In the frugal last meal of a man 2,400 years ago, scientists see signs of human sacrifice

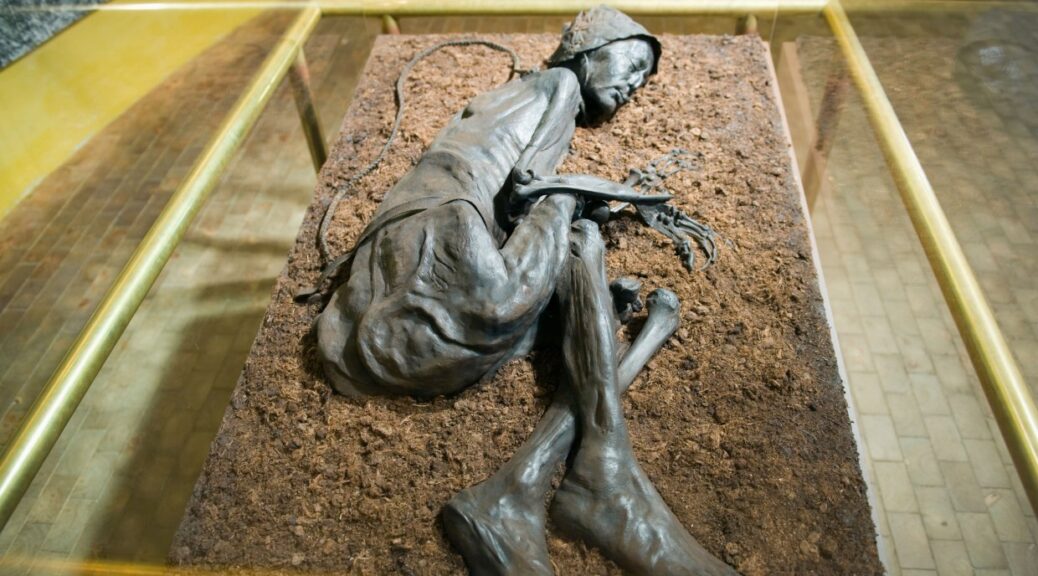

When the Tollund man was discovered in a bog in Denmark 71 years ago, he was so well preserved that his researchers thought he was the victim of a recent murder.

It took archaeologists to reveal that he was thrown into the bog almost 2,400 years ago and was first hanged – a braided animal skin noose was still around his neck. The careful arrangement of body and face – his closed eyes and weak smile – suggested that he may have been killed as a human sacrifice, rather than executed as a criminal.

The suggestion that Tollund’s man was killed as a human sacrifice has now been reinforced by a study of the condemned man’s last frugal meal, made from a detailed investigation of the contents of his digestive tract: a porridge of barley, flax and pale persicaria.

Pale persicaria seeds are the key to this Iron Age murder mystery, said archaeologist Nina Nielsen, head of research at the Danish Museum in Silkeborg and lead author of the study published Tuesday.

The plant grows wild among barley crops, but evidence from Iron Age grain storage shows that it was generally cleaned as a weed during threshing. This suggests that it was part of the “threshing waste” that was deliberately added to the porridge – possibly as part of a ritual meal for those condemned to die by human sacrifice.

“Was it just a regular meal? Or was the trash hype something you only included when people ate a ritual meal? Nielsen said. ” We do not know it. “

The contents of the preserved intestines of the Tollund man were examined soon after its discovery. But the new study refines that initial examination with much improved archaeological techniques and instruments.

“In 1950, they were only looking at the well-preserved kernels and seeds, not the very fine fraction of the material,” Nielsen said. “But now we have better microscopes, better ways of analyzing material and new techniques. So that means we could get more information out of it. “

In addition to revealing the clue of threshing waste added to his last meal, the researchers found that it was probably cooked in a clay pot – pieces of overcooked crust can be seen in the tracks – and that it had also eaten fish. They also found he was suffering from several parasitic infections when he died, including tapeworms – likely from a regular diet of undercooked meat and contaminated water, Nielsen said.

Tollund Man is one of dozens of Iron Age bog bodies around 2,500 to 1,500 years ago that have been discovered across northern Europe. They were mummified in peatlands by the low oxygen levels, low temperatures, and water made acidic by the layers of decaying vegetation, or peat, therein.

A few appear to have been victims of accidents, possibly people who drowned after falling into the water. But most, like the Tollund man, were killed and deliberately placed in the bogs, with their bodies and features carefully arranged. Archaeologists believe they were selected as human sacrifices, possibly to avert impending disaster like famine.

Miranda Aldhouse-Green, professor emeritus of history, archeology and religion at Cardiff University in the UK and author of the book ‘Bog Bodies Uncovered: Solving Europe’s Ancient Mystery’, said the seeds of pale persicaria and other traces of threshing waste in Tollund Man’s latest slurry are further evidence that he was sacrificed.

“It reinforces the idea that he was either humiliated by being given something disgusting and horrible to eat, or it actually reflected the fact that society was in a downward spiral where food was scarce,” she said. declared.

The idea that the victims of human sacrifices had somehow been “ashamed” before death was also reflected in their burials in bogs, instead of the usual burials in graves and dry graves, she said.

The preservative properties of peatlands were well known to people of the Iron Age – many archaeological objects from that era, including pieces of expensive pottery, were also deliberately deposited there – and it may be that the preservation of a bog body was intended to preserve it. to join his ancestors. The bogs were seen as gateways to another kingdom.

“If you put a body in the bog, it wouldn’t decompose – it would stay between the realms of the living and the dead,” Aldhouse-Green said.

There is evidence that threshing waste was added to the last meal of another Iron Age bog body found in Denmark in 1952, that of Grauballe Man, who was also said to have been killed as a human sacrifice. Although more than 100 bog bodies have been found, only 12 are well enough preserved that their last meals can be analyzed, Nielsen said, and she now hopes to seek further evidence of the ritual practice.

The Man from Tollund now occupies a display case in a special gallery in the Silkeborg Museum, where Nielsen can see him almost every day.

“You are face to face with a person from the past,” she said. “He’s 2,400 years old, it’s really amazing.