Possible Neanderthal Hunting Tactic Explored

Juan Negro crouched in the shadows just outside a cave, wearing his headlamp. For a brief moment, he wasn’t an ornithologist at the Spanish National Research Council’s Doñana Biological Station in Seville. He was a Neandertal, intent on catching dinner. As he waited in the cold, dark hours of the night, crowlike birds called choughs entered the cave.

The “Neandertal” then stealthily snuck in and began the hunt.

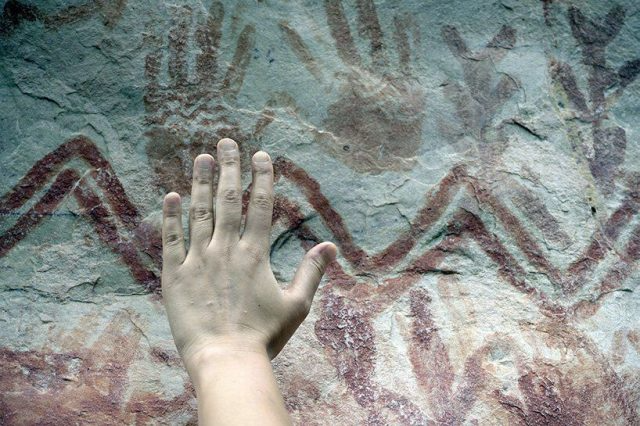

This idea to role-play started with butchered bird bones. Piles of ancient tool- and tooth-nicked choughs bones have been found in the same caves that Neandertals frequented, evidence suggesting that the ancient hominids chowed down on the birds. But catching choughs is tricky.

During the day, they fly far to feed on invertebrates, seeds and fruits. At night though, their behaviour practically turns them into sitting ducks. The birds roost in groups and often return to the same spot, even if they’ve been disturbed or preyed on there before.

So the question was, how might Neandertals have managed to catch these avian prey?

To find out, Negro and his colleagues decided to act like, well, Neandertals. Wielding bare hands along with butterfly nets and lamps — a proxy for nets and fire that Neandertals may have had at hand— teams of two to 10 researchers silently snuck into caves and other spots across Spain, where the birds roost to see how many choughs they could catch.

Using flashes of light from flashlights to resemble fire, the “Neandertals” dazzled and confused the choughs. The birds typically fled into dead-end areas of the caves, where they could be easily caught, often bare-handed. Hunting expeditions at 70 sites snared more than 5,500 birds in all, the researchers report September 9 in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.

The birds were then released unharmed. It was “the most exciting piece of research” Negro says he’s ever done.

The results demonstrate that through teamwork, choughs can be captured without fancy tools at night and offer a likely way that Neandertals could have captured choughs. But actual Neandertal bird-catching behaviour remains unknown. If this is in fact how Neandertals hunted, it adds to claims that their behaviour and ability to think strategically is more sophisticated than they are often given credit for.

“The regular catchment of choughs by Neandertals implies a deep knowledge of the ecology of this species, a previous planning for its obtaining, including procurement techniques, and the ability to plan and anticipate dietary needs for the future,” says Ruth Blasco.

A taphonomist at the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution in Tarragona, Spain, Blasco is an expert in the Neandertal diet.

Such role-playing, she notes, is “commonly used by scholars as valid analogies to infer processes that happened in the past.” For instance, reenactments with replicas of wooden spears have suggested that Neandertals could have hurled the weapons to hunt prey at a distance.

The researchers re-creating chough hunts used butterfly nets to catch birds fleeing sites with narrow entrances, as well as bigger nets partially covering larger openings. But “the easiest thing was to grab the birds by hand,” Negro says.

“You have to be intelligent to capture these animals, to process them, to roast and eat them,” he notes. Previous studies have shown that Neandertals may have been similarly adept at foraging for seafood. “We tend to think that [Neandertals] were brutes with no intelligence,” Negro says, “but in fact, the evidence is accumulating that they were very close to Homo sapiens.”