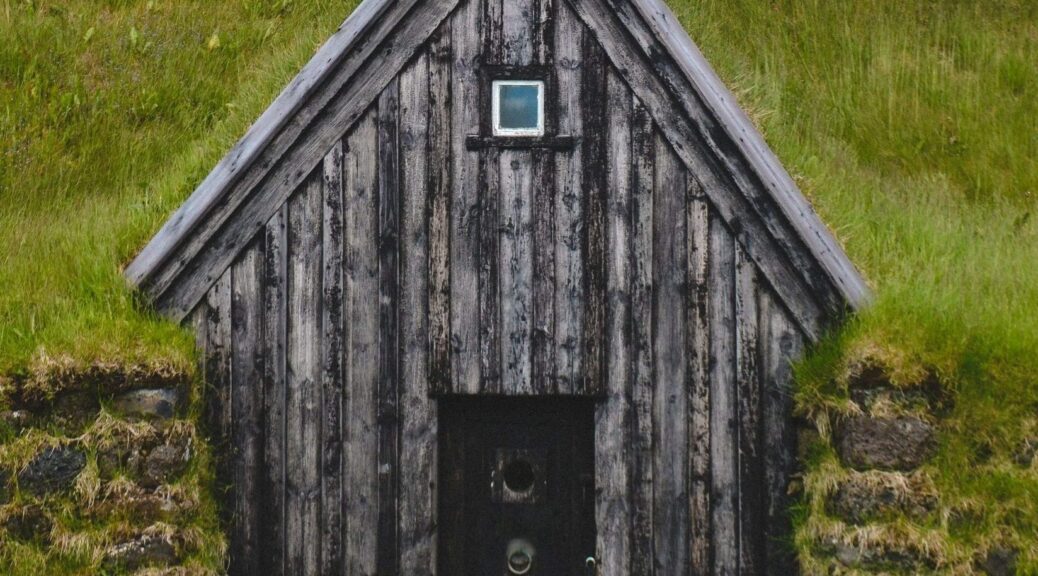

The Unique Architectural Heritage Of Icelandic Turf Houses that Hidden In The Landscape

Memorable, popular, and rumored to be the inspiration for Tolkien’s hobbit holes, turf houses are a rare form of home for the people who live in difficult climates.

For millennia, they have existed, and although layouts and materials may have changed, the basic format remains the same wood and stone frames surrounded by the Icelandic landscape’s most plentiful material: turf. In Iceland, where turf houses were the most common housing as late as the 1960s, the structures were practical and well-suited for the difficult weather and lack of timber.

The people responsible for bringing the knowledge of turf houses were the very first settlers and themselves from another cold, difficult climate – the Vikings.

When the Vikings arrived in Iceland in 874 AD, it wasn’t as barren as it appears today – in fact, 25-40% of the island was covered in forest, mainly birch trees, though they were on the short side due to lack of light and low temperatures.

But the new inhabitants cleared the forests for sheep grazing, agriculture, shelter, and firewood. Tree regeneration was inhibited by all the grazing and thus, the Vikings deforested Iceland. So where did they get the wood for their houses after they used up the forest? Driftwood and shipwrecks made up the deficit.

The Vikings built communal longhouses, often sharing one large room with dozens of people and occasionally, animals. Body heat was a very important tool for not freezing to death during the long dark winter, so inhabitants slept all in the same room with two or more per bed.

Turf longhouses varied in size depending on the wealth of the farmer or clan, and occasionally outbuildings like sheds and privies were also built.

The building method is genius.

First, a hole was dug a few feet down to where the ground doesn’t freeze. Then a stone footprint was laid using the flattest stones possible – this kept the wood from touching the damp ground and helped prevent rot.

A wooden frame was then erected on top of the stone footprint; the posts and beams were held together using notches and pegs, and a mat of small branches was laid over the roof beams to create airflow between the beams and the turf.

The turf was cut directly out of the ground using special tools and laid out to dry; then the turf “bricks” – held together by the root mass of the plants therein – were laid in two courses around the wood frame, with dirt and gravel compacted between the layers.

Turf bricks also covered the roof at a steep angle to facilitate water runoff. The resulting walls were extremely thick and provided excellent insulation and surprising water-tightness.

Viking houses included some very interesting features, like elaborate carved front doors with complex locks and holes for shooting arrows at attackers, and a sleeping closet for the master of the house and his wife that locked from the inside for extra protection against invaders.

Archaeological evidence suggests that more than the longhouse was communal – the turf outhouses featured group seating!

While the Viking turf houses undoubtedly fared well against Iceland’s notorious cold, damp, and dark weather, they did have some downsides.

Mice and lice often lived in the turf, and very bad storms could sometimes peel up the roofs. Turf houses also required a lot of maintenance, and depending on the severity of the winter needed to be re-turfed every 20 or so years.

By the 14th century, Viking style longhouses had given way to smaller, specialized buildings that were connected by tunnels to conserve heat. By the late 18th century, the burstabær style was the most popular, introducing wooden ends, or a wooden face with the back built into the side of a hill.

Many houses in this style still stand and have become the iconic Icelandic turf house. They remained the most common form of housing in Iceland until the 20th century when urbanization and modernization took the country by storm. Within 30 years, Icelanders had made the change to modern houses and city living, and the last full-time residents of turf houses moved out in the 1960s.

Today you can visit several turf houses, most of which have been restored and incorporated into the National Museum of Iceland, though some families have privately restored their ancestral homes.

Once a common skill, knowledge of turf house construction is now relegated to a handful of specialized craftsmen doing restoration and educational work.

But the influence of turf houses lives on: architecture firms in Iceland and abroad are rediscovering the appeal of the original “green” buildings, with their insulating properties and use of local materials. Besides being strong and practical, turf houses are cute – especially when the roofs are in bloom.