Archaeologists uncover oldest known projectile points in the Americas

Oregon State University archaeologists have uncovered projectile points in Idaho that are thousands of years older than any previously found in the Americas, helping to fill in the history of how early humans crafted and used stone weapons.

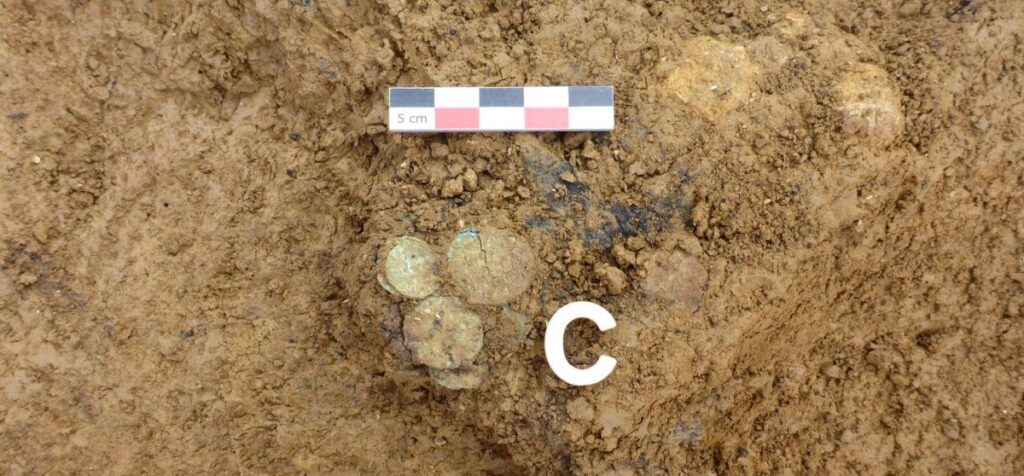

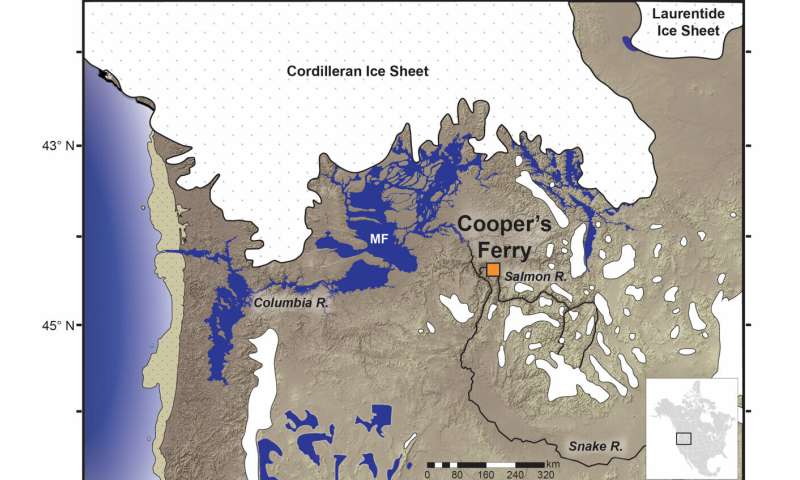

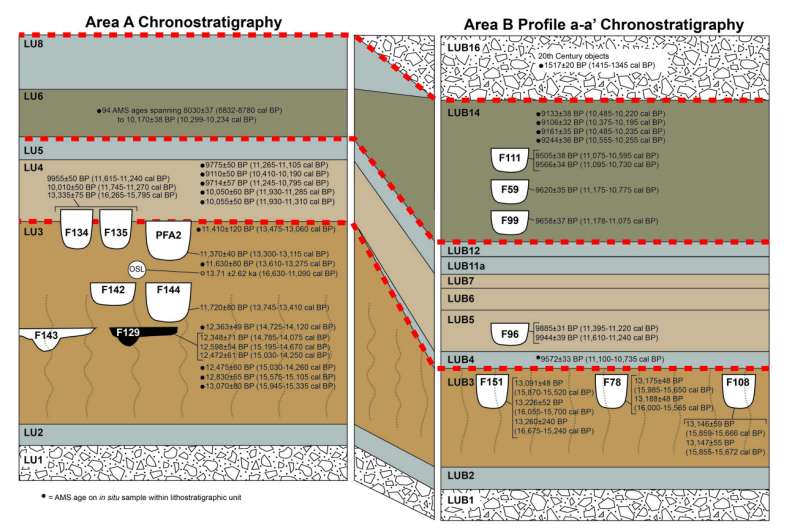

The 13 full and fragmentary projectile points, razor sharp and ranging from about half an inch to 2 inches long, are from roughly 15,700 years ago, according to carbon-14 dating. That’s about 3,000 years older than the Clovis fluted points found throughout North America, and 2,300 years older than the points previously found at the same Cooper’s Ferry site along the Salmon River in present-day Idaho.

The findings were published today in the journal Science Advances.

“From a scientific point of view, these discoveries add very important details about what the archaeological record of the earliest peoples of the Americas looks like,” said Loren Davis, an anthropology professor at OSU and head of the group that found the points. “It’s one thing to say, ‘We think that people were here in the Americas 16,000 years ago’; it’s another thing to measure it by finding well-made artifacts they left behind.”

Previously, Davis and other researchers working the Cooper’s Ferry site had found simple flakes and pieces of bone that indicated human presence about 16,000 years ago. But the discovery of projectile points reveals new insights into the way the first Americans expressed complex thoughts through technology at that time, Davis said.

The Salmon River site where the points were found is on traditional Nez Perce land, known to the tribe as the ancient village of Nipéhe. The land is currently held in public ownership by the federal Bureau of Land Management.

The points are revelatory not just in their age, but in their similarity to projectile points found in Hokkaido, Japan, dating to 16,000–20,000 years ago, Davis said. Their presence in Idaho adds more detail to the hypothesis that there are early genetic and cultural connections between the ice age peoples of Northeast Asia and North America.

“The earliest peoples of North America possessed cultural knowledge that they used to survive and thrive over time. Some of this knowledge can be seen in the way people made stone tools, such as the projectile points found at the Cooper’s Ferry site,” Davis said. “By comparing these points with other sites of the same age and older, we can infer the spatial extents of social networks where this technological knowledge was shared between peoples.”

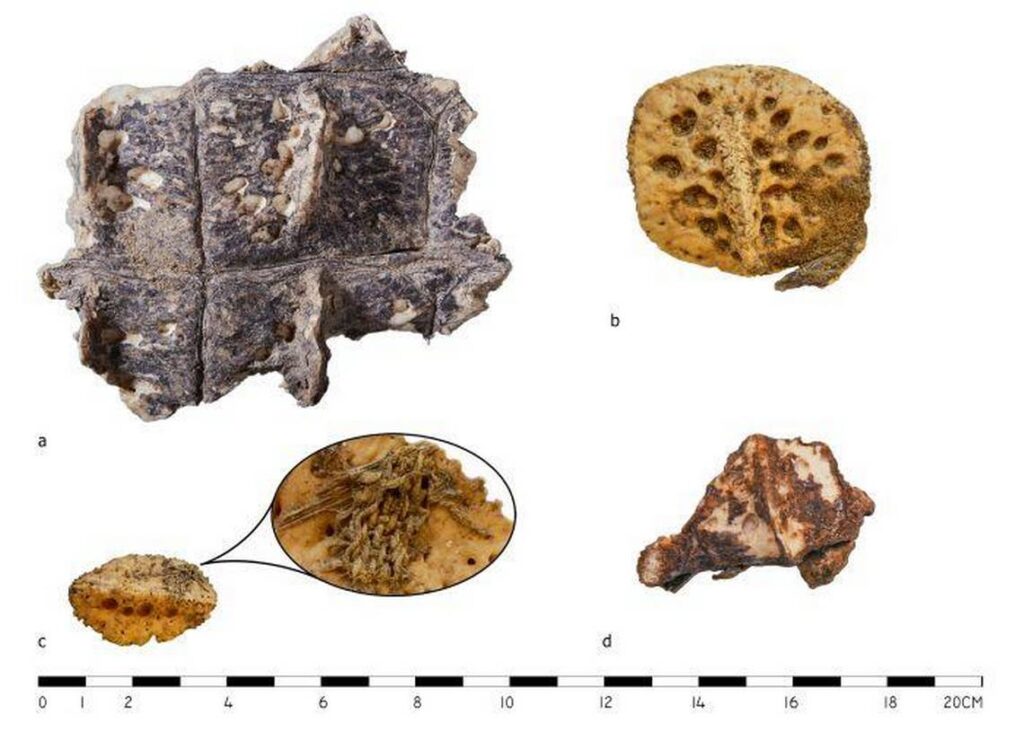

These slender projectile points are characterized by two distinct ends, one sharpened and one stemmed, as well as a symmetrical beveled shape if looked at head-on. They were likely attached to darts, rather than arrows or spears, and despite the small size, they were deadly weapons, Davis said.

“There’s an assumption that early projectile points had to be big to kill large game; however, smaller projectile points mounted on darts will penetrate deeply and cause tremendous internal damage,” he said. “You can hunt any animal we know about with weapons like these.”

These discoveries add to the emerging picture of early human life in the Pacific Northwest, Davis said. “Finding a site where people made pits and stored complete and broken projectile points nearly 16,000 years ago gives us valuable details about the lives of our region’s earliest inhabitants.”

The newly discovered pits are part of the larger Cooper’s Ferry record, where Davis and colleagues have previously reported a 14,200-year-old fire pit and a food-processing area containing the remains of an extinct horse. All told, they found and mapped more than 65,000 items, recording their locations to the millimeter for precise documentation.

The projectile points were uncovered over multiple summers between 2012 and 2017, with work supported by a partnership held between OSU and the BLM. All excavation work has been completed and the site is now covered. The BLM installed interpretive panels and a kiosk at the site to describe the work.

Davis has been studying the Cooper’s Ferry site since the 1990s when he was an archaeologist with the BLM. Now, he partners with the BLM to bring undergraduate and graduate students from OSU to work the site in the summer.

The team also works closely with the Nez Perce tribe to provide field opportunities for tribal youth and to communicate all findings.