Tomb Saviors: Two Giants Found In Ancient Graveyard Could Have Been Body Guards

Giant statues crafted more than 3,000 years ago could have been guardians of an ancient graveyard, say experts. The mysterious Bronze Age giants were found at a necropolis near Mont’e Prama in Cabras, a small town in the western part of the island of Sardinia.

Dated to between the 11th and 8th centuries BC, these giants – or Kolossoi – are the oldest human-shaped sculptures found in the Mediterranean.

Experts say they are younger than ancient Egyptian statues but older than Greek kouroi statues dating from the 7th century BC.

The new finds will be added to discoveries first made in 1974. The more recent excavations recovered 5,000 pieces, which include 15 heads and 22 torsos. Fully rebuilt, the statues measure 2.5 meters tall – or just over 8 feet.

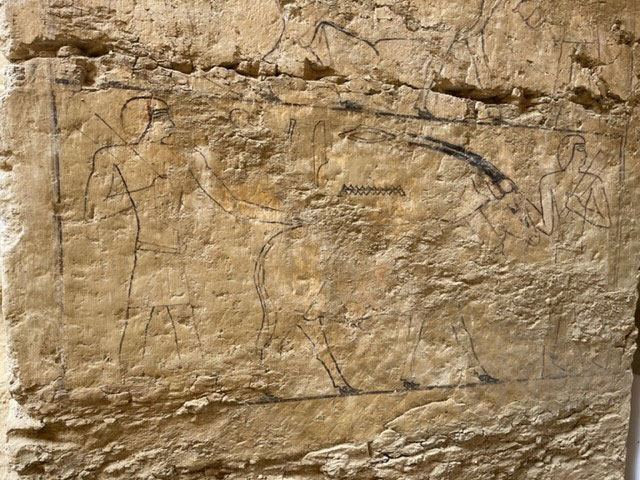

The figures and other sculptures were carved in native grainy limestone.

The giants resemble others recovered in 2014, known as “boxers” for the curved shields each bears on the left arm. Italy’s Minister of Culture Dario Franceschini said: “An exceptional discovery, which will be followed by others, which has no equal in the Mediterranean.”

Franceschini said of the statues: “Two new jewels are thus added to this statuary group with a mysterious charm, capable of attracting the attention of the whole world.”

Expert Alessandro Usai, who has been digging at the site since 2014, said: “In particular, the two torsos found with the elongated shield that takes on a slightly enveloping shape with respect to the left arm and which flattens on the belly bring the findings back to the category of boxers.”

According to archaeologist Monica Stochino, who participated in the dig: “While the small and medium-sized fragments are brought to light daily, documented in situ on the ground and recovered, the two large and heavy blocks of the torsos will need time to be freed from the earth around them…”

She added that work remains to completely excavate the site, remove the artefacts, and ultimately exhibit them. The limestone used by the ancients was easily carved, but fragile, thus making transportation and restoration difficult. The Nuragic civilization of Sardinia lasted from about the 18th century BC until Roman colonization in 238 BC.

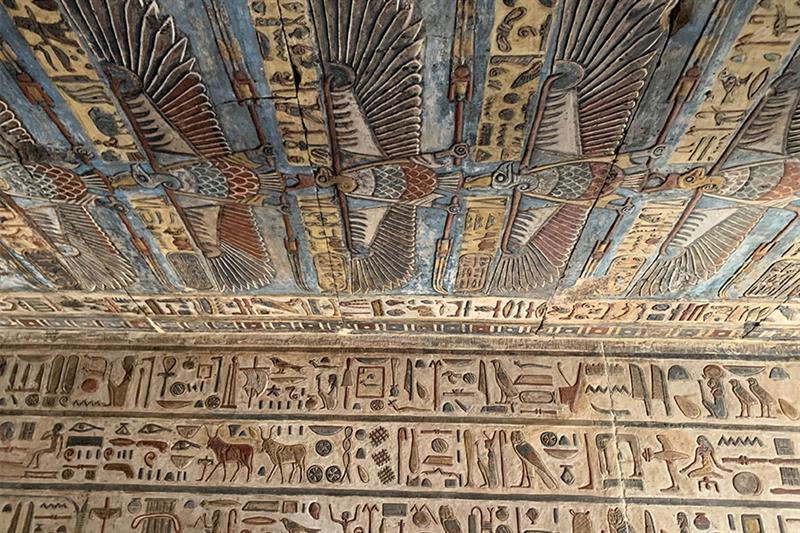

The name Nuragic refers to Sardinia’s most characteristic monument, the 7,000 circular stone “nuraghe” forts built across the island, which bear silent witness to the ancient people who left no written records.

The ancient Greeks and Romans later wrote mythical accounts about the Nuragic people. Nuragic people may have navigated elsewhere in the Mediterranean, ranging from what is now modern-day Spain and its islands, to mainland Italy, Crete, and even Israel. The Carthaginians from North Africa also lived on the island and may have dominated the Nuragic people. Their tombs and monuments include standing stones resembling Britain’s Stonehenge, as well as megalithic tombs known as dolmens, which are also found elsewhere in Europe.

Mont’e Prama, where the new statues were found, is a necropolis or cemetery dating from the end of the 9th century to the first half of the 8th century that features a funerary road. It shows three phases: the first consists of simple tombs where bodies were inhumed; a second featuring grouped tombs each covered by rough stone slabs; and a third in which perfectly-aligned tombs are covered with square slabs.

The giant statues were shattered in ancient times and then deposited on top of or next to the tombs. While the stone was quarried nearby, it is not known where the statues were originally erected before ending up at the necropolis. Some experts believe they were used to mark off a sacred space, while others assert they were placed on slabs covering the tombs.

Opinions also differ over their destruction, with some experts asserting it came because of internal strife among the Nuragic peoples, while others blame Phoenicians of nearby Tharros on the Sinis peninsula.

Yet another theory proposes that the statues were demolished by Carthaginians, during the much later second half of the 4th century BC.

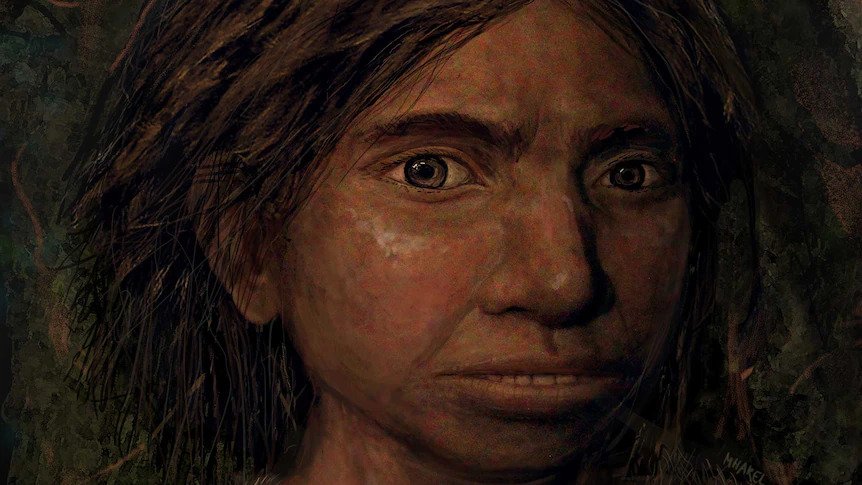

The statues appear to be warriors or “boxers,” and may represent Nuragic ancestors, gods, or mythical heroes, while Mont’e Prama may have been a heroon or hero-shrine where they were worshipped.

As evidence that it was a place for honouring heroes, Usai noted that among the 170 tombs, there were none with the remains of children or elderly people. There were very few women buried at the necropolis, which appeared to be almost exclusively reserved for young men. Stochino explained that the research addressed two main objectives: “To confirm the extension of the monumental arrangement of the area with the definition of the funerary road and the creation of the sculptural complex made up of statues, models of nuraghe and betyls.”

According to the experts, the model nuraghe may have represented community identity or solidarity. Betyls or baetylus are sacred stones that some ancient cultures believed either gave access to their gods or were actually endowed with life. The word comes from the Semitic ‘bet el’, or ‘house of the god’, in much the same way as the biblical Bethel does.

As to the identity of the giants, and their purpose and fragmentation, Usai said that he leans to the conclusion that the statues were victims of a “natural” destruction, even while he granted that further investigation based on data may eventually uncover the mystery.