet” in the human diet.

Millets are a group of highly variable small-seeded grasses that were grown as cereal crops or grains for human food and fodder.

What ancient cultures who grew millets observed, but didn’t know why they had stronger bones, bigger muscles, tougher warriors and fitter farmers, because not only is millet gluten-free, but it also has high levels of protein, fiber, and antioxidants contents.

In the 5th century, the forested mountain ranges and resource-rich agricultural plains of what is today Hungary made this region a choice destination for fleeing Romans and other asylum seekers and refugees displaced by expanding Germanic armies.

And while archaeological and anthropological research in Hungary will continue, for now, the researchers have established that after the decline of the Roman Empire at least one community briefly emerged in Pannonia comprising local and Roman incomers who not only shared the same geographical space, but they blended and infused their burial rituals and traditions into a new multicultural system of internment.