A 9,000-year-old head with amputated hands laid over could be the oldest ritual beheading in the Americas

The Amazon rain forest has long inspired gruesome stories of ritualistic violence from 19th-century tales of tribes searching for “trophy heads” to Hollywood films such as Mel Gibson’s Apocalypto.

But a much longer history than commonly believed can be portrayed of civilizations such as the Incas, Nazcas, and the Wari cultures making human sacrifices in South America may have a much longer tradition than previously thought.

Recent research, reported in PLOS One, records the discovery of a 9,000-year-old case of ritualized human decapitation that seems to be the oldest in the Americas by some margin.

Execution or burial?

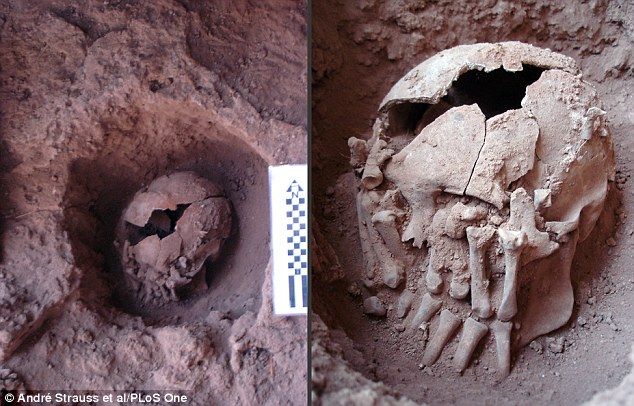

The researchers found the remains of the beheaded young man from a rock shelter in Lapa do Santo, East-Central Brazil. Quite astonishingly the decapitated remains date to between 9,100 and 9,400 years ago.

The decapitated skull was found with an amputated right hand laid over the left side of the face, with fingers pointing to the chin. It also had an amputated left hand laid over the right side of the face with fingers pointing to the forehead, making it highly ritualistic and extremely unusual.

However, the process of extracting the body parts from the victim seems straight out of a horror movie. The man was decapitated by blows from a sharp instrument to the neck, but there was also evidence that the head was distorted and twisted in places, suggesting there was difficulty getting the head off the body.

Furthermore, the cuts left on the bones were signs that the flesh had been removed from the head prior to it being buried. However, there’s no evidence to suggest decapitation was the cause of death.

The decapitation is reminiscent of Neolithic skull cults from the Middle East, which often buried their deceased under the floors of their homes – sometimes with the skull removed, plastered, and painted.

The placement of the hands is also similar to partial coverage of facial gestures that we see in different cultural settings today (such as signs of tiredness, shock, horror, etc).

This ritualistic behavior may seem barbaric to us today but it is becoming clearer that during the Neolithic period decapitations, skull cults, and ancestor worship were an important cultural practice. Excavations of neolithic sites in the Middle East have uncovered ancestors that had their fleshed removed in a similar way before being buried in the houses of their relatives.

The rituals undoubtedly involved many of the community to honour their ancestors and may be similar to what has been discovered at Lapa do Santo.

Local but unusual man

The researchers also undertook a number of scientific analyses to find out more about the individual. One of these was to analyze the teeth for isotopes of strontium, which is taken up in the human body through food and water.

The analysis of the tooth enamel, which is formed during childhood can be compared to the isotope signatures in the local geology. This can tell whether or not the individual was related to the place they were buried.

The analysis showed that the man was clearly associated with his place of burial. This implies he was a local man who grew up in the area and not a captured trophy from a warring faction.

But perhaps most intriguingly, they took measurements of the skull and compared it to measurements of other skeletons, including ones excavated at the same site. In this case, the young man’s head was a little bit of an outlier on the overall size of the skull, being slightly larger. Did he look different from the other men? Was he somehow distinctive? The remarkable evidence from this site suggests he was unique to their community but living with them and perhaps chosen for this reason?

This forensic approach to understanding archaeological remains is now shedding light on how much information can be gleaned from these deposits and the value of careful and meticulous work.

More broadly, this is one of many revelations that are starting to appear regarding South American archaeology ranging from evidence of early extensive burning of the landscape 9,500 years ago, through to large-scale deforestation and the production of glyphs by pre-European culture.

It remains to be seen how many more discoveries like this will be made in the future but there is one clear message, losing your head in South America is not a new phenomenon!